Meeting the Trillion-Dollar Challenge: Fifty-State Review

Disclosure of Deferred Infrastructure Maintenance in Capital Budgeting Documents

INTRODUCTION

The US is estimated to have accumulated about $1 trillion in deferred maintenance, defined as scheduled repairs that should have been carried out but were postponed in favor of more pressing current spending needs. Even though this gap is equivalent to about 4 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product and is expected to continue widening, deferred maintenance is rarely incorporated into state or local capital budgets, annual comprehensive financial reports (ACFRs), or infrastructure needs assessments. The widespread lack of disclosure stands in contrast to financial liabilities such as bond and other debts, pension obligations, and other postemployment benefits—principally health care—which states and municipalities governments are required to report in ACFRs, standardized formats recommended by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board. Still, some states do reveal portions of their deferred maintenance in varying ways.

When deferred maintenance backlogs are reported, the information is often scattered in multiple agencies’ reports or published as a stand-alone document or presentation to the legislature that is intended to inform the capital budget request process. However, if such documents are not directly connected to capital budget documents, the issue of deferred maintenance receives insufficient policy attention and may be neglected.

Capital budgets and centralized capital improvement plans for all fifty states were reviewed to determine which do—and do not—make deferred maintenance disclosures. These capital budgeting documents outline current and future government spending plans for infrastructure and asset investments, and as such should be the tool for states to disclose their strategies and funding allocations to address their deferred maintenance backlogs.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Deferred maintenance in capital budgets

Capital budget documents outline government spending plans for infrastructure and other asset investments. Typically, capital budgets cover infrastructure projects that are costly and have a lifespan of more than one year. In this review, we focused on individual, state-level capital budget documents and executive budget documents that contain a defined section for capital projects; such sections are likely to disclose more detail on projects considered or recommended for funding. We did not focus on operating budgets as they cover day-to-day expenses but may also include capital outlays.

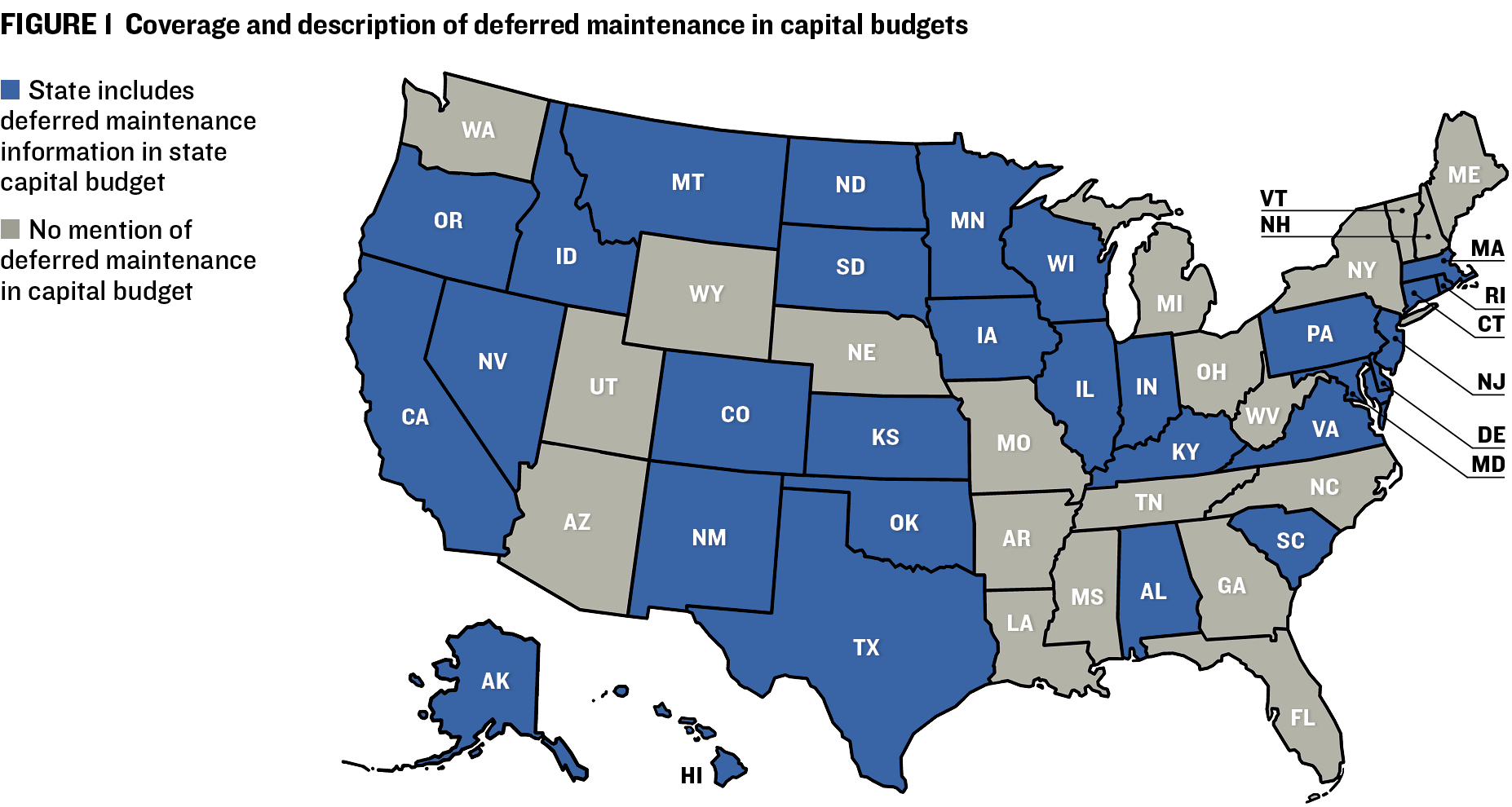

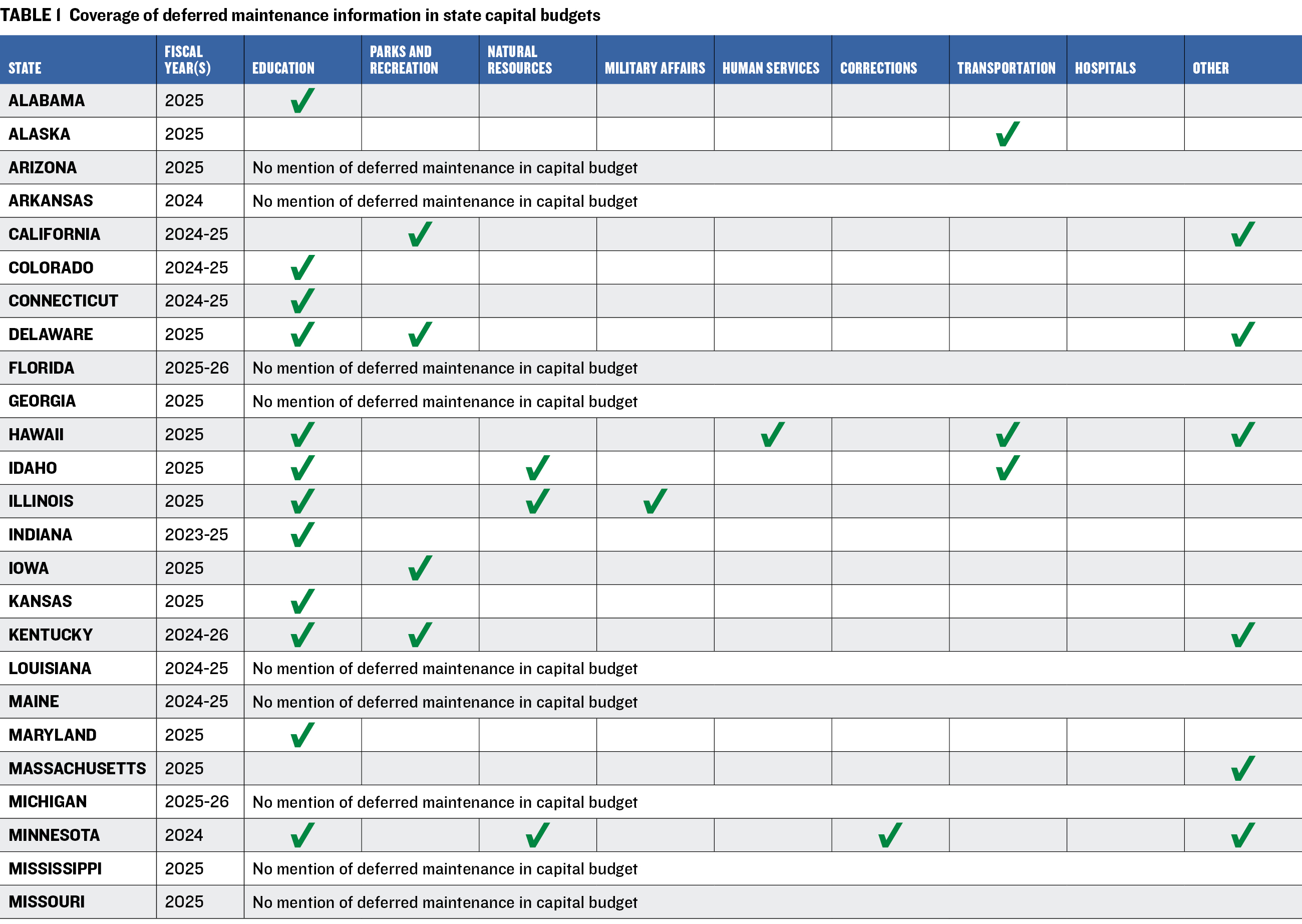

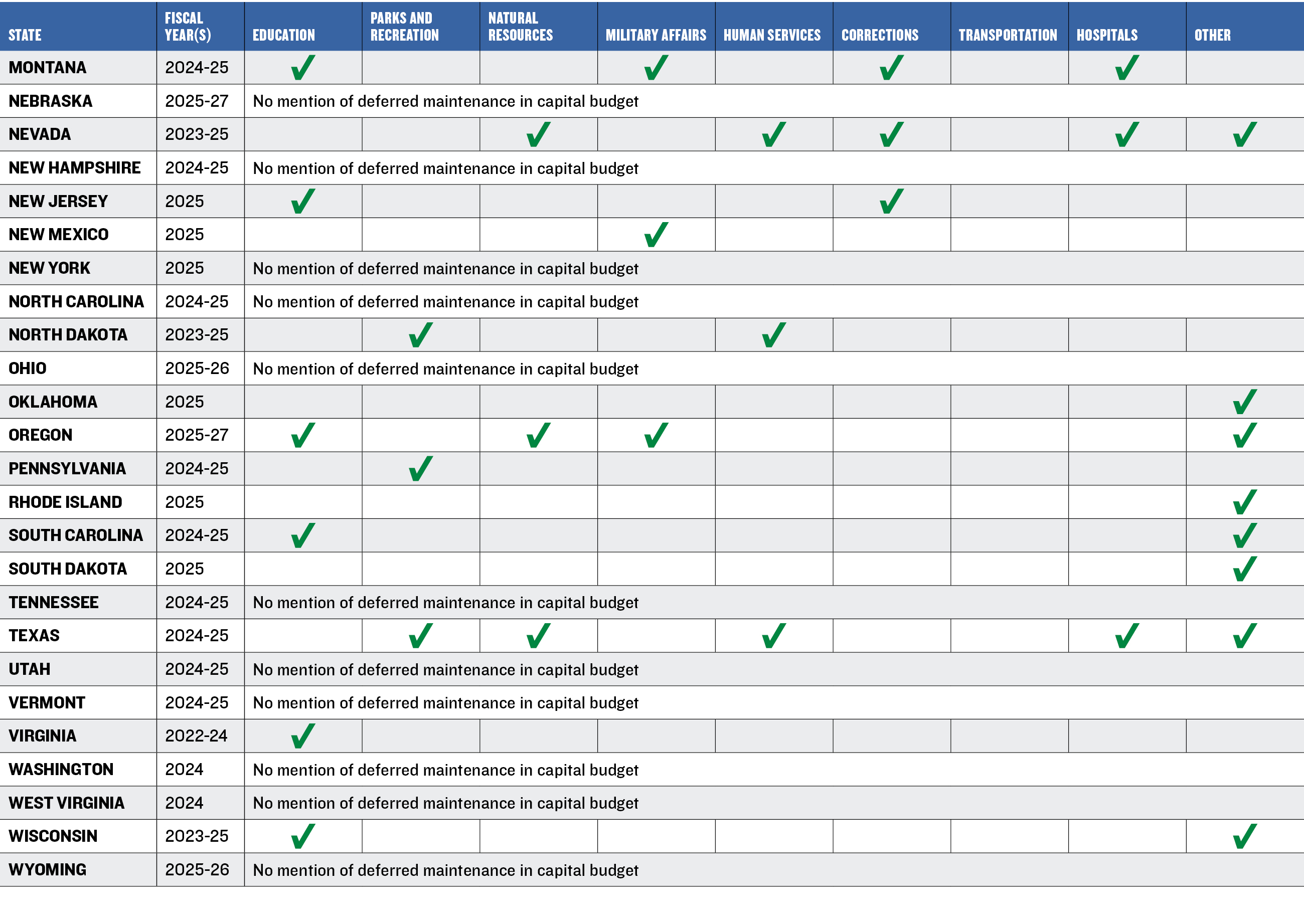

Of the budgets documents reviewed for the fifty states (table 1), twenty lack references to deferred maintenance. Of the remaining states, most refer to deferred maintenance in the context of educational institutions, which includes K–12 and other schools, colleges, institutes, and universities. After education, parks and recreation facilities is the second-most mentioned area, followed by natural resources. Other categories include corrections, military affairs, human services, and hospitals. Thirteen states discuss deferred maintenance in only one area, primarily education. Transportation had few mentions, possibly as state transportation have separate budgets funded by dedicated revenue sources such as motor fuel taxes.

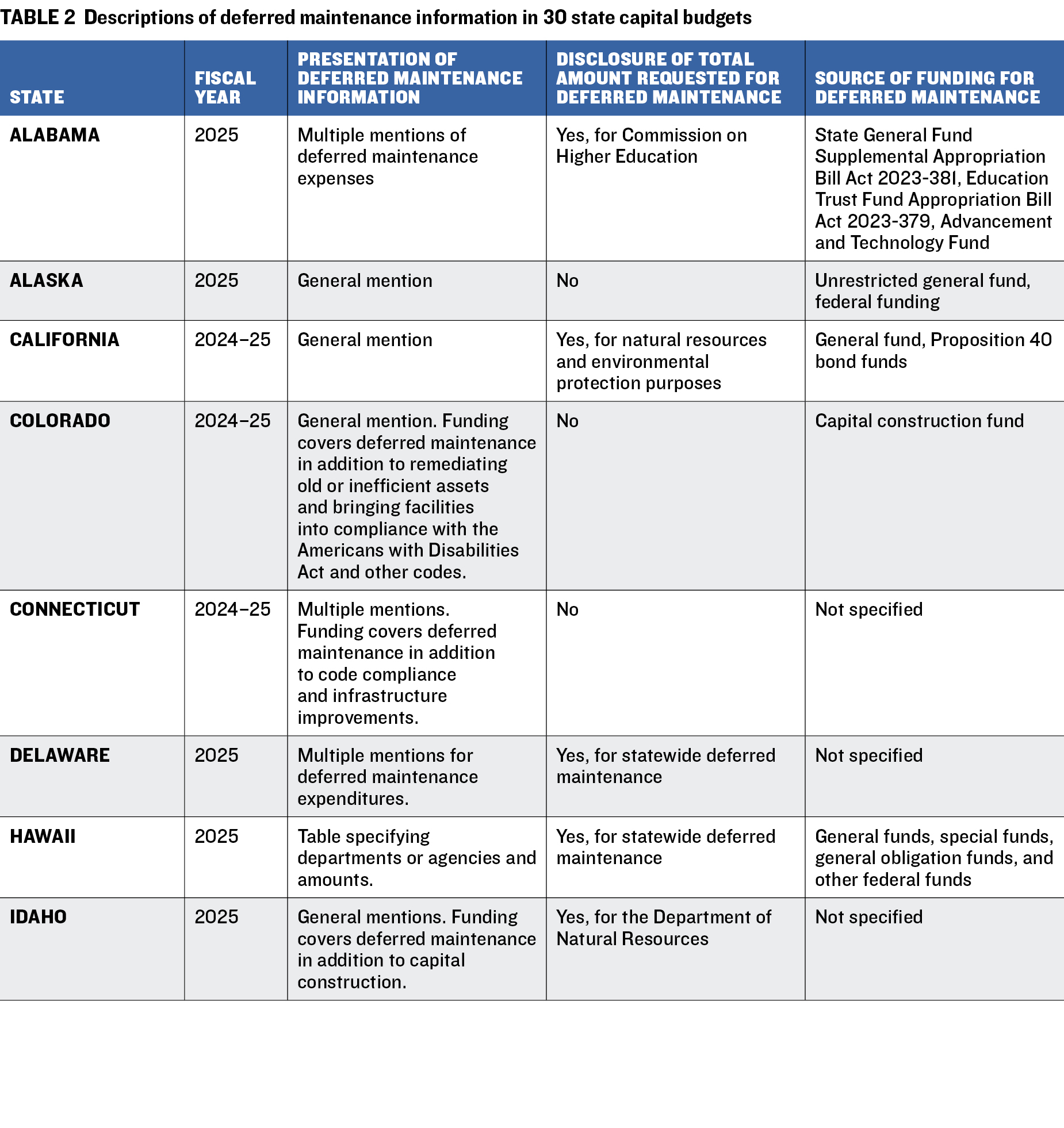

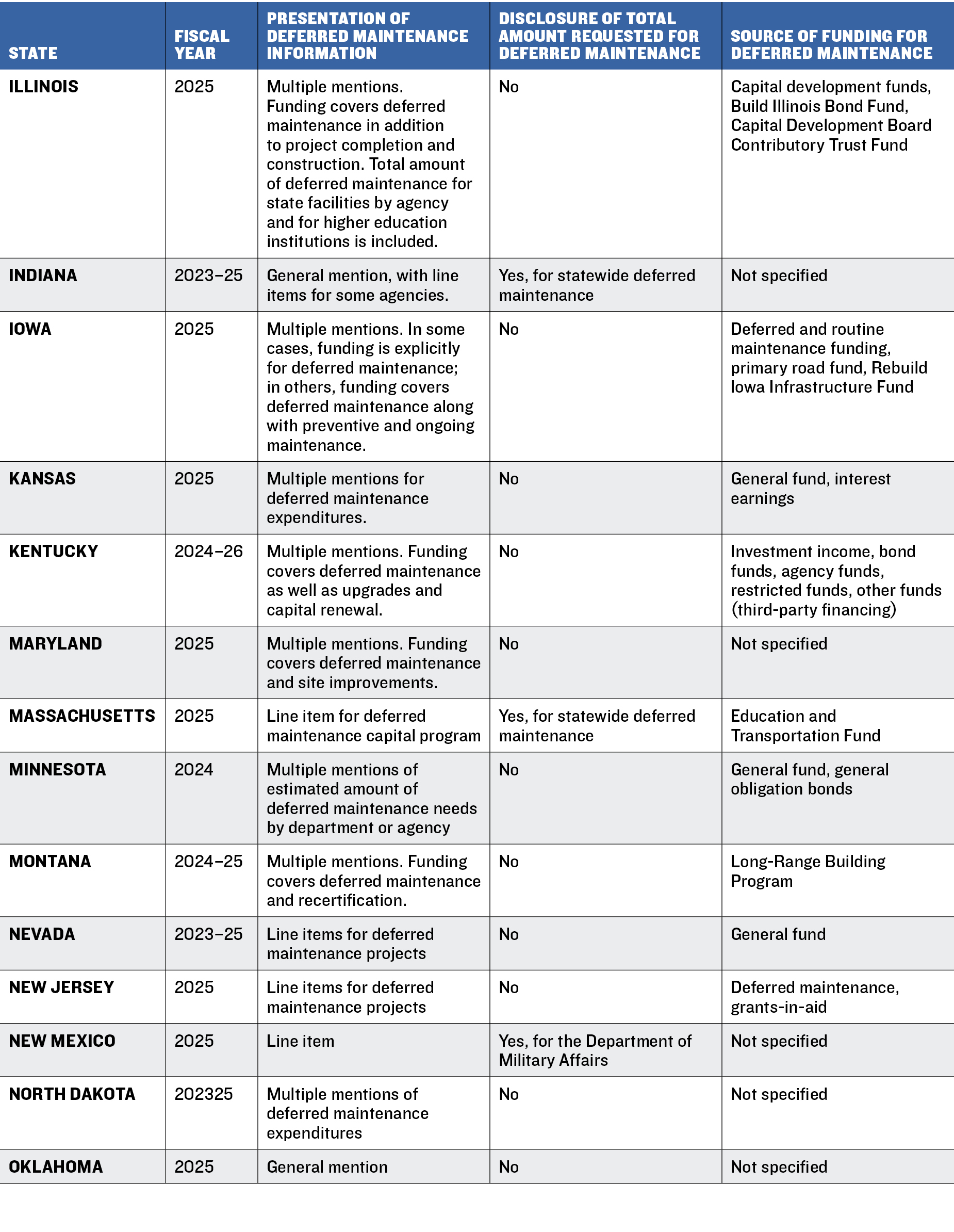

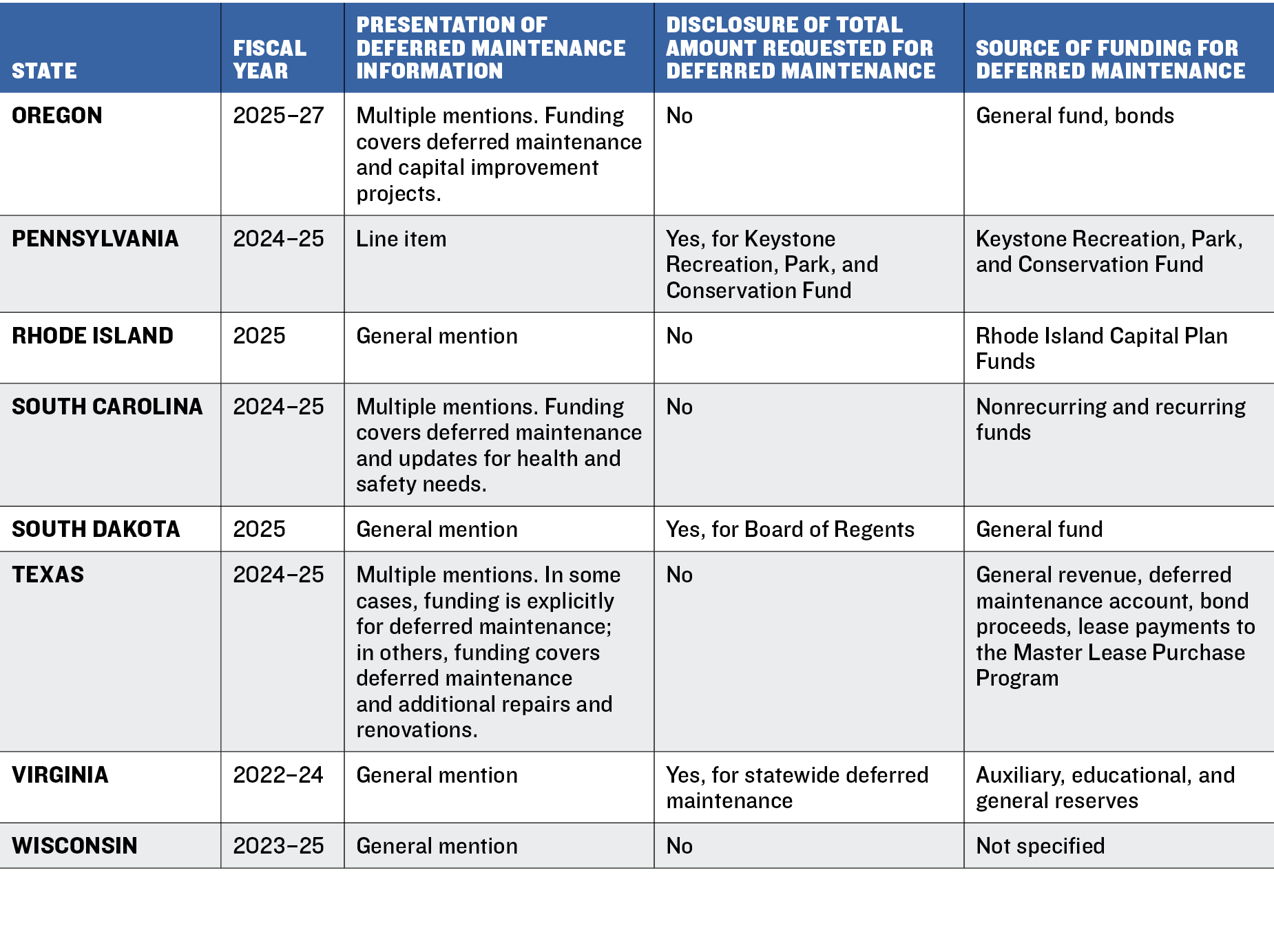

Most of the deferred maintenance mentions in budget documents are in project funding requests. The content of the deferred maintenance mentions varies across states (table 2). Some disclose a dollar amount of funding recommended for deferred maintenance projects, while others provide line items for specific projects. In some states, deferred maintenance is mentioned in language covering other capital expenditures as well.

Some states provide a general mention that discloses a dollar amount needed, recommended, or allocated to address deferred maintenance. For example, one Indiana budget states: “In addition to the above projects, $75 million was appropriated to help with the housing infrastructure, $40 million was given to help with the water infrastructure, and $150 million was given to help with the statewide deferred maintenance.”

Other states disclose dollar amounts for multiple deferred maintenance projects from different state agencies. These mentions are generally scattered through the budget document, a practice that makes it difficult to calculate the total amount of funding requested for deferred maintenance projects. Nevada’s executive budget for 2023–25, for example, included a list of projects and their costs, with some carrying an explanation: “This request funds deferred maintenance projects.” Similarly, the Kansas budget report for fiscal 2025 contained a list of capital improvement expenditures, including deferred maintenance as a line item for state universities. In this case, the total amount of funding recommended for deferred maintenance is noted as part of the summary: “The Governor recommends $40.1 million from the State General Fund for FY 2024 for deferred maintenance and capital renewal of university mission critical buildings and $20.0 million in FY 2025. The funding is to be matched dollar-for-dollar with university resources.”

In some states, deferred maintenance is discussed as part of the use of funding. In the Alabama executive budget for fiscal 2025, the seven uses of funds in the Education Trust Fund (ETF) Advancement and Technology Fund (allocated to K–12 and higher education institutions) include “repairs or deferred maintenance of public education facilities.” However, disclosures may also include other uses. For example:

ALABAMA SCHOOL OF MATH AND SCIENCE "$6,000,000 for one-time capital projects and deferred maintenance expenses to facilities and property used by the school”

ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY “$13,399,461 for deferred maintenance, campus security, renovation of existing facilities, and expenses associated with ongoing capital projects”

ALABAMA COMMISSION ON HIGHER EDUCATION “$7,000,000 for Tuskegee University—administrative expenses for one-time expenses on deferred maintenance, renovation of existing facilities, or expenses associated with ongoing capital projects” and “$5,000,000 for the Deferred Maintenance Program for Historically Black Colleges and Universities”

Deferred maintenance mentions may also include the frequency of funding requested or available to address the needs. Some states explicitly note the unique availability of funding of one-time projects. In others, some recurring funding may be available. In Alabama, the balance of the ETF Advancement and Technology Fund must equal or exceed $10 million in the previous fiscal year to be appropriated and used for deferred maintenance of public education facilities.

Most states covering deferred maintenance in budget documents do not disclose a total amount of funding requested to address the needs in a fiscal period. Of the eleven that do disclose a total amount, five refer to statewide deferred maintenance appropriations. For the remainder, the amount is specific to some departments or agencies.

Two states disclose information about deferred maintenance backlogs but not the funding requested to address them. For instance:

Illinois provides the total amount of deferred maintenance for state facilities by agency and for higher education institutions.

Minnesota’s 2024 Capital Budget Recommendation refers to the state’s estimated deferred maintenance needs by agency but not the total need. A $723.4 million backlog and an estimated $1.55 billion “for state-supported buildings” are among mentions.

Most states that cite deferred maintenance needs in their budget documents disclose the funding source used to address them. These sources include general funds, bond proceeds, and other capital-related specific funding.

Deferred maintenance in centralized capital improvement plans

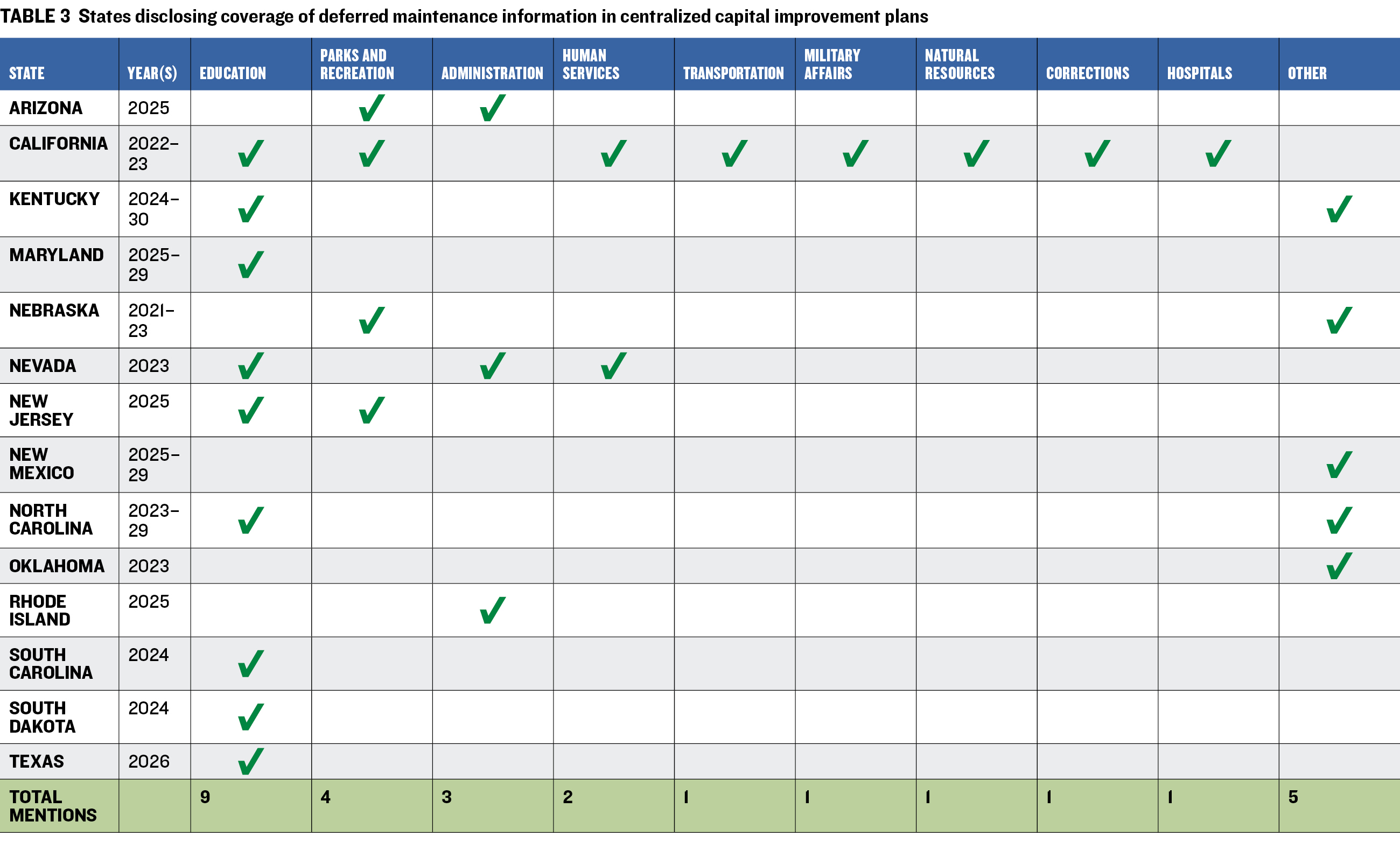

Capital improvement plans (CIPs) typically cover capital projects, often over a time span of five to ten years, allowing for comprehensive planning. Centralized CIPs aggregate capital requests from all state agencies for multiple years in nineteen states that have such a centralized CIP. Other states may have CIPs for each state agency but do not consolidate them.

Of the nineteen states with a CIP, five do not refer to deferred maintenance. The document review showed that, of those that do, two used different terms for it: deferred repairs (New Mexico) and backlog of repairs and renovations (North Carolina).

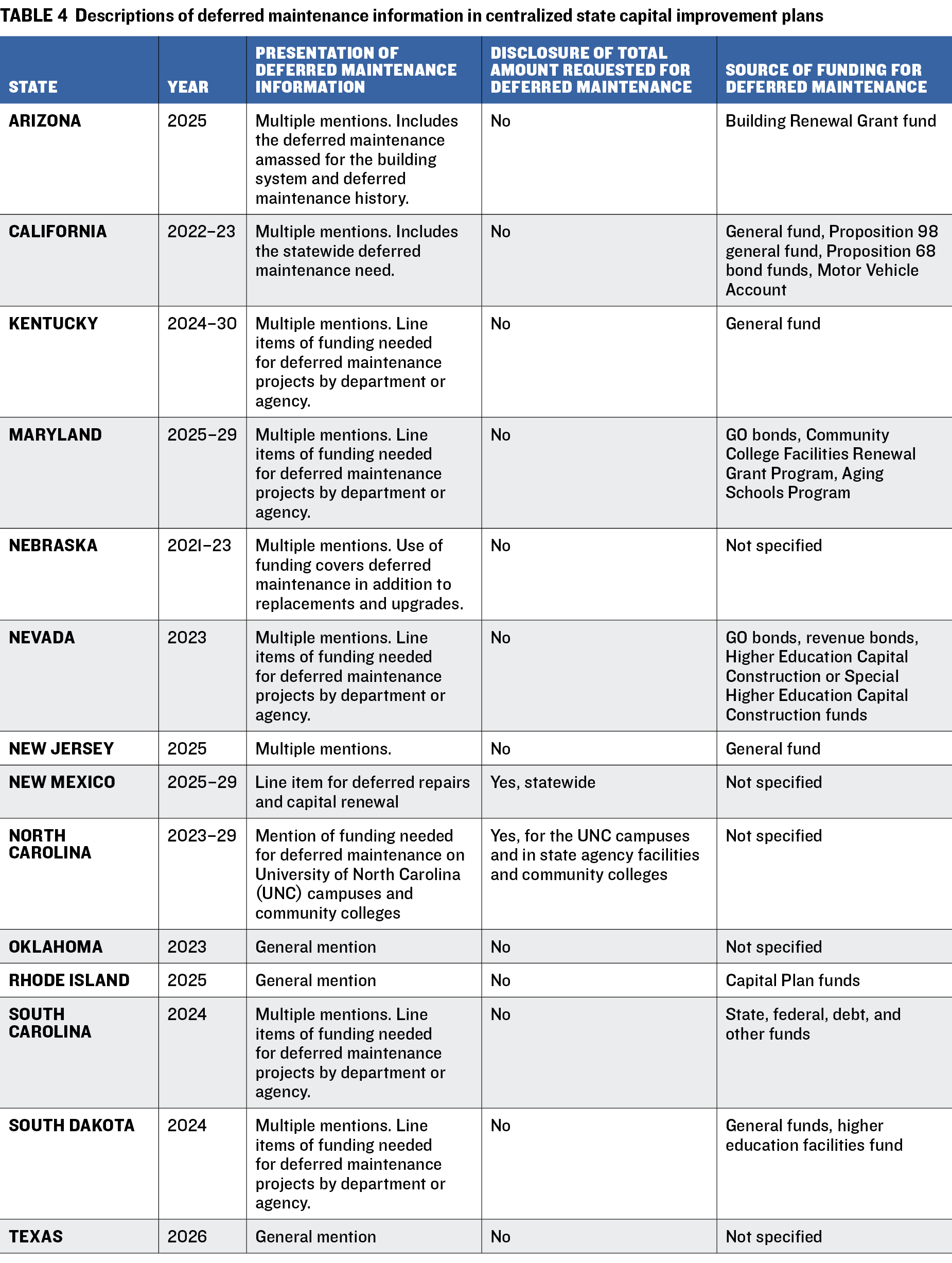

Of the fourteen states that disclose information about deferred maintenance in their centralized CIPs, nine concern educational institutions, including K–12 schools, colleges, institutes, and universities. Parks and recreation is the second most mentioned, followed by administration. Table 3 contains states that include deferred maintenance needs in centralized CIPs and the departments involved, while table 4 describes how deferred maintenance information is presented in centralized state capital improvement plans.

Only Arizona and California provide estimates of the total deferred maintenance accumulated over time. Arizona disclosed annual deferred maintenance needs since fiscal 1989 as well as the total amount accumulated, adjusted for inflation, between fiscal 1989 and fiscal 2024. (The value given for fiscal 2023-24 was negative as it included demolition of obsolete buildings.) California reported statewide deferred maintenance needs of $84.2 billion in its Five-Year Infrastructure Plan of 2022. This amount included $61.5 billion for the Department of Transportation, $7.3 billion for the University of California, and $5 billion each for the judicial branch and Department of Water Resources.

Maryland also presented a list of deferred maintenance needs by institutions in the university system but did not provide a total amount. The deferred maintenance backlog included $1 billion for the University of Maryland (UM), College Park; $186.6 million for Towson University; $271.3 million for UM Baltimore County; $113.2 million for Salisbury University; and $678 million for UM Baltimore.

Arizona is the only state to use a formula to determine the annual appropriation required to fund building renewal. This formula, which was approved by the legislature, is based on construction costs and is calculated as two-thirds of the structure’s value, multiplied by its age, divided by its life expectancy. Of that amount, what is not appropriated constitutes the deferred cost. In fiscal 2024, the total deferred maintenance backlog reached $743 million, adjusted for inflation.

Most states referring to deferred maintenance in CIPs cited funding sources used to address these needs. The sources vary but generally include the general fund and education-specific dollars.

CONCLUSION

Although deferred maintenance may be discussed in annual or biennial state budgets and capital improvement plans, no standardized format for disclosing this information currently exists. Across states disclosing deferred maintenance, data are usually scattered among documents, may be combined with other capital expenditures, and are limited to specific agencies—primarily those related to education. In addition, very few states provide in these documents the total value of accumulated deferred maintenance and the total funding requested to address these needs. The lack of disclosure of this information, especially as liabilities on government balance sheets, hinders effective capital planning and decision-making, as well as the ability to monitor progress in addressing deferred maintenance needs. To close this information gap, states should adopt common procedures and standards for preparing and disclosing deferred maintenance information in budgets and ACFRs. Doing so will provide a framework for consistency and transparency in reporting and addressing a burden.

APPENDIX: List of Budget Documents Reviewed

TABLE 5 Budget documents by state

Notes: *Press release. Florida Capital Budget not available.

TABLE 6 Centralized capital improvement plans by state

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THE RESEARCH TEAM EXTENDS ITS GRATITUDE to the state officials in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Massachusetts, Montana, and Tennessee who generously shared their time and expertise in responding to questions for the case study, both through interviews and written communications. Their thoughtful contributions were invaluable for our understanding of how they assess deferred maintenance needs in their states and thus for shaping the findings of this study. The research team also extends its gratitude to all state officials and transportation officials who generously shared their time and expertise in responding to questions in the fifty-state survey.

The research team wishes to thank Kaitlyn Freeman and Merlene-Patrice Quispe for their valuable assistance in gathering critical information for several of the case studies, and to Wenqi Zhao for his assistance in gathering information for the fifty-state review. Their support was important to the successful completion of the project.

The research team wishes to thank the staff members at the Volcker Alliance who provided us with invaluable support and advice:

- Noah Winn-Ritzenberg, Senior Director, Public Finance

- William Glasgall, Public Finance Adviser

- Graham Dowd, Program Manager

- Nathalia Trujillo, Associate Director, Public Finance

- Divine Adeniyi, Program Assistant, Public Finance

- Melissa Austin, Chief Operating Officer

- Idalis Foster, Communications Manager

This report was supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts. The findings and recommendations are not necessarily endorsed by the supporting organization(s). The research team would like to extend gratitude to David Draine, Fatima Yousofi, Andrea Wales, Emma Wei, Aleena Oberthur, Mary Murphy, Corryn Hall, and Sara Dube of The Pew Charitable Trusts for their contributions to this report

© 2025 VOLCKER ALLIANCE INC.

Published October, 2025

The Volcker Alliance Inc. hereby grants a worldwide, royalty-free, non-sublicensable, non-exclusive license to download and distribute the Volcker Alliance paper titled Meeting the Trillion-Dollar Challenge: Disclosure of Deferred Infrastructure Maintenance in Capital Budgeting Documents (the “Paper”) for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the Paper’s copyright notice and this legend are included on all copies.

This paper was published by the Volcker Alliance as part of its Capital Budgeting and State Deferred Maintenance project. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Volcker Alliance. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Don Besom, art director; Michele Arboit, copy editor.