Doing the People’s Business in a Pandemic

In 2016, I worked on a study of the public procurement workforce. These are the people entrusted with spending our more than $2 trillion of tax revenue on goods and services for public use. At the time of that study, this critical segment of the public workforce was largely out of the public eye. Most of the public servants we interviewed were frustrated that public procurement received so little attention relative to its goliath scale and its mission-critical nature. In fact, we were obliged to begin the final report with a section entitled “Why Should the Public Care about Procurement?”

Today, as we battle against COVID-19, it is starkly apparent how much of the government’s response to the historic crisis is centered on thousands of procurement decisions. We have watched different levels of government engage in brutal bidding wars to acquire personal protective equipment and swab tests, driving up costs and undermining coordination. We discovered that one-fifth of the nation’s ventilator stockpile was unusable because of a lapsed maintenance contract. We have seen desperate governments send huge sums of money to dubious suppliers of critical equipment only to discover that the companies were little more than scams.

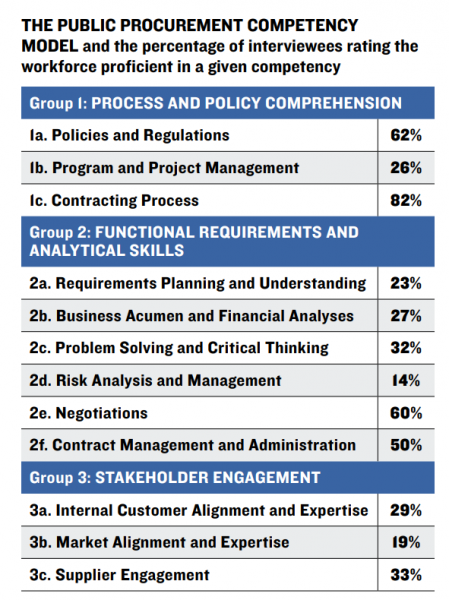

The COVID crisis is exposing the continued relevance of the issues that we explored in the Alliance’s 2016 study, “Doing the People’s Business.” Back then, we developed a 12-item competency model and interviewed 43 senior leaders in the world of public procurement—contracting officers at all levels of government, scholars, thought leaders, and vendors—to assess the existing public procurement workforce against the model. The results were sobering. Our respondents graded the workforce as broadly proficient in only 4 of the 12 competencies. Stark weaknesses in risk management, supplier engagement, and project management are especially resonant with the headlines.

Our respondents did not place blame primarily on frontline contracting officers as the primary cause of the many weaknesses in the system. Rather, they pointed to a system rife with burdensome reporting requirements, excessive fear of complaints from vendors and elected officials, and a failure of agency leadership to engage the workforce as a strategic asset focused on mission, rather than on minutiae. Over time, these systemic shortcomings have pushed many great public servants to take their valuable knowledge to higher-paying jobs in industry, further hobbling those who remained.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a bright light on the aspects of government upon which we so desperately depend. The procurement space is no exception. And our research confirms there are ample opportunities for needed and meaningful reform:

- Clarify and elevate the role of public procurement offices within agencies, to ensure that the people tasked with execution and implementation have full visibility and can help shape strategic choices.

- Invest in workforce capacity through training and technology modernization.

- Assess the costs of cumbersome regulations and reporting requirements, which can often paralyze workforces, distract from mission, and advantage well-connected vendors over new entrants.

- Get serious about risk management. The goods and services that governments acquire are critical, and supply chains can be unreliable in times of crisis. Building some slack capacity and inventory into the system to prepare for the unexpected is always a good investment.

Between crises, we too often treat the public servants who make government work as an afterthought or, worse, as an obstacle, rather than a national asset. First rate education for rising leaders, robust pipelines into public careers, and appropriate regard for the vocation of public service is what animates us and inspires our work at the Volcker Alliance. The need for each of these has been laid bare by COVID-19 and it is clear we must begin now to act together to address the barriers to excellence in government performance. Let’s not forget the public procurement workforce as we do so.