Ruminations on Inflation

Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Volcker Alliance FY2020 State Fiscal Conference

Atlanta, Georgia

July 11, 2019

In a speech at the Volcker Alliance's FY2020 State Fiscal Conference, Atlanta Fed president and CEO Raphael Bostic shares his thoughts on inflation, inflation measures, and monetary policy. Bostic explains that, to the extent that there is concern about the FOMC's price stability mandate of two percent inflation, it is not that inflation is too high, but that it may be too low. However, Bostic's reading on inflation is that the best measures suggest it is close to target and not materially trending away from it. What's more, he believes inflation expectations are not diverging from target, either. Bostic says the snapshot of the economy is a "keeper," and the policy settings needed to sustain this picture are what he and the FOMC will be wrestling with. Bostic will be going into the FOMC meeting with an open mind but feels we are in a good position.

Thank you, Chris. I guess you're assured a kind introduction when it comes from someone who works for you.

Thank you all for inviting me to speak. And thanks to the Volcker Alliance for the important work you do. Let me extend a special welcome to your president, Thomas Ross; to my predecessor, Dennis Lockhart; to Mayor Shirley Franklin; and to all of our distinguished guests.

Today, I'd like to discuss a topic that I hope will provide context for your work on fiscal concerns—inflation.

I must confess I'm feeling professorial, and there is a lot of material to cover in the next twnety minutes, so let's get right to it.

Please keep in mind that these thoughts are strictly my own. I do not speak for my colleagues at the Atlanta Fed or for the Federal Open Market Committee, the FOMC.

The macroeconomic picture as a backdrop

Fundamentally, the current state of the economy measured against the FOMC's dual mandate is, at the very least, satisfactory. By almost any measure and for nearly every demographic group, unemployment is at decades-low levels. Last week's strong employment report confirmed that the labor market remains healthy.

Of course, even in this relatively rosy context, there are distributional issues that we can and should worry about. I know many in this room share my view on this. But the solutions to those issues require fiscal and other policies that go to the heart of structural impediments to economic mobility and resilience. The best role for monetary policy is to support the general health of the economy, so that the attention of other policy domains can focus on those structural issues.

Exceptionally low unemployment and robust job growth have been achieved without the inflationary outcomes that history might suggest would accompany such strong labor market performance. In fact, to the extent that there is concern about the FOMC's price stability mandate, it is not that inflation is too high, but that inflation is too low.

That may sound odd. If you came here from Mars and found policymakers fretting over good employment growth and low inflation, you would likely wonder about what strange objectives the FOMC might have. The fine print of the FOMC's definition of price stability—two percent inflation over the longer run—probably would not help you understand the consternation.

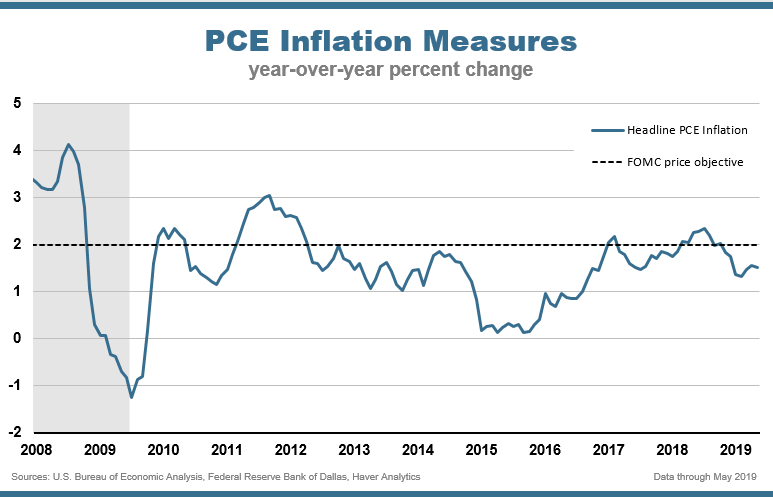

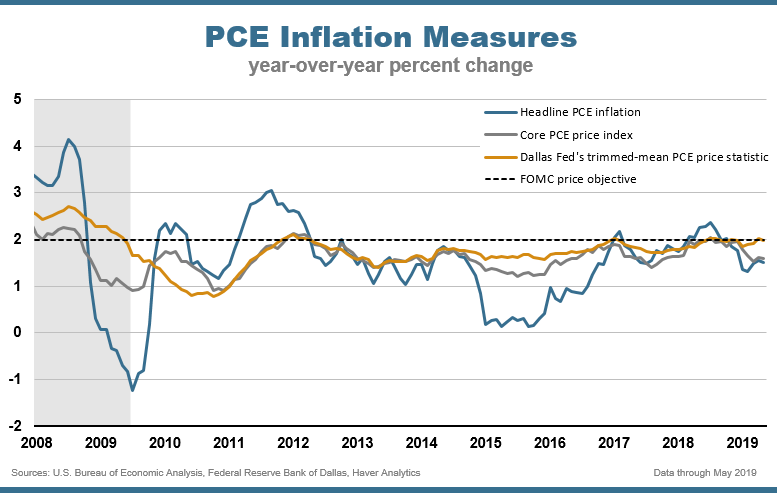

I understand the confusion, but let me try to explain the potential problem that my colleagues and I worry about. As the chart I am showing you illustrates, inflation has systematically fallen short of the FOMC's two percent goal for most of the recovery. Not by a lot, but Fed policymakers have made it very clear that we are concerned about inflation rates that are persistently below or persistently above our objective. If the public comes to believe that a persistent downside miss to the two percent goal means the FOMC is not committed to that goal, then there is a problem.

When assessing this chart, I ask myself two questions. First, is it plausible to argue that current policy is no longer supporting progress to our inflation target as we move forward? Second, has the long period of sub-two percent inflation caused private decision-makers to alter their expectations of what the FOMC can and will deliver?

Let me turn to how I am thinking about the answers to these two questions.

How do we know if we're achieving our goal?

The FOMC's statement of longer-run principles makes it clear that we care about the trend growth rate in the headline Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, but assessing how close that trend is to our two percent goal isn't as straightforward as it might sound. Let me explain.

First, the PCE price index measures changes in the prices of a broad set of retail goods and services purchased by consumers. Prices can change for many reasons, and often a sharp price change in one or a few items can make the overall PCE price index really volatile on a month-to-month or even year-to-year basis. This volatility in the headline price index makes it difficult for policymakers to get a handle on where the inflation trend is or where it is heading.

Getting a more accurate read on that underlying trend inflation rate involves removing sources of noise to extract a cleaner signal out of the price data.

Economists, some of my staff included, have made an entire cottage industry out of developing various underlying inflation measures in search of a cleaner signal.[1]

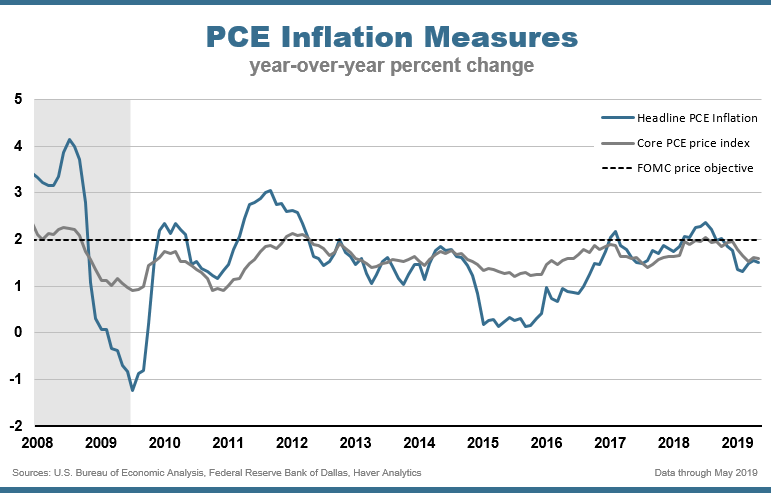

Perhaps the most well-known and often-cited underlying inflation measures are the so-called core inflation measures—those that exclude food and energy prices. The original idea behind core inflation measures was that by removing the two components in the market basket subject to the largest relative price swings, which tended to be food and energy, the resulting price changes would give you a more accurate picture of underlying inflation.

However, there are a couple of key issues with these core measures. First, food prices are not as variable as they once were. Second, and more importantly, by excluding only food and energy prices from the underlying inflation measure, you are treating every other price change in the consumer market basket, regardless of its source, as a signal of underlying inflation.

This means that changes in the prices of stamps, increases in excise taxes on gasoline or tobacco, and changes in the prices of items due to changes in how statistical agencies gather and process certain items all get counted as signals of underlying inflation.

The result is that these core inflation measures that exclude just food and energy prices can still be noisy and give us false signals of changes in trend inflation. This has led to the development of a more general approach to removing noise from retail prices. Trimmed-mean inflation measures—such as the Cleveland Fed's median Consumer Price Index (CPI) and sixteen percent trimmed-mean CPI as well as the Dallas Fed's trimmed-mean PCE. These measures remove noise by excluding the most volatile price changes in the consumer market basket in a given month, regardless of what type of item it is. As a result, they tend to be less volatile than the traditional core measures and have done a better job tracking and forecasting trend inflation.

How close are we to our goal?

Currently, the core PCE price index and the Dallas Fed's trimmed-mean PCE inflation statistic are sending different signals about the trajectory for underlying inflation.

The core PCE measure has softened recently and is running about 0.4 percentage points below the FOMC's two percent target on a year-over-year basis. Most of the recent softness reflects a series of weak readings early in the year, as the annualized growth rate in the core PCE over the past three months is at two percent. In contrast, the Dallas Fed's measure is running at two percent currently and has oscillated very close to two percent over the past two to three years.

Given the advantages that a trimmed-mean approach has in reducing noise and amplifying the inflation signal, I am putting more weight on what that measure is telling me at the moment. And, quite simply, it is suggesting that right now we are very close to our two percent price stability mandate.

How have inflation expectations evolved?

While the inflation that people experience in real time is important, there is a case to be made that what businesses, households, and financial market participants expect to happen with inflation in the future is even more important. This is because planning and investment decisions are forward-looking, making expectations about future economic conditions critical to decision-making.

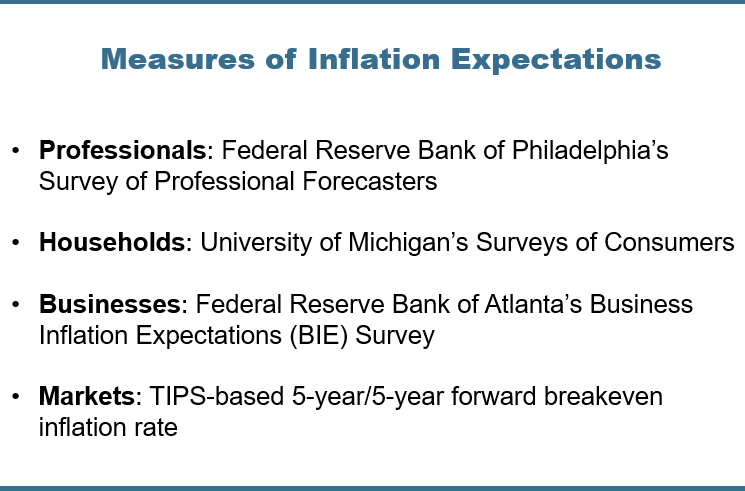

There are multiple measures of inflation expectations, but the ones I tend to lean on the most are survey expectations from professional forecasters and businesses. Specifically, I pay close attention to the Philadelphia Fed's Survey of Professional Forecasters and the Atlanta Fed's Business Inflation Expectations Survey.

My staff compared the inflation-forecasting performance of three different survey measures—expectations of professionals, households, and businesses—and the market-based measures of inflation compensation derived from Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS. They found that professional forecasters tend to be more accurate forecasters of future headline and core inflation than household survey expectations or market-based measures. Further, my team found that, in recent years, business inflation expectations are about as accurate as professional forecasters in forecasting future inflation.

These findings dovetail with earlier work by Andrew Ang, Geert Bekaert, and Min Wei in 2007 and research at the San Francisco Fed in 2015 from Michael Bauer and Erin McCarthy that found survey-based inflation expectations—professional forecasts in particular—to be more accurate than other approaches to forecasting inflation, including market-based measures.

Perhaps it will come as no surprise that professional forecasters are, well, good forecasters. After all, they are typically well-informed regarding the models, data, and indexes associated with inflation dynamics.

But the forecasting performance of business inflation expectations might seem a little surprising, especially since they are surveyed about their expected unit costs and not an inflation statistic. On the other hand, businesses are actually responsible for setting prices. To the extent they act on their expectations, this should lead to an accurate projection of inflation.

Importantly, the longer-run forecasts of professionals and businesses have remained relatively stable and have shown no signs of significant deterioration in recent years.

In contrast, many economists and analysts, including some of my Federal Reserve colleagues, have pointed to a material deterioration in market-based measures of inflation compensation as evidence that the nominal anchor for price stability is slipping too low. This, they argue, has implications for the Federal Reserve's ability to hit its two percent inflation target in the future.

I interpret these data a bit differently, and I'm not convinced that these movements are signs of slipping expectations. I remain skeptical that market-based measures are clearly signaling a significant decline in inflation expectations because (1) these measures are highly correlated with one particular relative price change, the price of oil, which is unrelated to inflation over the long run, and (2) they capture a wide range of factors related to liquidity and term premiums that are unrelated to forward expectations of inflation.[2]

Research by Atlanta Fed economists has found that, after taking these other factors into account, financial market inflation expectations have actually remained relatively unchanged in recent months.

Conclusion

So, how should we think about the Fed's performance in meeting its two percent target? Speaking for myself, I would be very concerned about a continued failure of the FOMC to achieve its inflation target. I would be particularly concerned if such a failure led private decision-makers to adjust their expectations in a way that is inconsistent with the FOMC's stated goals.

But my reading on inflation is that, though it has been below target for some time, the best measures suggest it is close to target and not materially trending away from it. What's more, my preferred data on inflation expectations do not indicate that these expectations are diverging from target either. Combined with ten straight years of growth and a labor market that added more than 200,000 jobs last month, this suggests that the snapshot of the economy is a "keeper."

The policy settings needed to sustain this picture are, of course, what my colleagues and I will be wrestling with at our next FOMC meeting in a few weeks. I do not want to front-run that conversation. As always, I will go into the meeting with an open mind. But I do feel that with respect to both objectives of our dual mandate, we are in a good position.

I'd like to close with a few words about the monetary policy framework. Many of you may know that my colleagues and I are engaging in a systematic review of our framework. One of the principal reasons for doing this is that the world has changed in ways that make it much more likely that we will, at some point, find ourselves in weakened economic conditions that may require a return to near-zero short-term interest rates. This is not the place to go into detail, but the tools to support the economy when interest rates fall to zero invariably work best when the FOMC has credibility about the course it is committed to—that is, when the public believes the central bank will deliver what it says it will deliver.

That is why Chair Powell directed the Federal Reserve to conduct a public review of the strategy, tools, and communication practices we use to achieve our dual mandate, to ensure that we are doing all we can to maintain our policy credibility.

A key element of our review is the Fed Listens series, where we hope to deepen our understanding of how monetary policy affects individuals, communities, and businesses. Next week, in fact, I will be in Augusta, Georgia, for a Fed Listens town hall alongside Governor Michelle Bowman.

While we don't know the ultimate findings of the review, rest assured we are going about it with an open mind. Any changes to the FOMC policy framework will be intended solely to improve our ability to achieve maximum employment and, yes, price stability.

Thanks for taking this journey into the world of inflation and the Fed. If there is time, I'd be happy to take some questions.

________________

[1] Other underlying inflation measures not mentioned in the text but worth noting include the Atlanta Fed's Sticky-Price CPI as well as cyclical inflation measures developed by researchers at the San Francisco Fed and by James Stock and Mark Watson in a recent NBER working paper.

[2] These factors include seasonal carry, limits to arbitrage, margin call liquidations, reallocations, and hedging in the TIPS market following an oil price decline or amid global financial turbulence. For example, an event that drives flight-to-quality into nominal Treasuries or forced sales of TIPS can push market-based inflation compensation lower.