Balancing Budgets in a Postpandemic World

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

THE AMERICAN RESCUE PLAN ACT OF 2021 (ARPA) authorized unprecedented levels of federal financial assistance to help state and local governments address the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 and maintain essential public services. While this assistance is helping meet critical needs, it also increases the risk of budgetary shortfalls if one-time federal aid is used to finance recurring costs. At the end of 2026, when pandemic relief funds are no longer available, some state and local governments will face fiscal cliffs—the risk of eliminating or scaling back ongoing programs in education, public safety, or other essential areas—if they do not have alternative funding sources in place.

This paper is based on disclosure filings as of July 2022. As of that date, states had allocated 74 percent of the $195.3 billion that Congress provided in the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program under ARPA. Our findings expand upon those contained in the 2022 issue paper The $195 Billion Challenge: Facing State Fiscal Cliffs After COVID-19 Aid Expires.

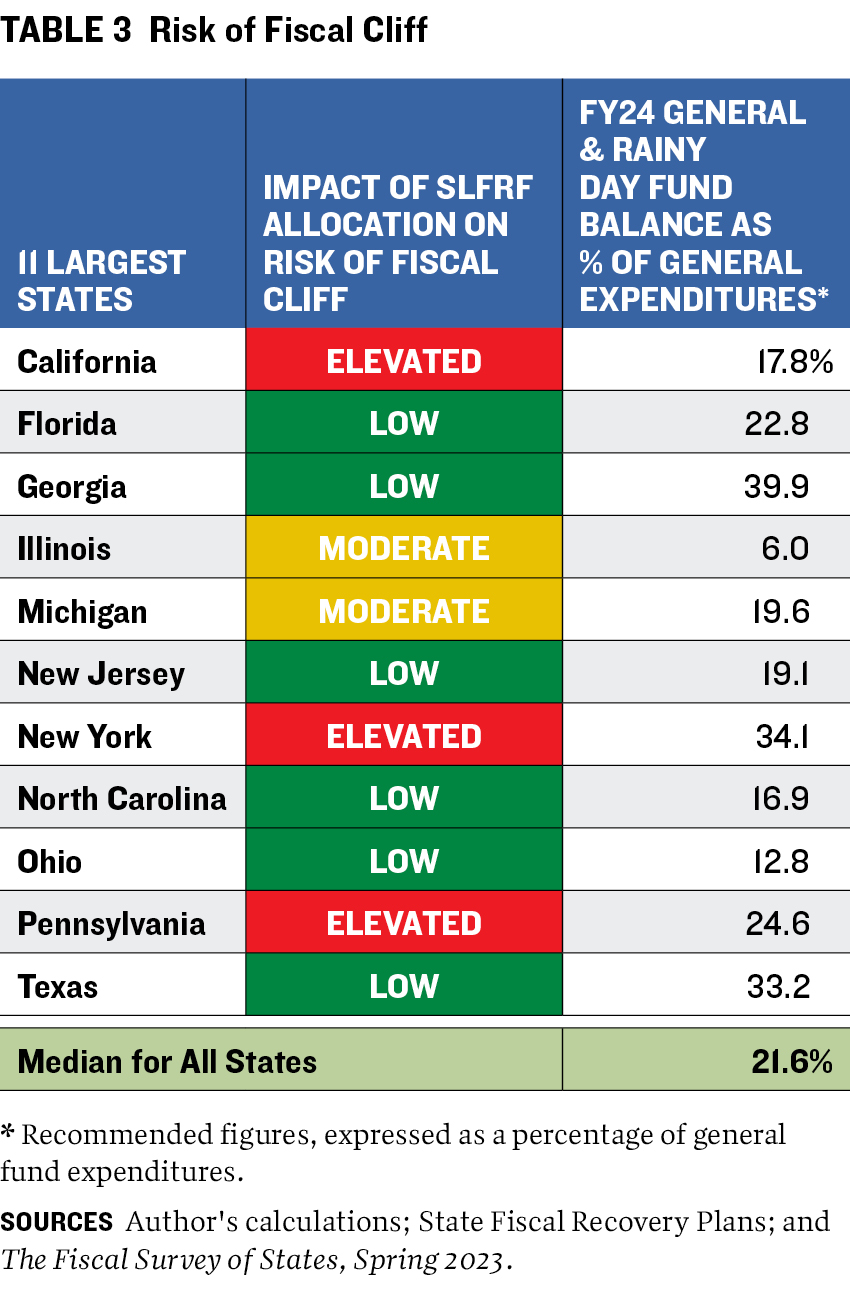

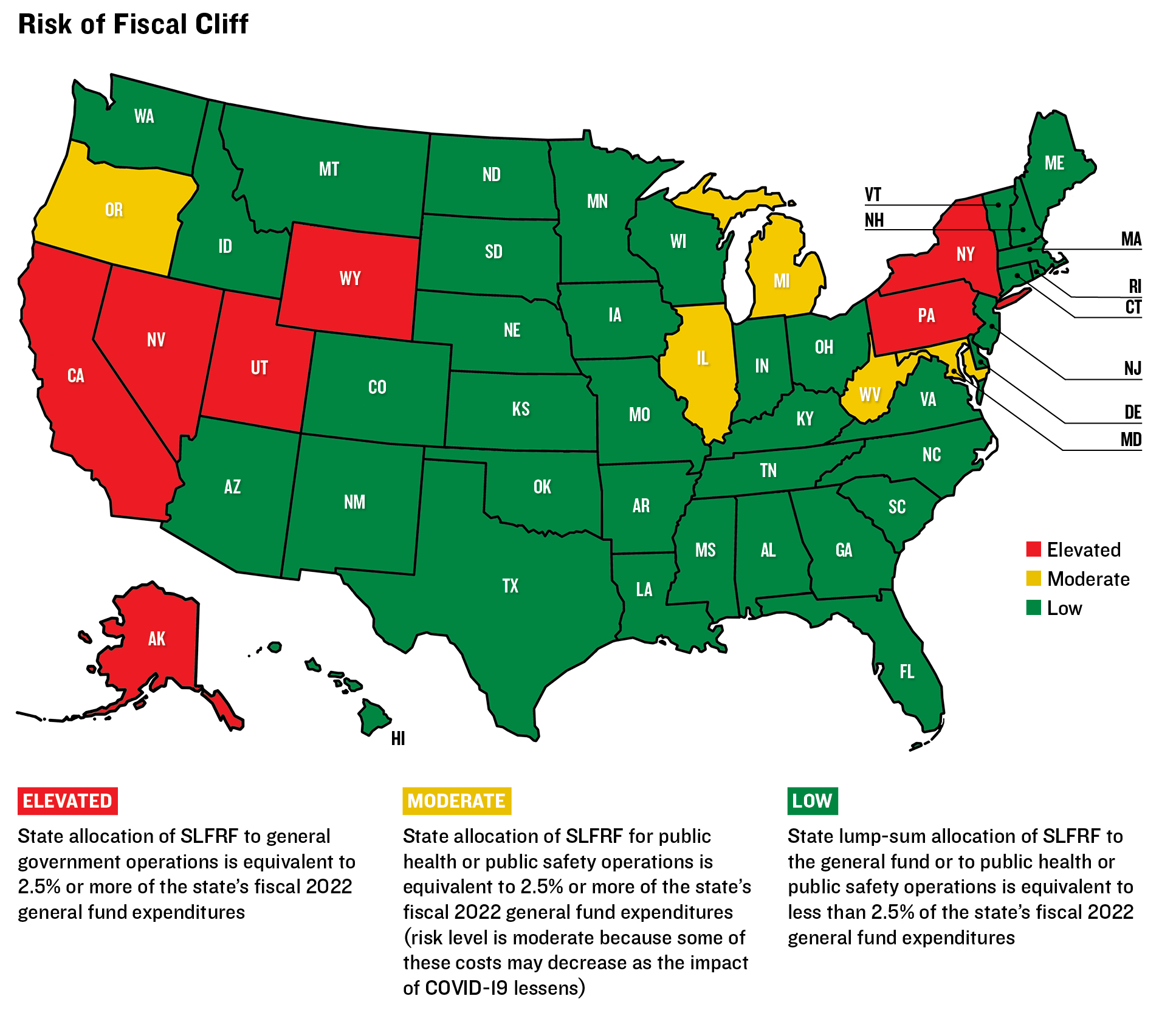

Following our most recent review, we determined that thirty-eight states face a low risk of encountering such cliffs. But among the most populous states, California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania each used SLFRF to cover recurring costs that are equivalent to a significant 2.5 percent or more of their fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures; these states thus face a moderate to elevated risk of encountering a fiscal cliff when federal dollars run out. Together, these big states make up 28 percent of America’s population and almost one-third of total state general fund spending. Several smaller states—including Alaska, Maryland, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming—also tapped SLFRF for at least 2.5 percent of general fund expenditures and thus face fiscal cliff risks as well. The policy recommendations outlined in the box below will help states prevent budgetary shortfalls and strengthen long-term fiscal health after the federal cash runs out.

Key Recommendations

INTRODUCTION

STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS have received unprecedented amounts of federal funding to assist in the response to COVID-19. This includes funds that can be used for public health initiatives and health care, assistance to individuals and organizations that have suffered financial hardship because of the pandemic, and restoration of government services. This paper addresses one of the largest federal programs: the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, under which Congress provided $350 billion to state, tribal, and local governments. These funds must be obligated (a term indicating a binding agreement for outlays) by 2024 and spent by December 31, 2026.1

This paper focuses on the extent to which state governments are using SLFRF for recurring expenditures. This practice could lead to a fiscal cliff, in which a state must cut or eliminate programs unless it has sufficient revenues to continue funding them when federal funds are no longer available. A state with strong revenue growth may be in a better position to avoid a fiscal cliff, depending on how it manages its revenue growth. This paper analyzes states’ allocations of SLFRF but does not assess whether states will have the fiscal capacity to switch to state funding of programs when the federal aid ends.

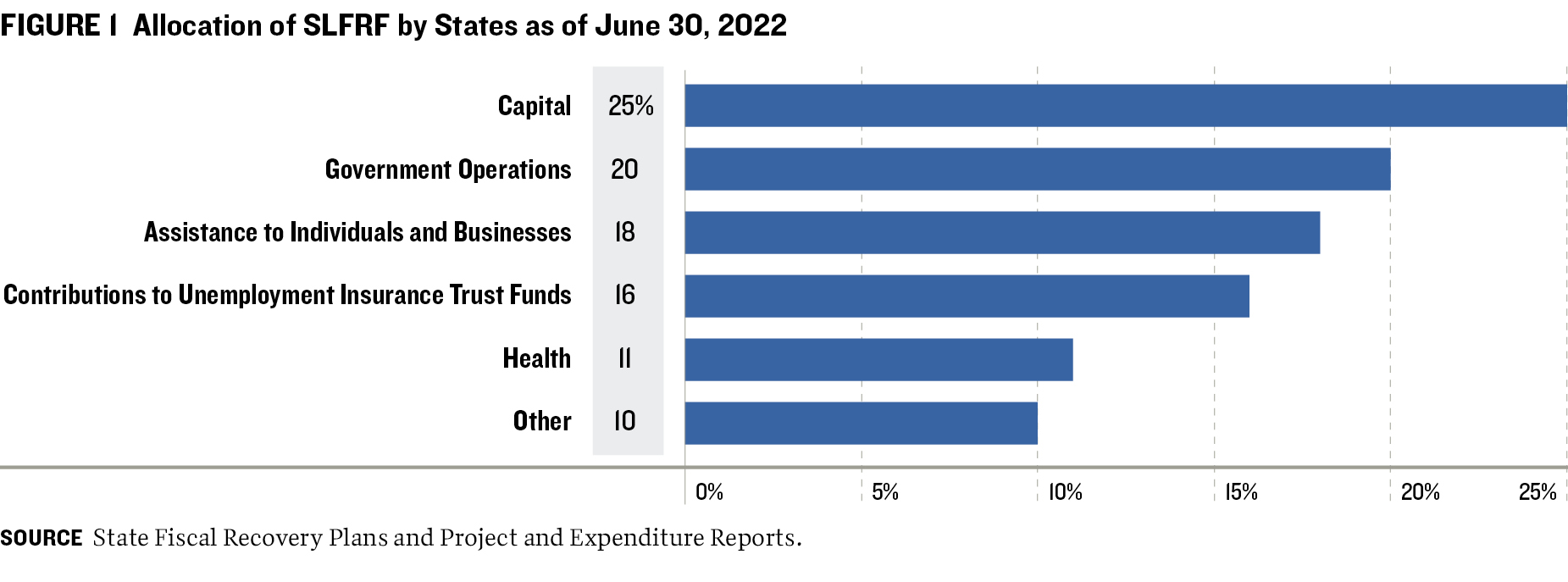

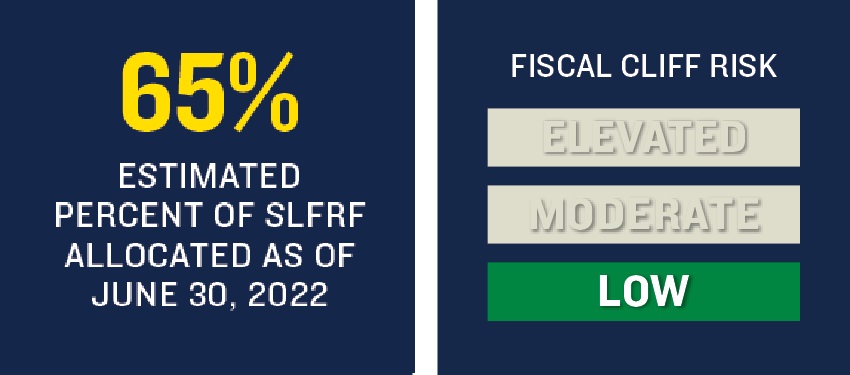

As of June 30, 2022, state governments, in aggregate, had allocated about 74 percent of their SLFRF. The analysis conducted for this paper found that 20 percent of the fiscal recovery funds allocated by that date were being used for government operations (figure 1). This includes such actions as a transfer to the general fund for government operations, restoration of government positions, or allocation of funds to agencies for operations.

Nationwide, our analysis is encouraging: Thirty-eight states (including large states such as Florida, New Jersey, and Texas, as well as smaller states like Iowa and Maine) face a low risk of encountering such cliffs. But among the most populous states, California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania used SLFRF to cover recurring costs that are equivalent to a significant 2.5 percent or more of their fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures and thus face a moderate to elevated likelihood of encountering a fiscal cliff when federal dollars run out. These big states contain 28 percent of America’s population and almost one-third of total state general fund spending. Several smaller states, including Alaska, Maryland, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming, also tapped SLFRF for at least 2.5 percent of general fund expenditures and face fiscal cliff risks. (We detail use of SLFRF funds by the eleven biggest states in the State Report Cards section of this paper.)

Eleven percent of SLFRF grants allocated as of June 30, 2022, were directed toward services such as COVID-19 prevention and treatment, behavioral and mental health services, and violent crime prevention. Some states have used SLFRF for other continuing needs, such as funding for K–12 education, financial assistance to higher education institutions and college students, and assistance to communities.

Some states have also used SLFRF for one-time purposes that carry less risk of a fiscal cliff. For example, states have designated 25 percent of the funds allocated as of June 30, 2022, to support capital projects and 16 percent to repay federal loans to their unemployment trust funds or replenish the funds’ capital. (Some capital projects financed by one-time federal dollars, such as state roads and buildings, and water, wastewater, and broadband facilities, will still need to tap operating funds in the future to pay for operations and maintenance.)

THE CORONAVIRUS STATE AND LOCAL FISCAL RECOVERY FUND PROGRAM

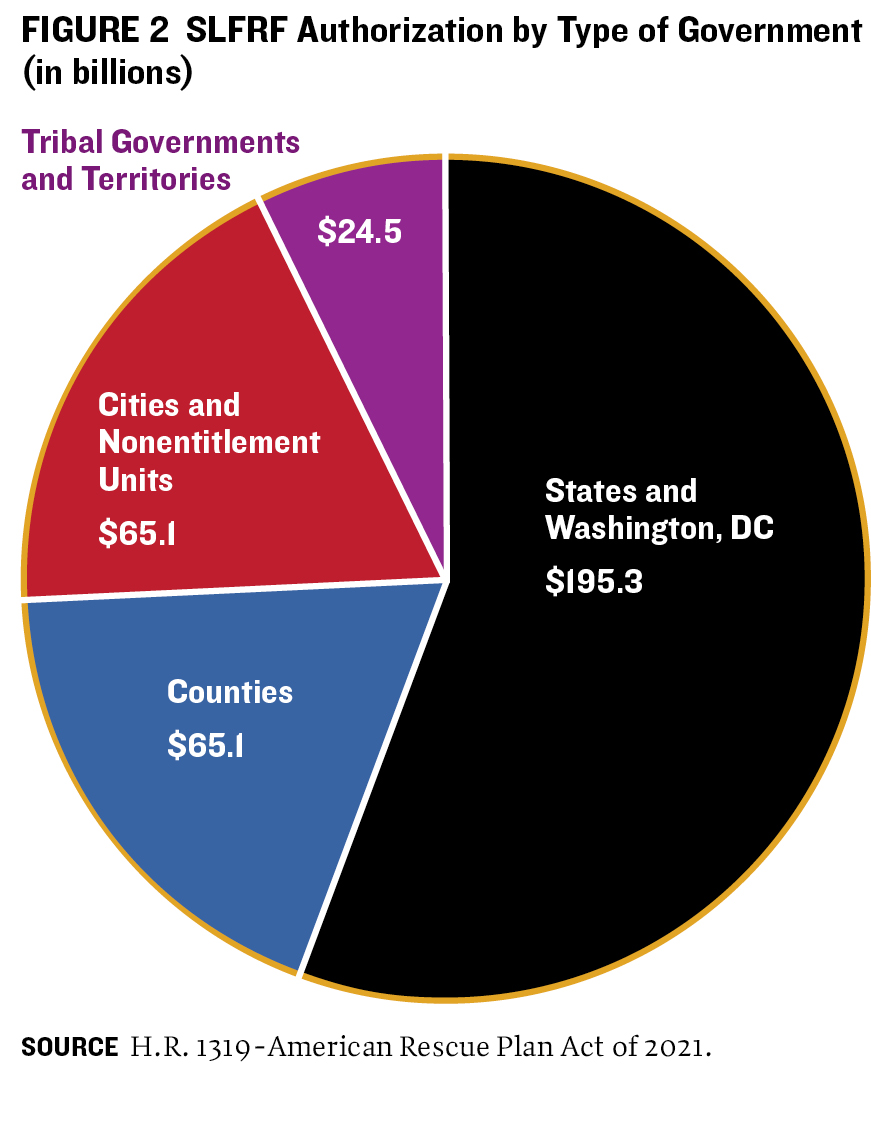

IN MARCH 2021, CONGRESS PASSED the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which authorized $1.9 trillion to respond to COVID-19 after the partial shutdown of the nation’s economy. This included $350 billion for SLFRF: $195.3 billion for state governments and the District of Columbia, and $154.7 billion for local and tribal governments (figure 2).

Each state received $500 million, plus an amount based on the number of unemployed residents as a percentage of the total number of unemployed in the nation.2 If a state’s unemployment rate exceeded its prepandemic rate by 2 or more percentage points, it received SLFRF in one payment in 2021. Other states received half their payment in 2021 and half in 2022. Thirty states received a single payment; twenty states and the District of Columbia received a split payment.3

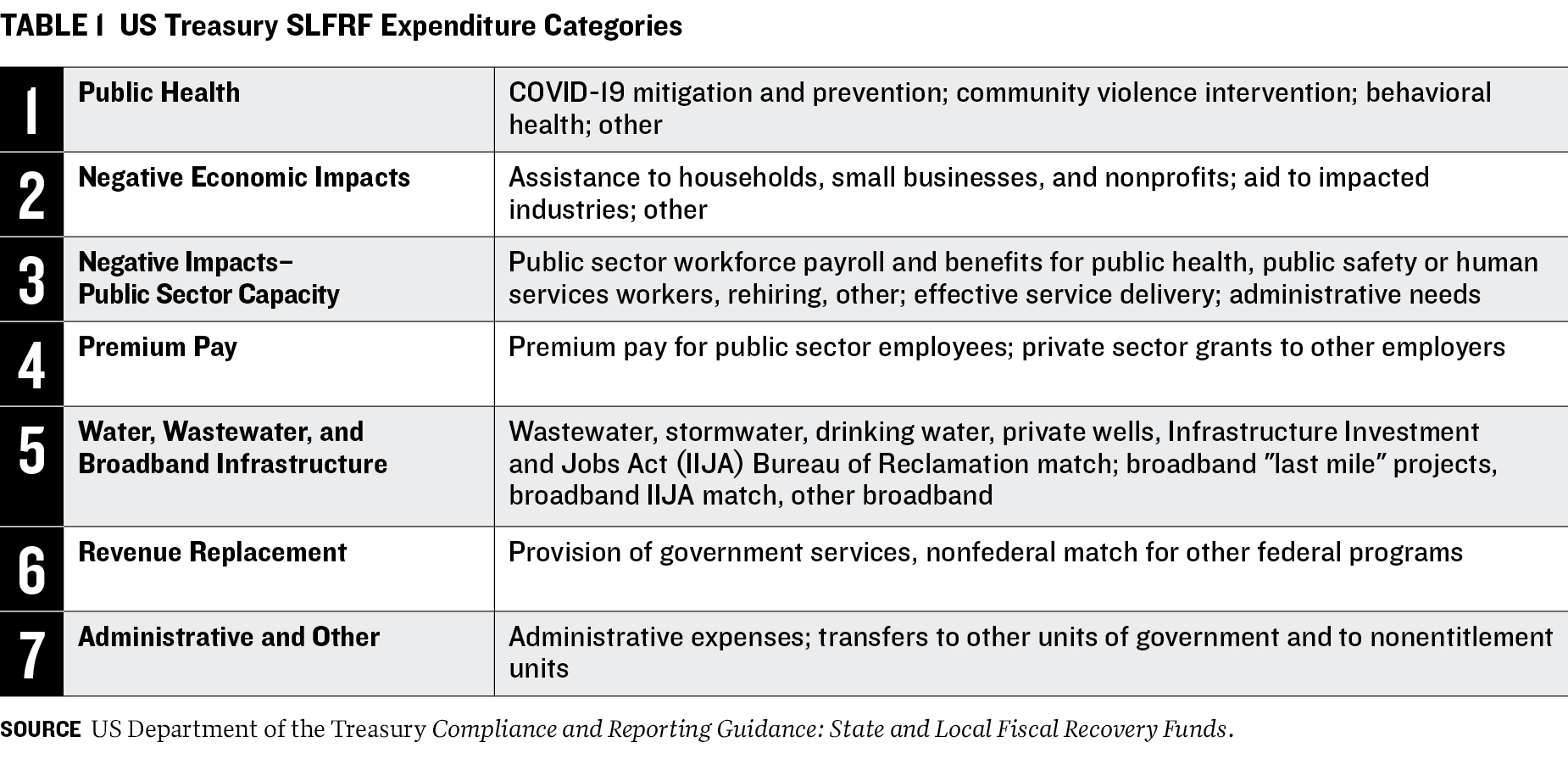

The US Treasury, which is responsible for oversight of SLFRF, issued a final rule that identified seven broad expenditure categories for the use of the federal funds4 (table 1). The infrastructure category is restricted to water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure, but other types of capital projects can be financed under different categories if certain conditions are satisfied. For example, a state can use revenue replacement funds to finance infrastructure maintenance or pay-as-you-go capital projects, such as roads.5 States can also use federal funds under other expenditure categories to finance capital projects such as affordable housing, childcare facilities, schools, or hospitals if the investment supports an eligible COVID-19 public health or economic response.6

While states have discretion to allocate SLFRF among these expenditure categories, there are restrictions on the amounts they can allocate to revenue replacement. The Treasury’s final rule offers states the choice of either a provided formula for estimating revenue loss due to the pandemic or a standard revenue replacement allowance of $10 million. States that use the formula must choose whether to use the calendar or fiscal year to calculate any reduction in revenue at the end of each of the years 2020 through 2023.

The final rule specifies uses of SFLRF prohibited by Congress. States are not allowed to use the funds to pay debt service, finance unfunded accrued pension liabilities, offset revenue losses from state tax cuts, or replenish rainy day or other reserve funds. (Some states have filed lawsuits contesting Congress’s constitutional authority to prohibit the use of the funds to directly or indirectly offset revenue losses from tax cuts.7)

The negative economic impacts category contains one notable exception to the prohibition on using SLFRF to repay debt. Under the category, states may use their federal aid to replenish their unemployment trust funds to the level that existed before the pandemic or to repay federal loans to the trust fund (known as advances) taken out during certain months of the pandemic.8 At the end of fiscal 2019, on the eve of the pandemic and after a record-long US economic recovery, no states had outstanding advances. By the end of 2020, as millions of workers were ordered to stay home and the economy plunged into recession, eighteen states (plus territories and the District of Columbia) had run up $34.1 billion in debt; the amount had swelled to $45.6 billion by the end of 2021.9

Some states have set their own guidelines for using federal aid dollars. Utah, for example, established ten guiding principles for the use of ARPA funds, including that the state consider the full cost of ownership and not create an unfunded future cost10 and that budget documents or appropriations show one-time revenues, which appropriations are financed with one-time funding, and a list of projects funded by SLFRF.11 Kansas, meanwhile, established six primary principles to guide the use of SLFRF, including to “prioritize sustainable programs and investments through one-time use of funds vs substantial expansion of existing services”12

A state’s decision about how to allocate SLFRF may be influenced by the availability of other federal funds—particularly COVID-19-related aid dollars. These funds may comprise money allocated under the Coronavirus Relief Fund (a part of the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act), which had to be spent by December 31, 2021, and various ARPA programs, including the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund ($122.7 billion); Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund ($39.6 billion); Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund ($10 billion); Emergency Rental Assistance Program ($21.5 billion); and Homeowner Assistance Fund ($10 billion).13 The availability of funds through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which was passed in November 2021, may also influence decisions on allocating SLFRF.

HOW THE BIGGEST STATES USED SLFRF

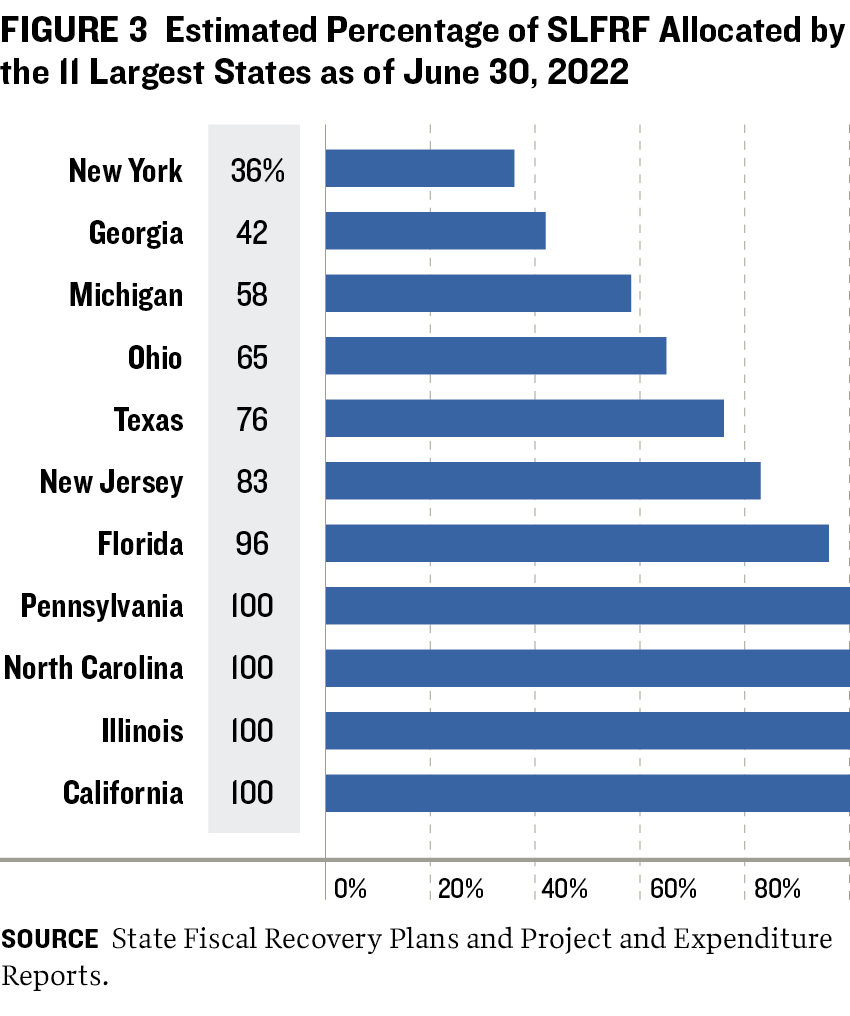

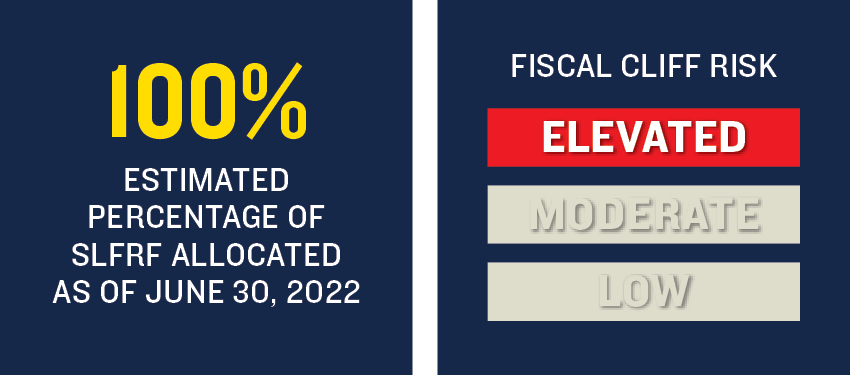

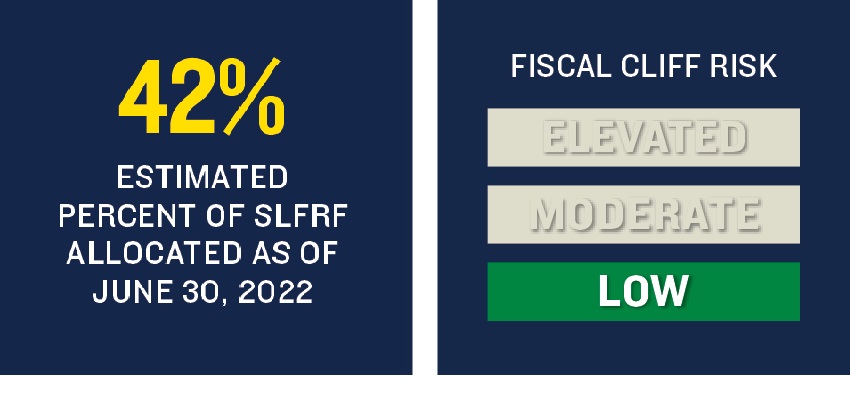

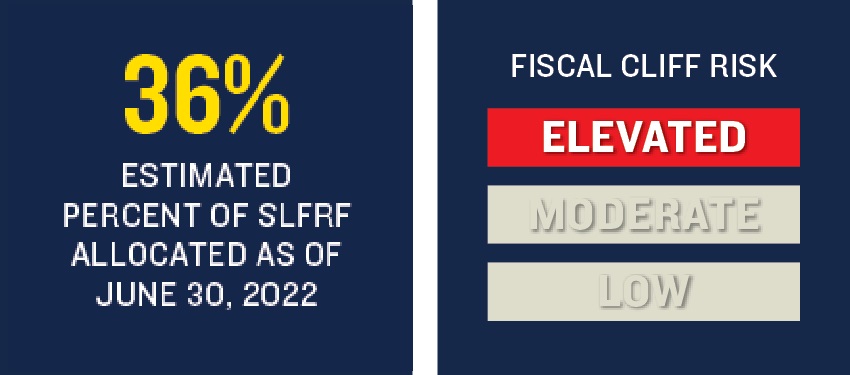

THIS SECTION EXAMINES THE ELEVEN most populous states, focusing on uses of SLFRF that may contribute to the risk of a fiscal cliff when the program expires. New Jersey is included because it was among the top ten states in funds received. The eleven states account for 57 percent of the US population and 55 percent of SLFRF allocated to state governments and the District of Columbia. As of June 2022, the eleven states had allocated 75 percent of their SLFRF, with percentages ranging from 36 percent in New York to 100 percent for California, Illinois, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania (figure 3).

As discussed above, three of the largest states (California, New York, and Pennsylvania) used SLFRF for general government operations and three others (Illinois, Michigan, and New York) designated funds for public health or public safety operations. In each case, the amount of SLFRF for operations was equivalent to 2.5 percent or more of the state’s fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures. Texas also shifted $359 million (or 0.6 percent of general fund expenditures) for compensation for public safety state employees.14

In at least two states—Illinois and New York—the use of SLFRF for operations appears to have freed up own-source recurring revenues that were then applied, at least in part, to one-time purposes: debt repayment (Illinois) and rainy day fund contributions (Illinois and New York). Those states may be able to use those state revenues in the future to cover costs that were temporarily financed with SLFRF.

The largest states are using SLFRF to address needs that may exist beyond 2024, when all the money has to be obligated, and 2026, when it all has to be spent. These include a reading program in Florida ($125 million), temporary expansion of eligibility for special education in New Jersey ($604 million), a preschool program in Michigan ($121 million), assistance for higher education in Pennsylvania ($175 million) and Texas ($50 million), and Appalachian  community grants in Ohio ($500 million). In addition, states are using SLFRF to pay for local law enforcement assistance (Pennsylvania, $135 million), anti-violence programs (Ohio, $250 million; Illinois, $70 million; Pennsylvania, $75 million; and Texas, $52 million) and crime victim services (Texas, $55 million; and Georgia, $50 million). States may need to cut back on these services if they are unable to identify alternative funding sources once the federal assistance is spent or expires.

community grants in Ohio ($500 million). In addition, states are using SLFRF to pay for local law enforcement assistance (Pennsylvania, $135 million), anti-violence programs (Ohio, $250 million; Illinois, $70 million; Pennsylvania, $75 million; and Texas, $52 million) and crime victim services (Texas, $55 million; and Georgia, $50 million). States may need to cut back on these services if they are unable to identify alternative funding sources once the federal assistance is spent or expires.

Some states, such as Michigan, disclosed starting and ending dates for specific programs in their fiscal 2022 recovery plans, which signals that services will not continue beyond the specified date. Across the nation, however, state officials who use SLFRF to provide financial assistance to businesses, individuals, health care organizations, or local communities may face political pressure to continue spending state revenues on what may be considered critical needs—say, nursing homes or hospitals in rural communities. Such choices may involve spending and job cuts for other state-funded programs with less political support.

Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Texas dedicated SLFRF to repay federal unemployment trust fund loans or replenish state unemployment trust fund capital—both one-time purposes. These uses account for just 4 percent of SLFRF allocated as of June 30, 2022 in Michigan. It accounts for 33 percent in Illinois, 58 percent in Texas, and 68 percent in Ohio.

Unlike paying for recurring expenditures with one-time federal funds, investing in water, wastewater, or broadband infrastructure projects is less likely to contribute to a fiscal cliff. As of June 30, 2022, three states (Georgia, Michigan, and North Carolina) had invested at least one-third of their SLFRF in these types of infrastructure projects. Three others (California, Florida, and Ohio) have put 10 percent or more of their funds toward such investments.15

These figures understate the amount of SLFRF allocated to infrastructure because some states, such as Florida, are also using part of their revenue replacement funds for infrastructure and facilities. To the extent the infrastructure or facilities will be maintained and operated by a state agency, the state will need to identify funding sources for those costs.

The discussion in this report, including the report cards on the eleven biggest states, is based primarily on state fiscal recovery reports and project and expenditure reports covering the period ending June 30, 2022. (A guide to tracking SLFRF spending, including a hyperlink to a library of state reports, can be found in appendix B, beginning on page 45.) The timing of these reports presents challenges in that some states included SLFRF projects and programs authorized in the fiscal 2023 budget, while others did not.16 For the latter, we scrutinized enacted 2023 budgets for disclosures on the use of SLFRF by the eleven largest states. Such information is not available for every state.

INSIGHTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

THE INFLUX OF SLFRF INTO STATE BUDGET COFFERS created opportunities and challenges for governments. One of the challenges is how to manage the use of these funds to avoid shortfalls or service cuts when the federal funds run out. If SLFRF are used to finance recurring needs, a state will need to either eliminate or cut back operations or programs when the funding ends or identify other revenues to continue them.

Our analysis found that some states are using SLFRF for recurring purposes. Of the funds allocated as of June 30, 2022, 20 percent went to government operations, some of which are likely to be ongoing. Twelve states, including Michigan, which reported in August 2022, allocated SLFRF to government operations in amounts equivalent to at least 2.5 percent of their estimated fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures. SLFRF are also being used to finance other programs meeting needs that are likely to continue after the federal aid ceases. This includes mental health and substance abuse programs, violence prevention, and and pandemic-related initiatives. Other programs, such as those assisting communities or providing educational assistance or workforce training, also address recurring needs.

To help craft strategies for dealing with this dilemma, states should prepare inventories of programs that may be affected by the cessation of federal pandemic aid. One approach, which the New York State comptroller developed for New York City, is to compile a list of programs that have received temporary federal funding and show the budget shortfall amounts for future years.17 This allows government officials to see how much in aggregate is needed to avoid shortfalls. They can then assess revenue options or whether program reductions will be necessary.

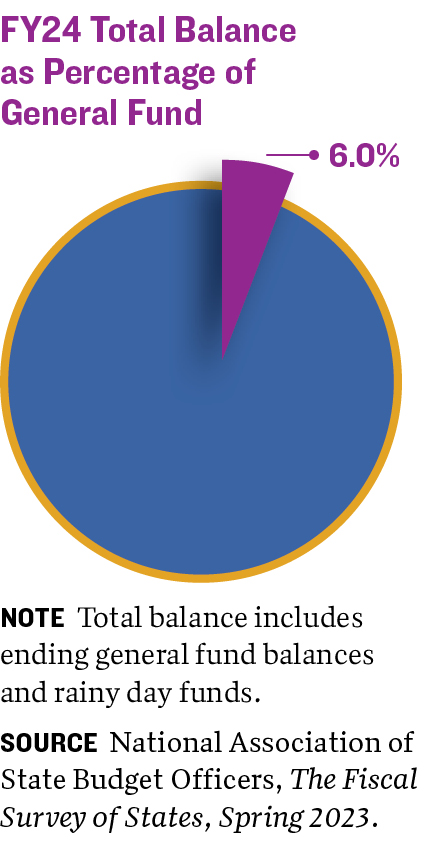

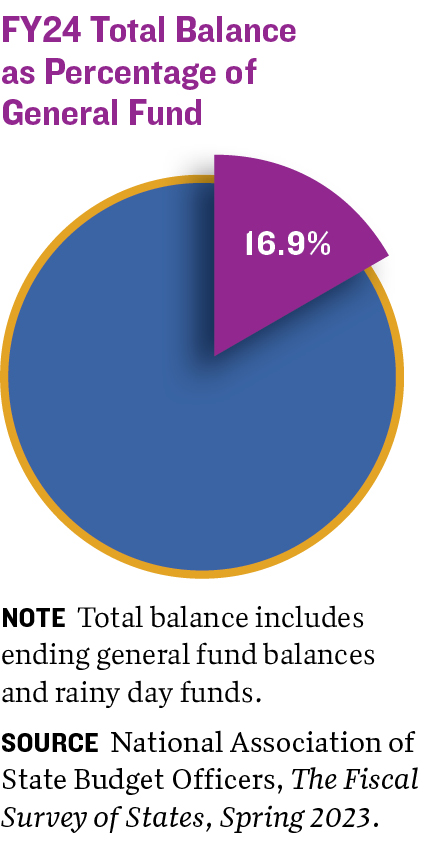

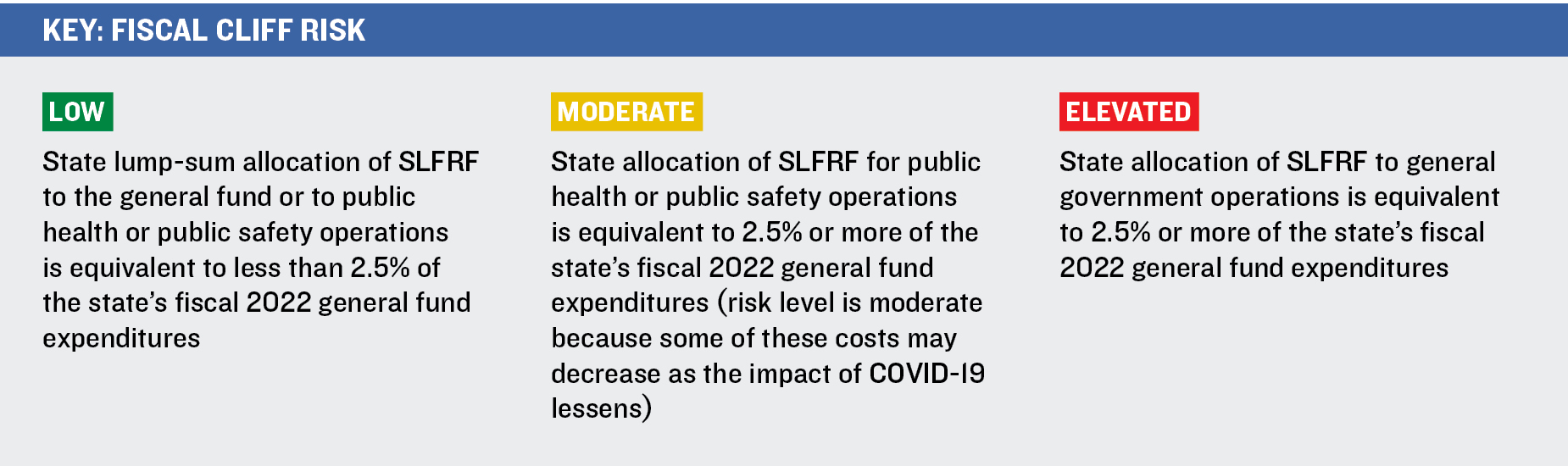

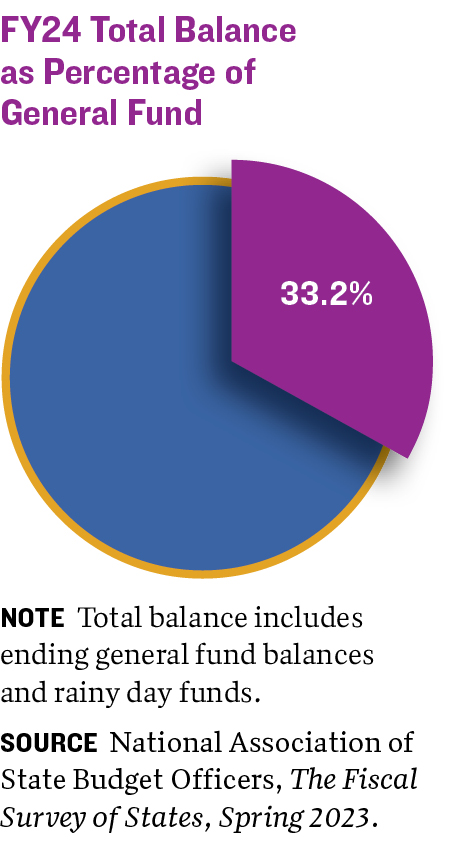

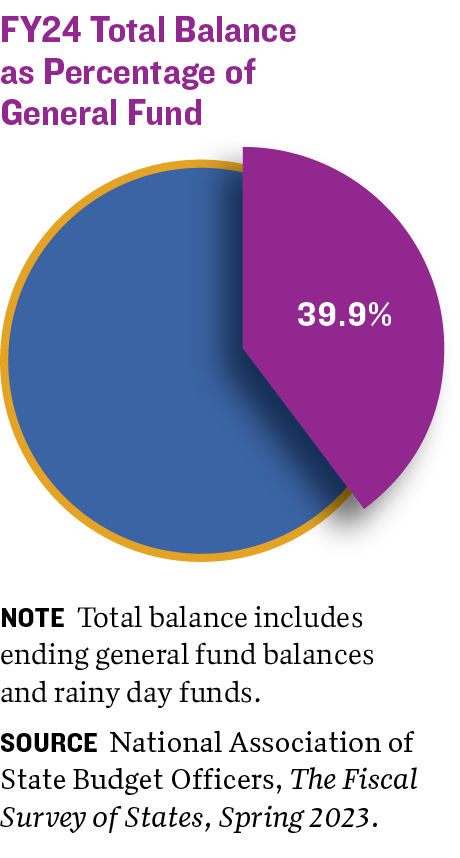

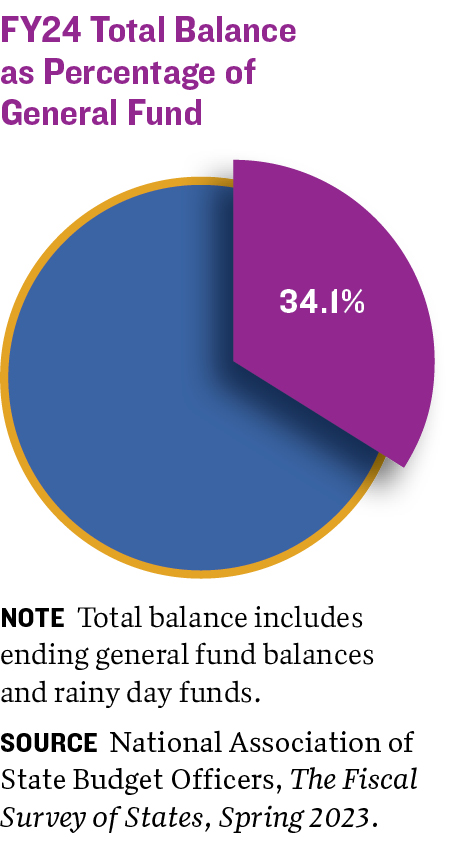

States that used SLFRF for government operations will need to conduct multiyear revenue and expenditure forecasts to determine whether there will be sufficient revenues to cover that spending. States with strong revenue growth may have enough money to cover the programs previously funded with SLFRF, depending on whether the growth is sustainable. States that used revenue growth to fund new or expanded programs to address recurring needs—or those cutting taxes in response to the robust economy that followed record injections of federal cash—may face more fiscal challenges than states that used at least a portion of the revenue growth for one-time purposes such as repaying debt or increasing reserves.

Recommendations

State governments should clearly label SLFRF as one-time funds. This can be accomplished in various ways. Florida, for example, has a separate column for nonrecurring revenues and appropriations in its budget financial outlook statement, indicating that these revenues are not a part of the base budget. Utah provides a list of ongoing versus one-time revenues in its budget forecast documents and identifies appropriations that are financed from one-time sources in appropriation bills. Other states, such as Texas, passed separate appropriations bills to allocate SLFRF, which helped highlight programs and operations supported by one-time federal funds.

To facilitate fiscal sustainability, one-time funds such as SLFRF should be used for one-time or short-term purposes. Some states have identified policies or goals that explicitly address the need to consider future fiscal sustainability when allocating SLFRF. For instance, Michigan included a fiscal sustainability criterion in its list of standards for evaluating potential programs to be paid for with SLFRF. Even before ARPA, some states had policies in place regarding the use of one-time revenues.

If a state allocates funds to address recurring needs, it should track that spending and plan for what will happen when the SLFRF program expires. States need to know whether there will be budget shortfalls when the federal funds are gone. They will then need to develop a plan to avoid those shortfalls that considers both revenue options and spending cuts.

Other state budgeting practices can facilitate a multiyear planning approach. This includes using long-term revenue and expenditure forecasts, which could address the loss of federal funds. These, along with stress testing to gauge budget performance in different scenarios and maintaining sufficient rainy day funds and other reserves to help preserve critical public services in the event of sudden revenue losses, can help officials recognize the risk of a fiscal cliff and give them time to avoid it.

STATE REPORT CARDS

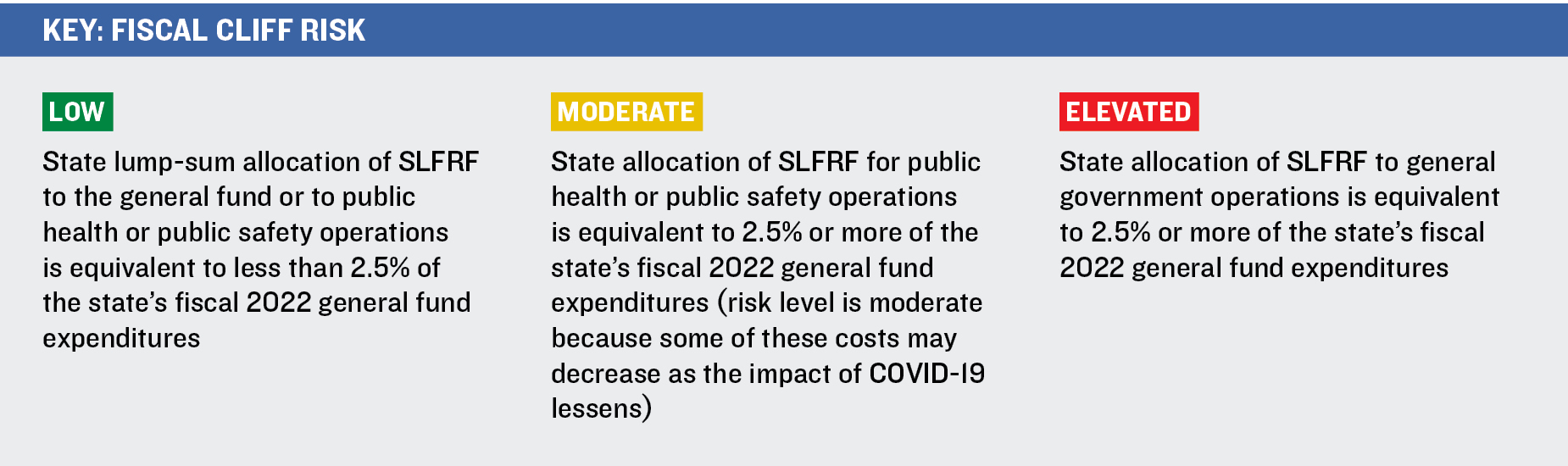

Assessment of Fiscal Cliff Risk Among the Eleven Largest States

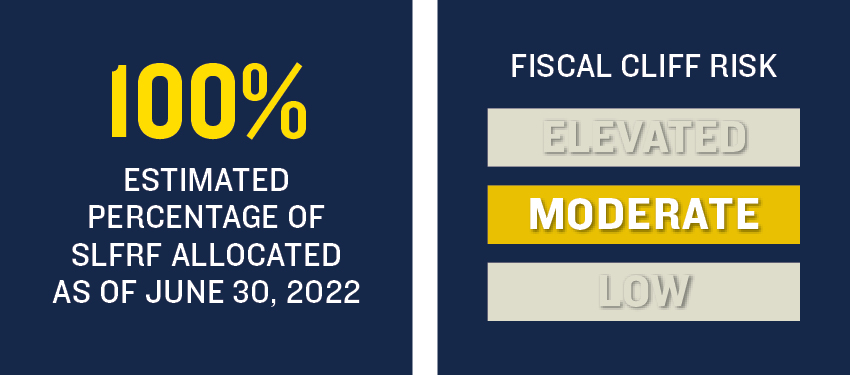

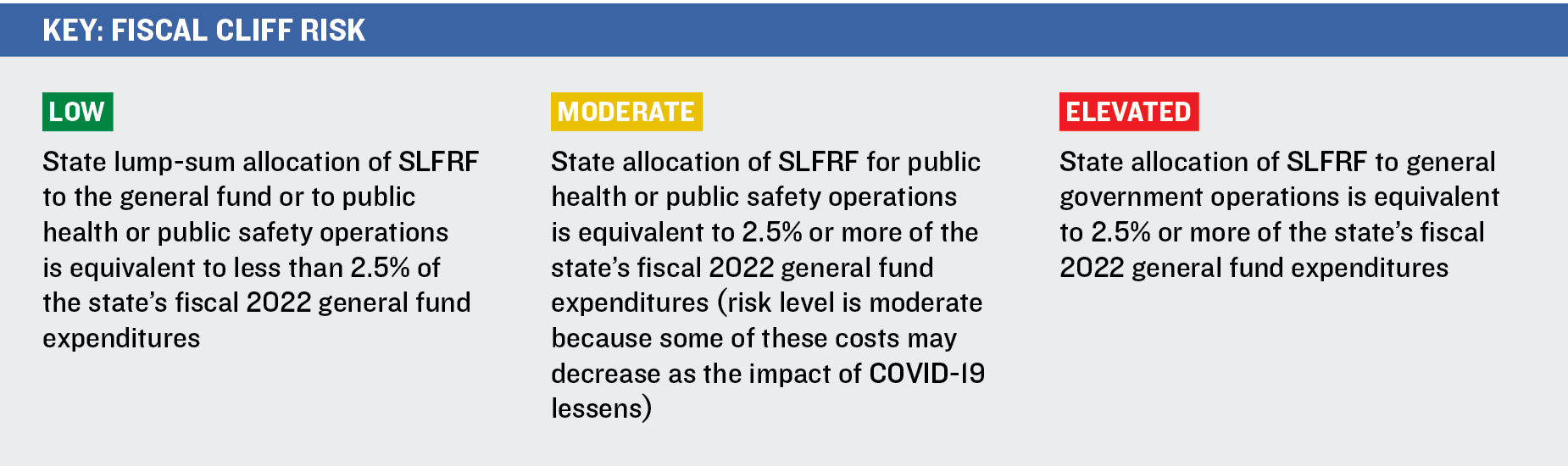

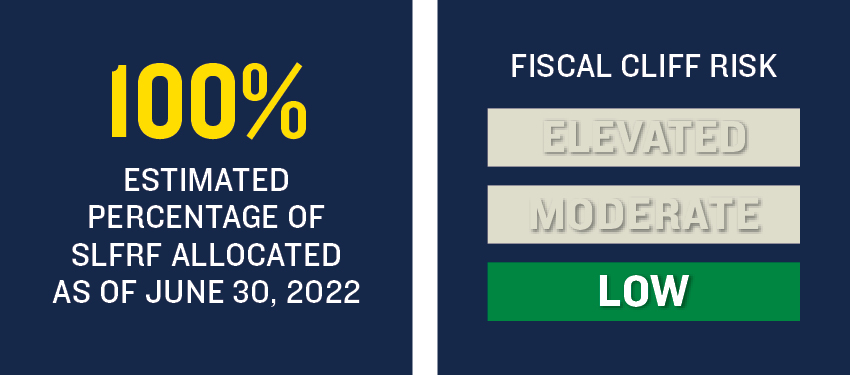

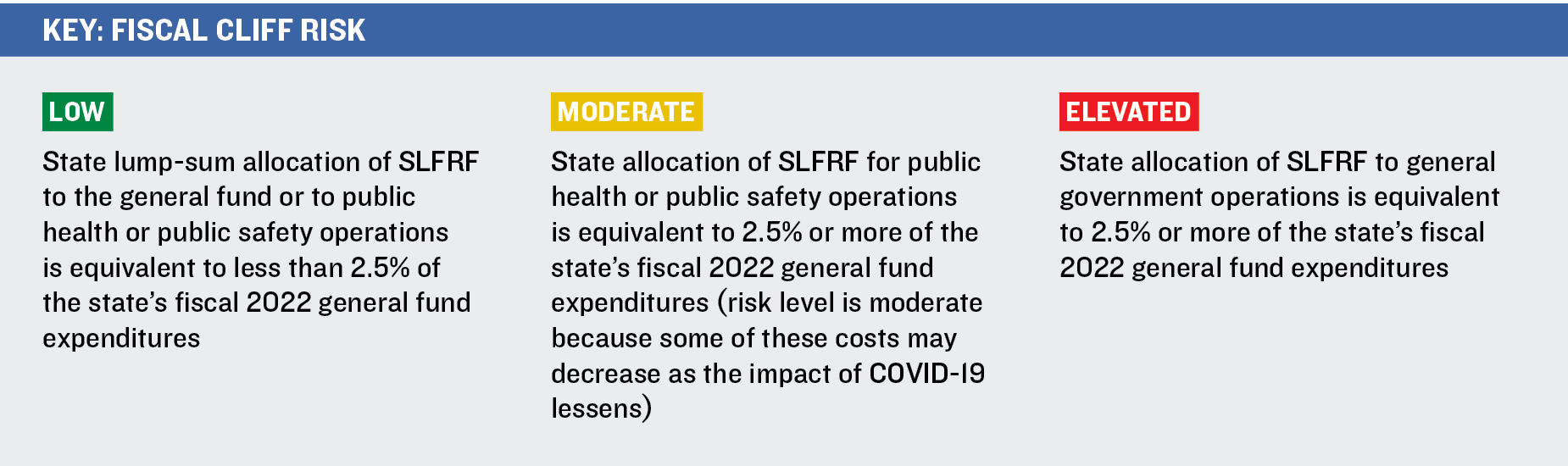

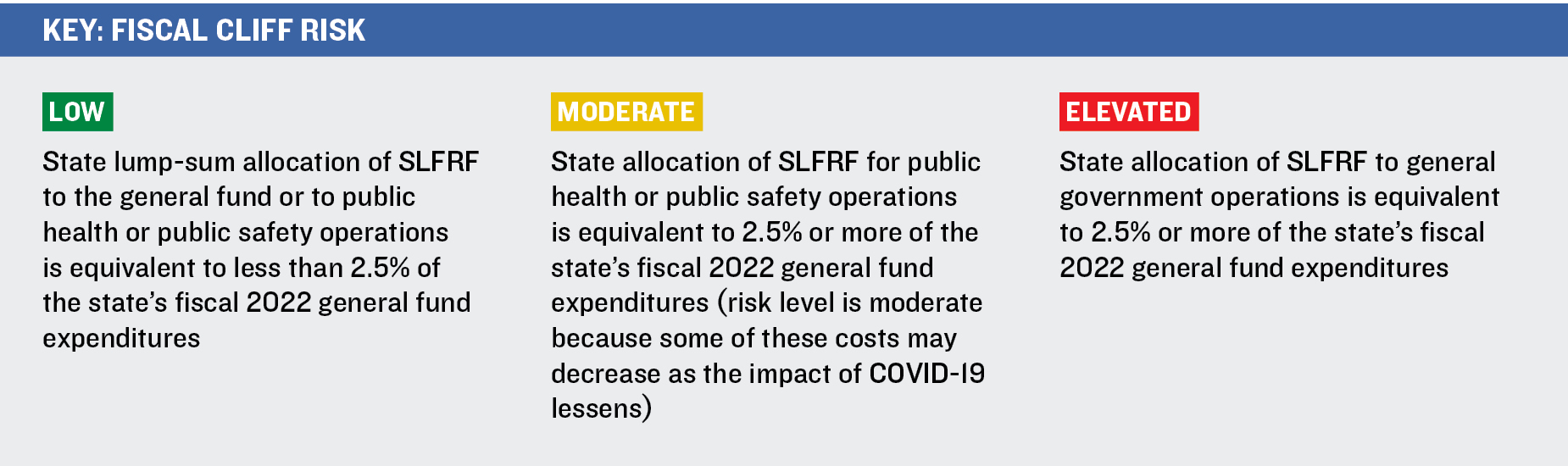

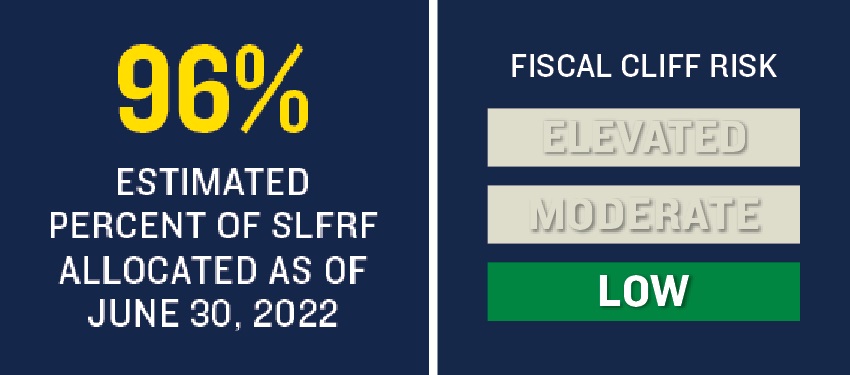

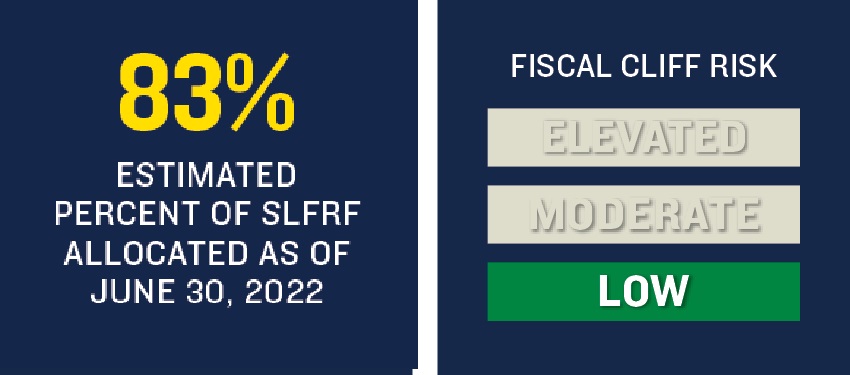

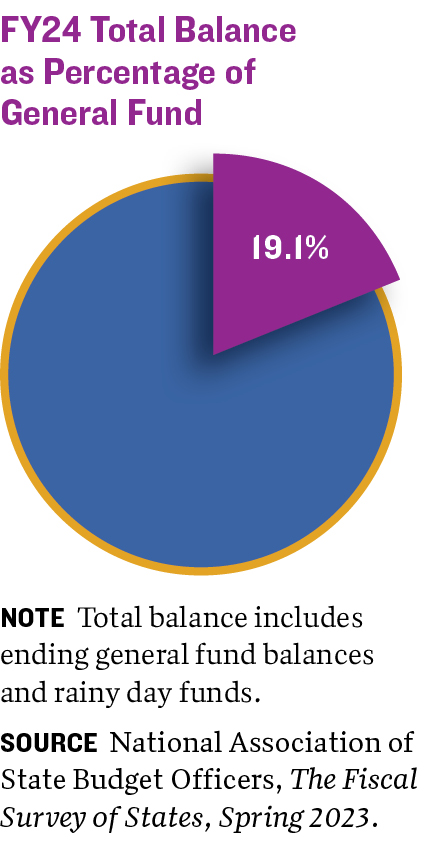

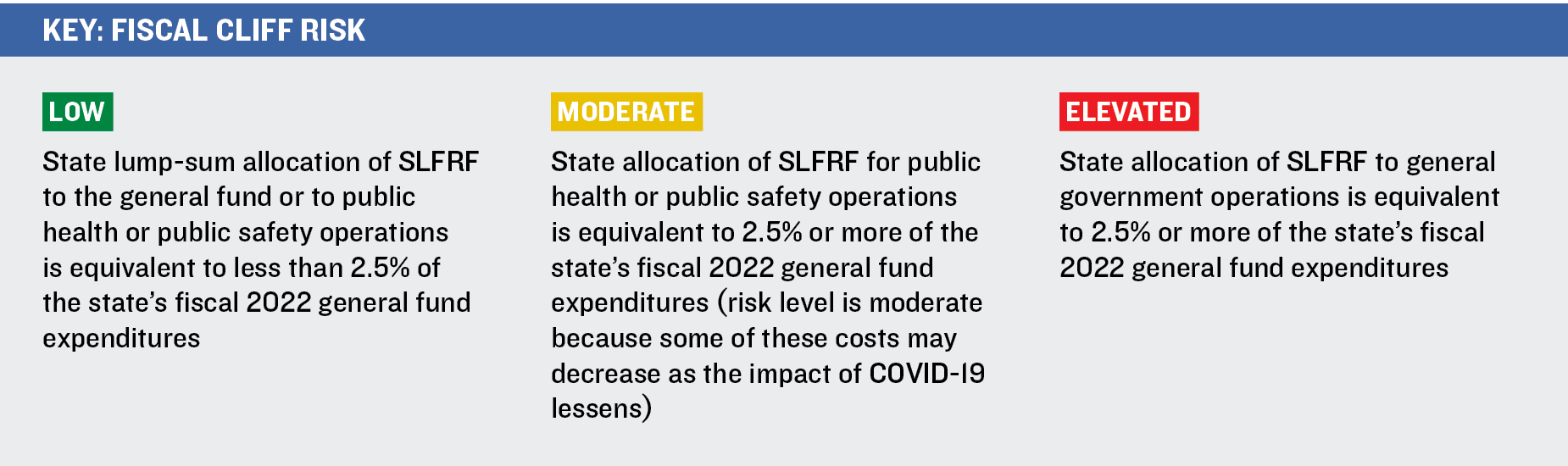

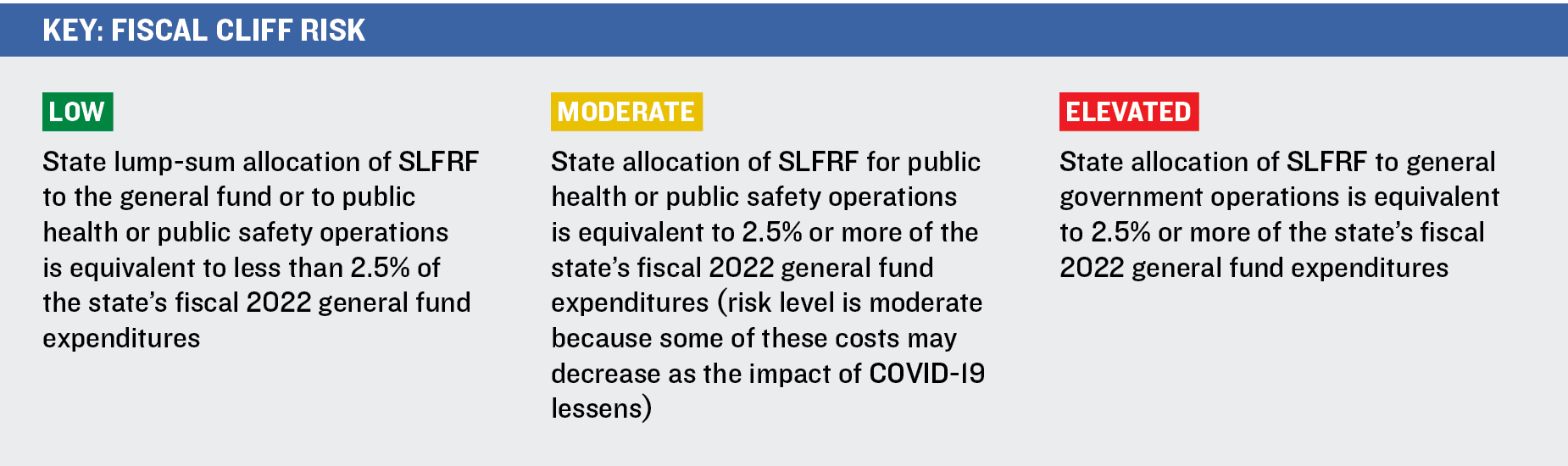

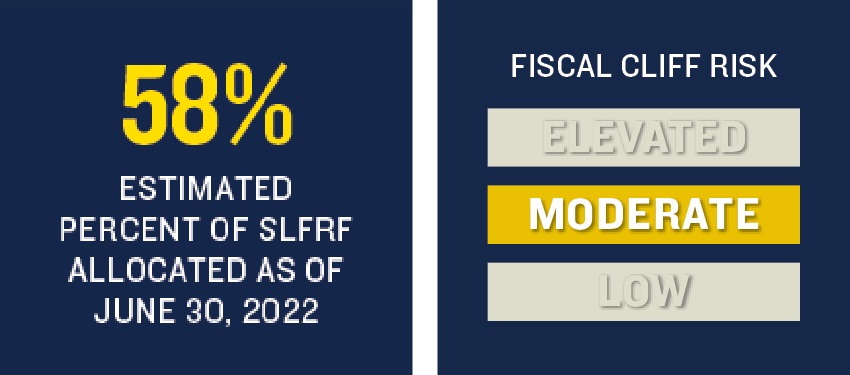

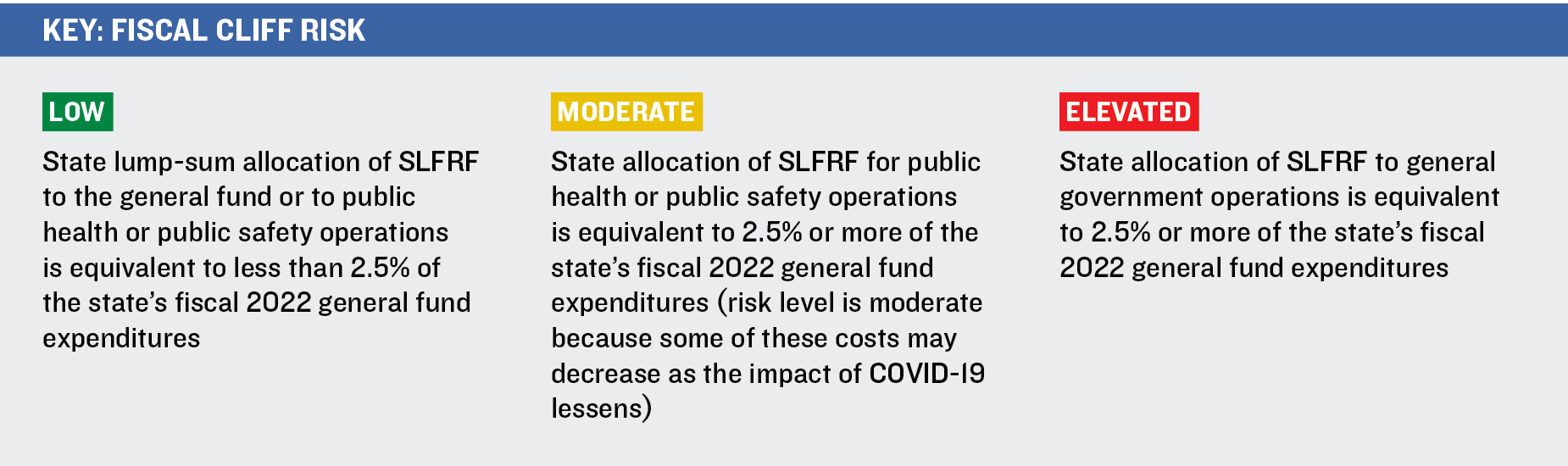

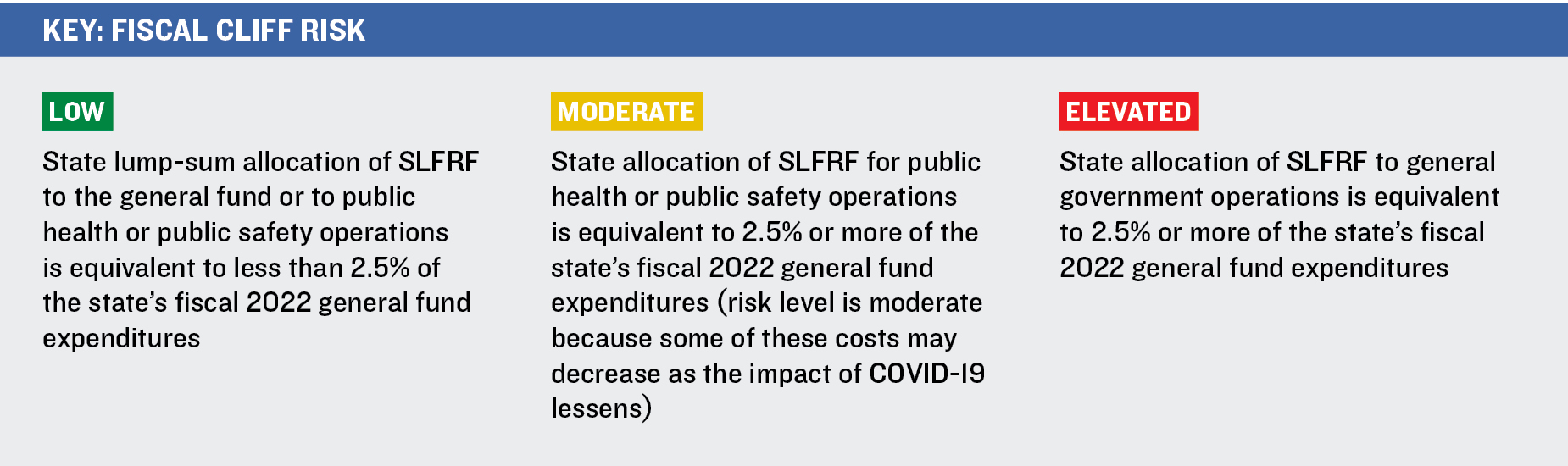

THE REPORT CARD FOR EACH STATE gauges the risks of a fiscal cliff when the SLFRF program ends. This assessment is based solely on a state’s allocation of those funds to date and does not consider its capacity to use other revenues to pay for programs that have been financed temporarily with SLFRF. States are listed, in declining order, by the percentage of SLFRF allocated as of June 30, 2022. The three categories of fiscal cliff risk are

THE REPORT CARD FOR EACH STATE gauges the risks of a fiscal cliff when the SLFRF program ends. This assessment is based solely on a state’s allocation of those funds to date and does not consider its capacity to use other revenues to pay for programs that have been financed temporarily with SLFRF. States are listed, in declining order, by the percentage of SLFRF allocated as of June 30, 2022. The three categories of fiscal cliff risk are

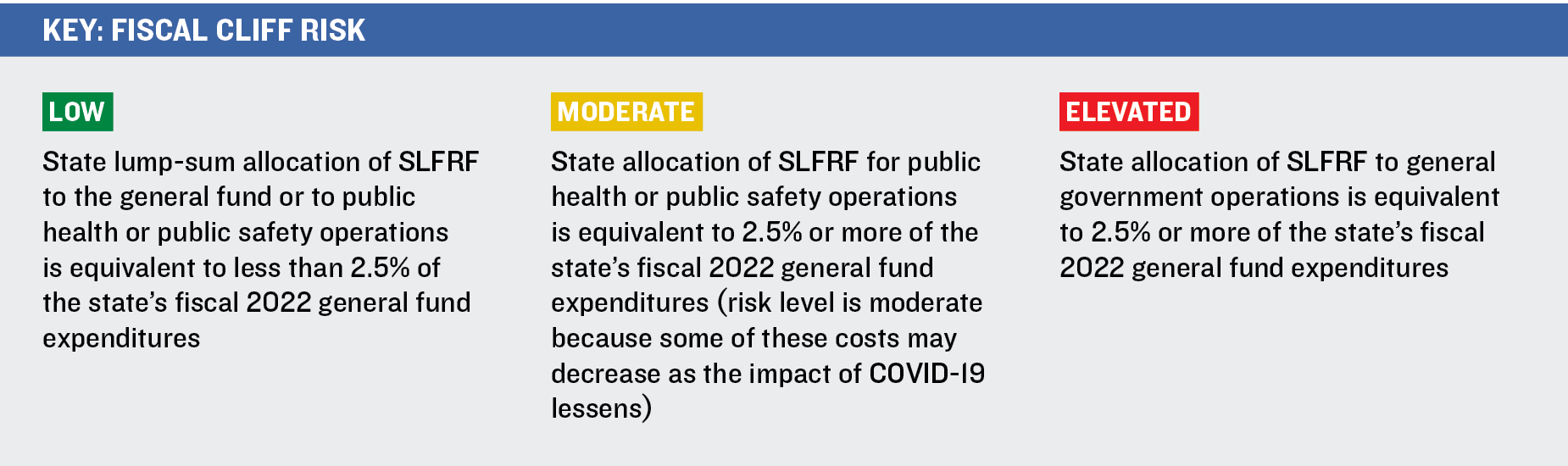

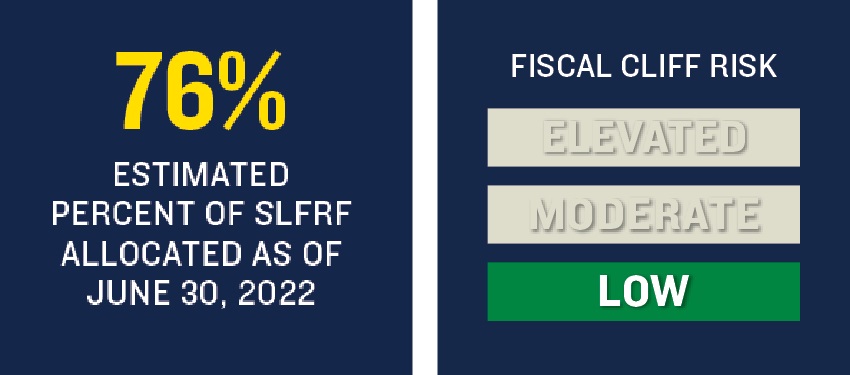

Elevated State allocation of SLFRF to general government operations is equivalent to 2.5% or more of the state’s fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures

Moderate State allocation of SLFRF for public health or public safety operations is equivalent to 2.5% or more of the state’s fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures (risk level is moderate because some of these costs may decrease as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lessons)

Low State lump-sum allocation of SLFRF to the general fund or to public health or public safety operations is equivalent to less than 2.5% of the state’s fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures

CALIFORNIA

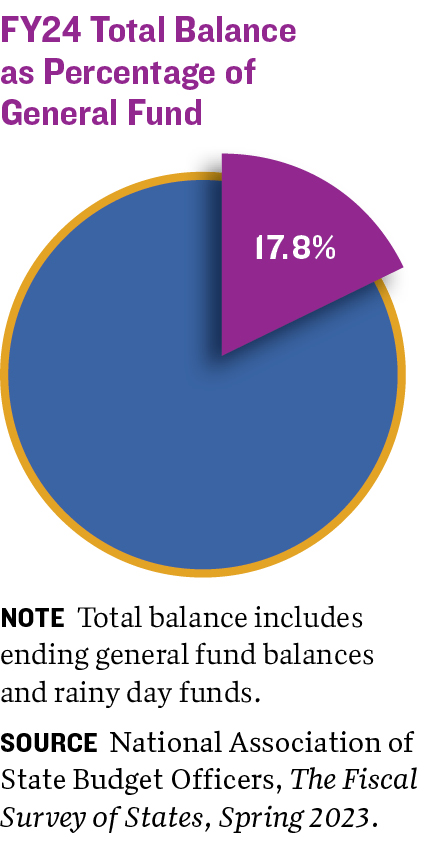

CALIFORNIA RECEIVED its $27 billion in SLFRF in one payment. Among the eleven largest states, California was the only one that had allocated almost all its SLFRF (99 percent) as of July 31, 2021. The initial allocations included $8.9 billion for the revenue replacement category, all of which was used to make a lump-sum transfer to the general fund.18 The state also had assigned large amounts to housing, infrastructure, and assistance to individuals and households.

CALIFORNIA RECEIVED its $27 billion in SLFRF in one payment. Among the eleven largest states, California was the only one that had allocated almost all its SLFRF (99 percent) as of July 31, 2021. The initial allocations included $8.9 billion for the revenue replacement category, all of which was used to make a lump-sum transfer to the general fund.18 The state also had assigned large amounts to housing, infrastructure, and assistance to individuals and households.

By 2022, the allocation to revenue replacement had risen to $13.6 billion, half the state’s total SLFRF.19 California continued to use all the funds in that category to make a lump-sum transfer into the general fund. Part of the increase in the allocation to the general fund (about $2.0 billion) was due to three programs being moved into revenue replacement.20 The California budget summary indicated that the revised revenue replacement figure also reflects an updated estimate of state revenue loss due to the pandemic ($17.2 billion) and an increase in a reserve for potential compliance risks.

According to California’s 2022 fiscal recovery plan, revenue replacement dollars are being used to restore state employee pay; fund health and human services programs, higher education, and courts; and avoid planned budget deferrals for local school districts and community colleges. The use of SLFRF for these types of recurring costs increases the risks of a fiscal cliff when the federal funds are no longer available.

California also allocated SLFRF to public health and negative economic impacts categories. Some of this money is being used to finance programs that deal with needs that may continue after the federal funding program ends—for example, grants to cities and counties for youth employment and work study opportunities ($185 million); emergency financial aid to community college students ($250 million); and a college service program ($127 million) that connects low-income students with community-based organizations that are addressing the impacts of the pandemic. When the federal funding ends, an alternative revenue source will need to be identified or the programs will need to be scaled back or eliminated.

In addition, the state is using SLFRF to invest in new or expanded community assets. The spending includes $530 million for facilities to expand behavioral health services for low-income residents, $4.7 billion for long-term housing, and $3.8 billion for broadband infrastructure. Within the housing allocation, California is investing $450 million for the acquisition, construction, and rehabilitation of care facilities for low-income adults and seniors. The state also allocated $1.75 billion for the acquisition, renovation, and repair of, as well as operating subsidies for, hotels, motels, and other property that can be used to house the homeless or those at risk of being homeless. The entities that own these assets will need to have sufficient funds to pay for the associated operation and maintenance costs on an ongoing basis. From the state’s perspective, the demand for these types of assets are likely to continue beyond the end of the SLFRF program.

ILLINOIS

ILLINOIS RECEIVED $8.1 billion in SLFRF in one payment. The state appropriated $2.8 billion from its SLFRF and Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund dollars in the fiscal 2022 budget. This included $1 billion for water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure and $1.8 billion for operational programs.21 The state also authorized $2.0 billion in SLFRF as reserves for transfers into the general fund. The actual SLFRF reserve amount spent in fiscal 2022 was $736 million, and $764 million was expected to be spent in 2023.22

ILLINOIS RECEIVED $8.1 billion in SLFRF in one payment. The state appropriated $2.8 billion from its SLFRF and Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund dollars in the fiscal 2022 budget. This included $1 billion for water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure and $1.8 billion for operational programs.21 The state also authorized $2.0 billion in SLFRF as reserves for transfers into the general fund. The actual SLFRF reserve amount spent in fiscal 2022 was $736 million, and $764 million was expected to be spent in 2023.22

In March 2022, the Illinois legislature authorized the use of $2.7 billion in SLFRF to repay a portion of the state’s federal loans for its unemployment trust fund.23 This is a one-time cost that does not increase the risk of a fiscal cliff. The infrastructure projects authorized in Illinois’s fiscal 2022 budget are also primarily one-time costs, although grant recipients will need to pay for the operations and maintenance of the capital assets.

As of June 2022, Illinois had allocated $3.2 billion in revenue replacement funds to pay for public safety and education agency operational expenses that had increased because of COVID-19.24 If those costs continue beyond the time when federal funds are available, the state will need to identify other funding sources or scale back operations.

During fiscal 2022 and 2023, Illinois used own-source funds for one-time purposes, such as early repayment of a $2 billion loan from the Federal Reserve’s Municipal Liquidity Facility, which was authorized under the CARES Act; $2.5 billion to repay the state’s overdue

bills; an extra $500 million contribution to the state’s pension funds; and a $1 billion transfer to the Budget Stabilization Fund, the state’s rainy day fund.25 These actions may have been due in part to SLFRF freeing up state revenues for other purposes. This suggests that the state may have state revenues available in the future to pay at least some of the operating costs that were temporarily financed with SLFRF.

In contrast, Illinois is also applying SLFRF to some programs that appear to address recurring needs. This includes funding for community violence prevention and interruption programs ($70 million), housing support ($28 million), mental health crisis services ($50 million), and assistance to immigrants ($80 million). The state also is using SLFRF to provide support for hospitals and their workers ($218 million).

Other uses of SLFRF by the state appear to be short term in nature. This includes $300 million to assist small businesses, $30 million for the tourism industry, and $30 million for convention centers.

NORTH CAROLINA

IN NOVEMBER 2021, the governor signed the fiscal 2023 biennial budget, which appropriated all the state’s federal relief funds ($5.4 billion).26 North Carolina allocated $3.1 billion to revenue replacement, which accounts for 57 percent of all its SLFRF. Some of the larger programs in this category address one-time spending, such as

IN NOVEMBER 2021, the governor signed the fiscal 2023 biennial budget, which appropriated all the state’s federal relief funds ($5.4 billion).26 North Carolina allocated $3.1 billion to revenue replacement, which accounts for 57 percent of all its SLFRF. Some of the larger programs in this category address one-time spending, such as  premium pay for state employees and local education employees ($545 million) and for health care workers ($133 million), multifamily housing ($170 million), asbestos removal at schools and day care facilities ($150 million), and water and sewer projects at state parks ($40 million).

premium pay for state employees and local education employees ($545 million) and for health care workers ($133 million), multifamily housing ($170 million), asbestos removal at schools and day care facilities ($150 million), and water and sewer projects at state parks ($40 million).

Other SLFRF allocations under the revenue replacement category support state operating costs. This includes payment for COVID-19-related expenditures, such as medical costs at prisons ($45 million), reimbursement of the state health plan for pandemic-related expenditures ($101 million), continuity of state operations ($25 million), and operations of the state legislature ($22 million). Other programs are addressing state or community needs that may extend beyond 2026, such as postsecondary learning and career preparation ($97 million) and local government neighborhood revitalization and community development ($50 million).

North Carolina is also trying to help improve the fiscal condition of targeted entities. It has allocated $456 million in SLFRF to the Viable Utility Reserve program, which aims to better position distressed water and sewer utilities for the future. The state has authorized $80 million to help stabilize community college budgets.

The state’s investments in the other expenditure categories appear to focus on one-time spending. This includes $1.2 billion for water and wastewater, $663 million for broadband, and $495 million for grants and loans to businesses that suffered financial hardships because of the pandemic.

PENNSYLVANIA

PENNSYLVANIA RECEIVED $7.3 billion in SLFRF in one payment. The state has appropriated all of its SLFRF, including $6.1 billion for use in fiscal 2022 and $1.2 billion in 2023. Its 2022 fiscal recovery plan included a list of all the programs and projects, along with the allocated SLFRF. At the time it was prepared, however, state officials had not assigned an expenditure category to projects totaling $2.1 billion.27

PENNSYLVANIA RECEIVED $7.3 billion in SLFRF in one payment. The state has appropriated all of its SLFRF, including $6.1 billion for use in fiscal 2022 and $1.2 billion in 2023. Its 2022 fiscal recovery plan included a list of all the programs and projects, along with the allocated SLFRF. At the time it was prepared, however, state officials had not assigned an expenditure category to projects totaling $2.1 billion.27

Pennsylvania allocated $4.6 billion of its SLFRF (90 percent of the total) to revenue replacement. The state authorized transferring $3.8 billion of the allocation to the general fund to continue government operations in fiscal 2023. Its state fiscal recovery plan does not specify how the $3.8 billion transfer was to be used but includes a description of major increases in the 2023 general fund budget. These comprise a $1.5 billion increase to the Department of Human Services, which oversees the state’s Medicaid program, and a significant boost in the budget for the Department of Education, including an additional $525 million for the fair funding formula for schools and $225 million for a “Level Up” equity.

Pennsylvania also used revenue replacement dollars for job creation and retention programs, investments in hard-hit industries, and funds for future flexibility (expenditures totaling $407 million); highway and safety improvements ($279 million); housing construction ($50 million); and grants to emergency medical service (EMS) providers ($5 million). Some of these uses, such as the job creation and retention program and EMS grants, address needs that are likely to continue after SLFRF expires.

In addition, $50 million went to the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education “to strengthen the system’s universities and reimagine how it delivers the high-quality services its students deserve.”28 The plan did not specify whether these funds would be used for recurring operating costs or for one-time capital projects that may have future operation and maintenance costs. Health care needs were also targeted, with the state earmarking $282 million for improvements to indoor air systems and financial assistance for nursing facilities and assisted living and personal care homes;29 $25 million for assistance to EMS companies; and $210 million for recruitment and retention payments for hospital and health care workforces.

In addition, $50 million went to the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education “to strengthen the system’s universities and reimagine how it delivers the high-quality services its students deserve.”28 The plan did not specify whether these funds would be used for recurring operating costs or for one-time capital projects that may have future operation and maintenance costs. Health care needs were also targeted, with the state earmarking $282 million for improvements to indoor air systems and financial assistance for nursing facilities and assisted living and personal care homes;29 $25 million for assistance to EMS companies; and $210 million for recruitment and retention payments for hospital and health care workforces.

Among the $2.1 billion in programs that were still in the development stage, some appeared to be addressing recurring needs. These include local law enforcement support ($135 million), gun violence investigation and prosecution ($50 million), violence intervention and prevention ($75 million), higher education ($125 million), and mental health programs ($100 million). When federal funds expire, the state may need to discontinue this spending or fund these programs with other revenue sources.

FLORIDA

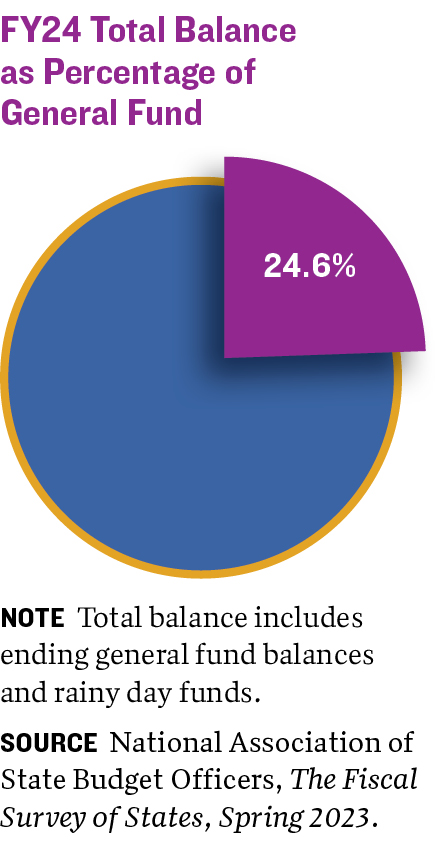

AS OF JULY 2021, Florida had allocated half ($4.4 billion) of its SLFRF, with most of that going toward water infrastructure, highways, capital facilities, and deferred maintenance. The allocation of the second half of funds reflects similar investments. As of June 2022, the state had allocated 96 percent of its $8.8 billion SLFRF grant.30

AS OF JULY 2021, Florida had allocated half ($4.4 billion) of its SLFRF, with most of that going toward water infrastructure, highways, capital facilities, and deferred maintenance. The allocation of the second half of funds reflects similar investments. As of June 2022, the state had allocated 96 percent of its $8.8 billion SLFRF grant.30

Florida is investing significant portions of SLFRF in capital projects, including $2.3 billion for water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure and about $2.9 billion of revenue replacement funds for other capital purposes. The latter amount covers $1.75 billion for state highway system projects, $50 million for county roads, $700 million for higher education capital projects, $283 million for K–12 capital projects, and $115 million for renovations to the state Capitol. Florida also allocated $844 million for higher education deferred maintenance and $350 million for a state agency deferred maintenance program. The investment in deferred maintenance may help decrease maintenance costs in the future.

The state’s fiscal recovery plan indicates that the transportation funds will be used for highway projects that had been deferred or eliminated because of the pandemic. To the extent this involves building new roads or expanding existing ones, the state will need to allocate funds for future operations and maintenance costs. Similarly, if the higher education and K–12 projects involve new or expanded facilities, the respective universities and schools will need to identify revenues to fund the operations and maintenance costs.

In addition, Florida is using SLFRF to fund the New Worlds Reading Initiative, which delivers books monthly to K–5 students who show substantial deficiency in reading.31 The program is funded with $125 million in SLFRF and $75 million in state funds. This program will either need to be scaled back when federal funds are no longer available, or the state will need to find substitute funding for the initiative.

In addition, Florida is using SLFRF to fund the New Worlds Reading Initiative, which delivers books monthly to K–5 students who show substantial deficiency in reading.31 The program is funded with $125 million in SLFRF and $75 million in state funds. This program will either need to be scaled back when federal funds are no longer available, or the state will need to find substitute funding for the initiative.

Most of Florida’s other SLFRF-financed programs provided short-term financial assistance to entities, communities, or individuals affected by the pandemic. This included $100 million in grants for job training, $175 million for local support grants, $250 million for port operation grants, and $25 million for the tourism industry.

The state is using SLFRF for other one-time purposes, including $200 million to offset revenues lost due to a temporary 25.3-cents-per-gallon reduction in the state’s motor fuel tax in October 2022. Florida is also investing in system enhancements, such as $250 million for upgrades to the workforce information system and $56 million for improvements to the reemployment assistance systems.

NEW JERSEY

AS OF JUNE 2022, New Jersey had allocated about $5.1 billion (83 percent) of its total SLFRF grant of $6.2 billion. This included $2.1 billion that was approved as part of the fiscal 2023 budget, but a breakdown of those funds was not in the 2022 New Jersey fiscal recovery plan.32

AS OF JUNE 2022, New Jersey had allocated about $5.1 billion (83 percent) of its total SLFRF grant of $6.2 billion. This included $2.1 billion that was approved as part of the fiscal 2023 budget, but a breakdown of those funds was not in the 2022 New Jersey fiscal recovery plan.32

The category with the largest allocation (about 63 percent) is negative economic impacts. One of the state’s largest investments in that category is $604 million to provide an additional year of special education to students with disabilities who otherwise would have been too old to qualify. The fiscal plan indicates that this program addressed a one-year loss in development stemming from the pandemic. Although the program was designed to be short term, the demand for expanded special education programs may continue beyond the availability of SLFRF.

Most other spending under the negative economic impacts category was short-term assistance for individuals and businesses. This included $125 million for small businesses; $808 million for rental and utility assistance and legal services to prevent eviction and homelessness; and $100 million for childcare, including recruitment and retention of staff, longer-term oversight improvements, and facility improvements.

In the public health category, New Jersey used SLFRF to strengthen emergency preparedness infrastructure at Level 1 Trauma Centers ($546 million) and hospitals ($46 million). The latter amount included an expansion of behavioral health capacity at hospitals.

These projects may require funding sources to pay for additional maintenance and operations costs, if applicable. The public health category also included funds for heating, air-conditioning, and water systems in schools and small businesses ($183 million).

Other spending categories accounted for smaller SLFRF allocations. New Jersey invested about $70 million in stormwater and other water infrastructure projects. In the revenue replacement and public sector capacity categories, New Jersey designated $40 million for affordable housing projects, $10 million to upgrade unemployment processing, and $9 million for poll workers’ wages to improve voting access.

The fiscal 2023 budget primarily included SLFRF allocations for one-time or short-term spending. Among the largest allocations are affordable housing ($305 million), capital spending needs at Rutgers University ($300 million), water infrastructure ($300 million), residential lead paint remediation ($170 million), and universal pre-K facilities ($120 million).33 Some of these projects are likely to have continuing operations and maintenance costs not covered by SLFRF.

TEXAS

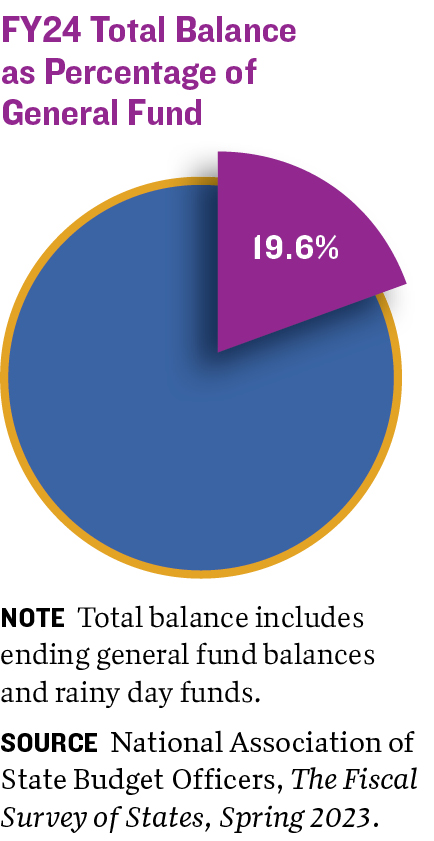

AS OF JUNE 2022, Texas had allocated about three-fourths of its $15.8 billion in SLFRF. About 58 percent ($7 billion) went to repay the state’s federal unemployment trust fund loans and replenish the fund’s capital to the statutory minimum. Texas also assigned $378 million for aid to impacted industries and to two other expenditure categories, including revenue replacement ($2.3 billion) and public health ($2.3 billion).34

AS OF JUNE 2022, Texas had allocated about three-fourths of its $15.8 billion in SLFRF. About 58 percent ($7 billion) went to repay the state’s federal unemployment trust fund loans and replenish the fund’s capital to the statutory minimum. Texas also assigned $378 million for aid to impacted industries and to two other expenditure categories, including revenue replacement ($2.3 billion) and public health ($2.3 billion).34

Texas is using a portion of its revenue replacement allocation to pay for recurring costs, including funding for state employee compensation costs at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice ($360 million) and operations at the University of Houston ($50 million). The state is investing $150 million of SLFRF in the deployment and operations of the Next Generation 9-1-1 Service. The state and the University of Houston will need to identify alternative funding sources for these purposes after the SLFRF program ends.

Texas is deploying a portion of revenue replacement funds for programs addressing needs that are likely to continue beyond the duration of SLFRF. This includes funding for the Texas Child Mental Health Consortium to expand mental health services for children, pregnant women, and postpartum women ($113 million); for higher education to assist high-risk students ($20 million) and provide incentives for students to finish degrees ($15 million); for EMS workers, especially in rural and underserved areas ($22 million); and for the state sexual assault prevention program ($52 million) and crime victims compensation program ($55 million).

To avoid pandemic-related insurance premium increases for teachers and retired teachers, the state designated $286 million to cover COVID-19-related health claims for the Teacher Retirement System. If there is a continuing need for these programs after the SLFRF expires, the state may feel pressure to find alternative revenues.

Another use of revenue replacement funds that will probably result in future recurring costs is building or expanding facilities. This includes $300 million for a new emergency operations center, $238 million for a state psychiatric hospital in Dallas, and $40 million for a behavioral health center in West Texas’s oil-rich Permian Basin. These facilities are likely to require future funding for operations and maintenance.

Texas also allocated $2 billion under the public health category to finance contract nurses at understaffed hospitals and other health care facilities and to operate regional antibody-infusion centers to provide therapeutic drugs to COVID-19 patients who do not require hospitalization. These programs address health care needs that may continue beyond the availability of federal funds.

OHIO

Ohio had appropriated approximately $3.5 billion in SLFRF as of June 2022—about 65 percent of its allocation of $5.4 billion. The Ohio 2022 fiscal recovery plan states that using one-time funds for one-time purposes will help ensure future stability.35

Ohio had appropriated approximately $3.5 billion in SLFRF as of June 2022—about 65 percent of its allocation of $5.4 billion. The Ohio 2022 fiscal recovery plan states that using one-time funds for one-time purposes will help ensure future stability.35

About four-fifths of the state’s SLFRF grant went toward one-time uses. This included a $1.5 billion repayment of unemployment trust fund loans, which the state said would obviate the need for an unemployment tax increase and would allow firms to invest and hire more workers. Ohio designated $250 million for water and wastewater projects and $45 million for dredge material processing facilities for Lake Erie. Under the revenue replacement category, the state funded a meat processor grant program with $18 million to help strengthen the industry supply chain.

Ohio is also using SLFRF for projects or programs that may have continuing demand after those funds are no longer available. These include investing $250 million in antiviolence programs and $84 million in capital projects to expand pediatric behavioral health capacity.

In addition, $5 million under the public sector capacity category went to rehire state employees at the Ohio Expositions Commission. The state may need to scale back staffing or identify alternative funds to pay those workers after the SLFRF program expires.

In June 2022, Ohio enacted H.B. 687, which included about $1.3 billion in SLFRF appropriations. While these projects are encompassed in the $3.5 billion SLFRF appropriations cited in the state’s 2022 fiscal recovery plan, specific projects were not identified in the plan itself. Information available on these projects through a tracking system developed by the Ohio Poverty Law Center suggests that the state authorized SLFRF for one-time projects such as water and wastewater ($451 million) and parks and trails ($152 million). It also appropriated SLFRF for the Appalachian Community Grants Program ($500 million) to help encourage regional economic growth,36 which may require alternative funding in the future.

MICHIGAN

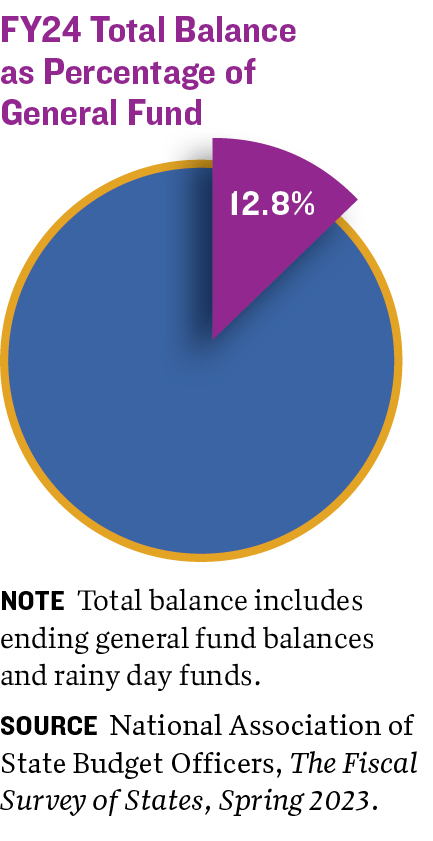

MICHIGAN HAD ALLOCATED only about 7 percent of its SLFRF as of July 31, 2021. A year later, however, 58 percent of its $6.5 billion SLFRF authorization had been assigned. The state appropriated additional funds in July 2022. Those projects were not included in the state’s 2022 fiscal recovery plan but were considered in our assessment of the state.37

MICHIGAN HAD ALLOCATED only about 7 percent of its SLFRF as of July 31, 2021. A year later, however, 58 percent of its $6.5 billion SLFRF authorization had been assigned. The state appropriated additional funds in July 2022. Those projects were not included in the state’s 2022 fiscal recovery plan but were considered in our assessment of the state.37

The largest SLFRF allocations included $1.3 billion for water and wastewater projects and $1.3 billion for negative economic impacts. The latter included programs providing financial assistance to businesses ($409 million), pandemic-impacted industries ($160 million), and long-term care facilities ($100 million). The state authorized almost $150 million for housing in the negative impacts category.

Among the eleven largest states, Michigan is the only one to identify in its fiscal recovery plan principles and metrics to guide allocation of the funds. One principle specifically speaks to sustainability. It asks how sustainable the proposal is, if it will require ongoing support, and its potential return on investment.38 The principles also deal with such issues as whether a project or program addresses needs created by the pandemic; inequities; opportunities for social change; leveraging of other resources; and the effectiveness of a program, as well as the capacity and support for it.

According to its 2022 fiscal recovery plan, the state had not yet appropriated any SLFRF to revenue replacement as of June 30, 2022. But that changed soon after. A monthly COVID-19 expenditure report for August 2022 showed $883 million in revenue replacement money allocated to the Department of Corrections.39 If these funds are being used to cover recurring operating costs, Michigan may encounter a fiscal cliff without sufficient alternative revenues when the federal funds are no longer available.

According to its 2022 fiscal recovery plan, the state had not yet appropriated any SLFRF to revenue replacement as of June 30, 2022. But that changed soon after. A monthly COVID-19 expenditure report for August 2022 showed $883 million in revenue replacement money allocated to the Department of Corrections.39 If these funds are being used to cover recurring operating costs, Michigan may encounter a fiscal cliff without sufficient alternative revenues when the federal funds are no longer available.

Michigan also designated SLFRF to public sector capacity. This allocation includes $220 million to develop, improve, repair, and maintain state parks and trails, and $5 million to create an Office of Infrastructure, which will help with planning and applying for federal grants under the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Money for the office was provided for the period from 2022 until 2026. If the office is still needed after that, the state will need to find an alternative funding source.

Additional revenues may also be needed to support an expansion of the Great Start Readiness program for educationally disadvantaged children that was financed with SLFRF ($121 million). Michigan may face other requests to continue health care apprenticeship programs in both urban and rural areas, as well as other training initiatives, which are part of a $300 million SLFRF-funded project to recruit, retain, and train health care workers.

GEORGIA

Georgia received $4.9 billion in SLFRF in two payments. Its allocation of the funds rose from about 18 percent as of July 31, 2021, to 42 percent as of June 30, 2022. Much of the state’s allocations are focused on infrastructure and assistance to businesses and nonprofit organizations hurt by the pandemic.40

Georgia received $4.9 billion in SLFRF in two payments. Its allocation of the funds rose from about 18 percent as of July 31, 2021, to 42 percent as of June 30, 2022. Much of the state’s allocations are focused on infrastructure and assistance to businesses and nonprofit organizations hurt by the pandemic.40

The state distributed its first receipt of SLFRF primarily through grants in the areas of water and wastewater, broadband, and negative economic impacts. Georgia solicited proposals from state government agencies, local governments, for-profit entities, and nonprofit organizations. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution newspaper reported that the state received almost 1,500 applications totaling $14.6 billion, or 16 times as much as the $875 million the state had available in that round.41

The state distributed its first receipt of SLFRF primarily through grants in the areas of water and wastewater, broadband, and negative economic impacts. Georgia solicited proposals from state government agencies, local governments, for-profit entities, and nonprofit organizations. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution newspaper reported that the state received almost 1,500 applications totaling $14.6 billion, or 16 times as much as the $875 million the state had available in that round.41

As of June 2022, much of Georgia’s allocation of SLFRF was for one-time purposes. This includes $408 million for broadband, $518 million for water and sewer, $325 million for targeted industries and businesses, and $382 million for health care organizations. Other allocations include $100 million for housing grants, $100 million for premium pay for first responders, and $125 million to address a backlog in court cases.42

There may be recurring demand for some of the health care spending and for a program that uses $50 million of SLFRF to assist victim-services providers. The 2022 fiscal recovery plan says Georgia had not yet allocated funds under the revenue replacement category but would continue to monitor the economy to determine if revenue replacement aid were needed.

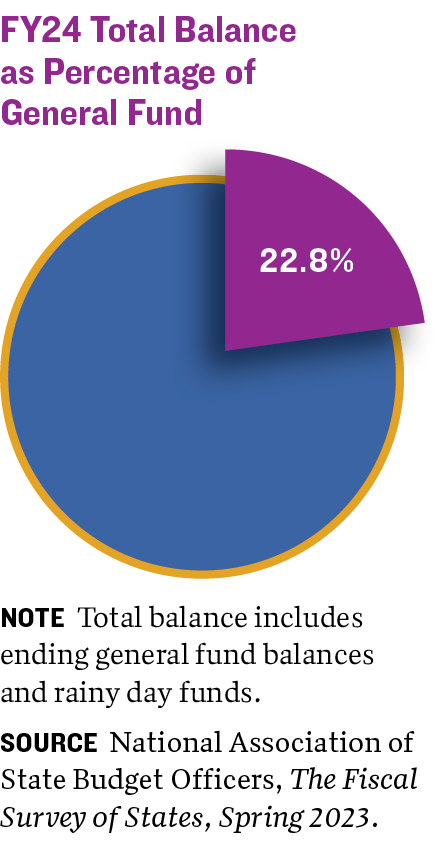

NEW YORK

NEW YORK SAID IN ITS fiscal 2022 Enacted Budget Financial Plan that it planned to spend its $12.7 billion SLFRF over four years, including $4.5 billion in fiscal 2022, $2.35 billion in fiscal 2023, $2.25 billion in fiscal 2024, and $3.65 billion in fiscal 2025.43 Spreading the funds over multiple years could help the state respond to future needs and lessen the magnitude of the drop-off when the federal funds are no longer available.

NEW YORK SAID IN ITS fiscal 2022 Enacted Budget Financial Plan that it planned to spend its $12.7 billion SLFRF over four years, including $4.5 billion in fiscal 2022, $2.35 billion in fiscal 2023, $2.25 billion in fiscal 2024, and $3.65 billion in fiscal 2025.43 Spreading the funds over multiple years could help the state respond to future needs and lessen the magnitude of the drop-off when the federal funds are no longer available.

In fiscal 2022, New York allocated $2.8 billion for the provision of government services and $968 million for the salaries of state employees substantially dedicated to public health or safety responses to the pandemic.44 The provision of government services includes state employee salaries, Social Security payments, and funds for local governments assisting with support services ($689 million) and with probation aide services ($45 million). This use of funds for such operating purposes increases the risks of a fiscal cliff.

New York’s other uses of SLFRF during fiscal 2022 targeted organizations and individuals that experienced hardships because of the pandemic. This included funding for restaurants ($24 million), small businesses ($526 million), and rental assistance ($183 million).

The state recovery plan indicates that New York planned to continue using SLFRF in fiscal 2023 to fund salaries of employees dedicated to the public health or safety pandemic responses. The state also planned to use SLFRF for an immunization program ($7 million), lead poisoning prevention ($14 million), and rural rental assistance ($22 million).

The state recovery plan indicates that New York planned to continue using SLFRF in fiscal 2023 to fund salaries of employees dedicated to the public health or safety pandemic responses. The state also planned to use SLFRF for an immunization program ($7 million), lead poisoning prevention ($14 million), and rural rental assistance ($22 million).

The state comptroller notes that an income tax surcharge on high-income earners, which was estimated to generate $3.25 billion in fiscal 2023, is scheduled to expire at the end of 2027.45 This compounds the risk associated with the expiration of SLFRF.

Another complication is the $15 billion in federal pandemic aid that was channeled to the state-owned Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA)46 under pandemic relief programs separate from SLFRF and a $2.9 billion short-term loan for the MTA from the Federal Reserve’s Municipal Liquidity Facility that matures on December 15, 2023.47 Replacing these dollars is highly likely to put additional fiscal pressure on the state.48

APPENDIX A: Overview of SLFRF State Allocations

THE TREASURY REQUIRES EACH STATE to submit an annual fiscal recovery plan that describes how it allocated its SLFRF allotment, along with related information on topics such as public engagement, equity issues, performance measurements, and evidence-based programs. Beginning with the 2022 report, state governments are required to include a project inventory as part of the fiscal recovery plan. This overview uses information from the state fiscal recovery plans submitted in July 2022.

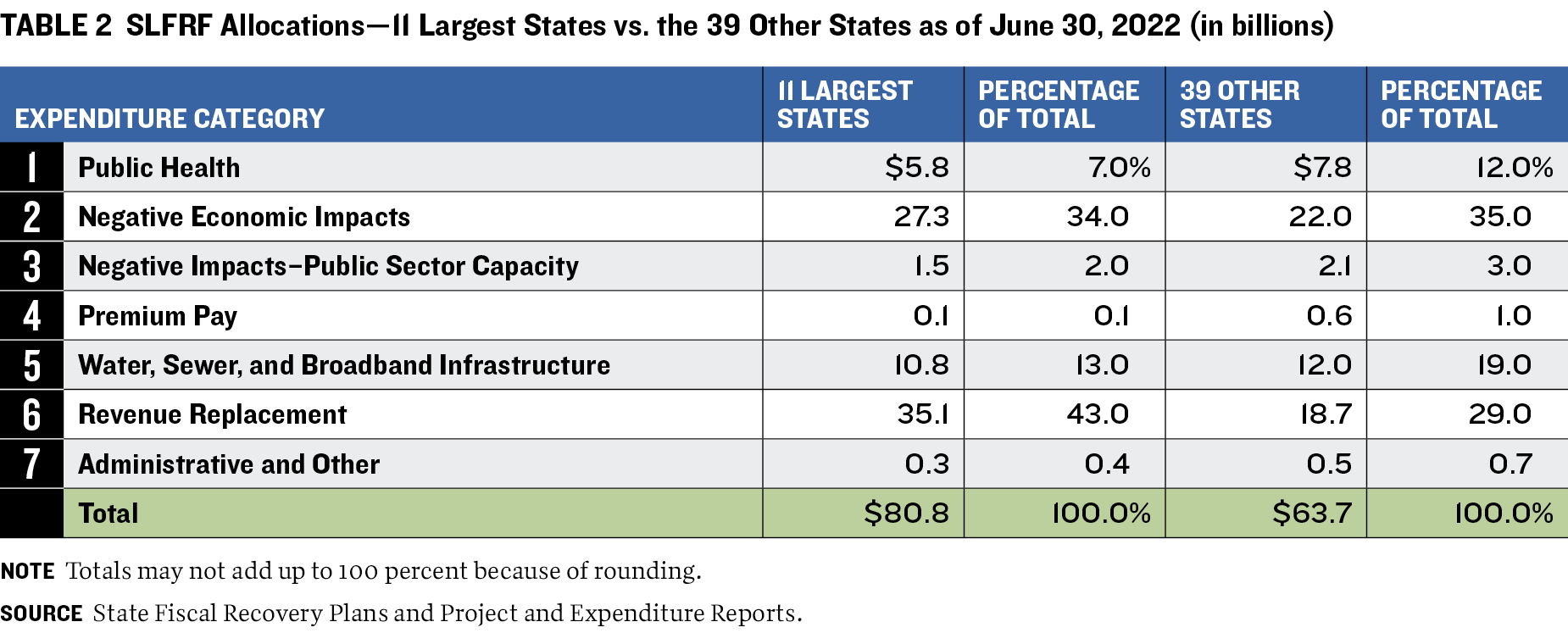

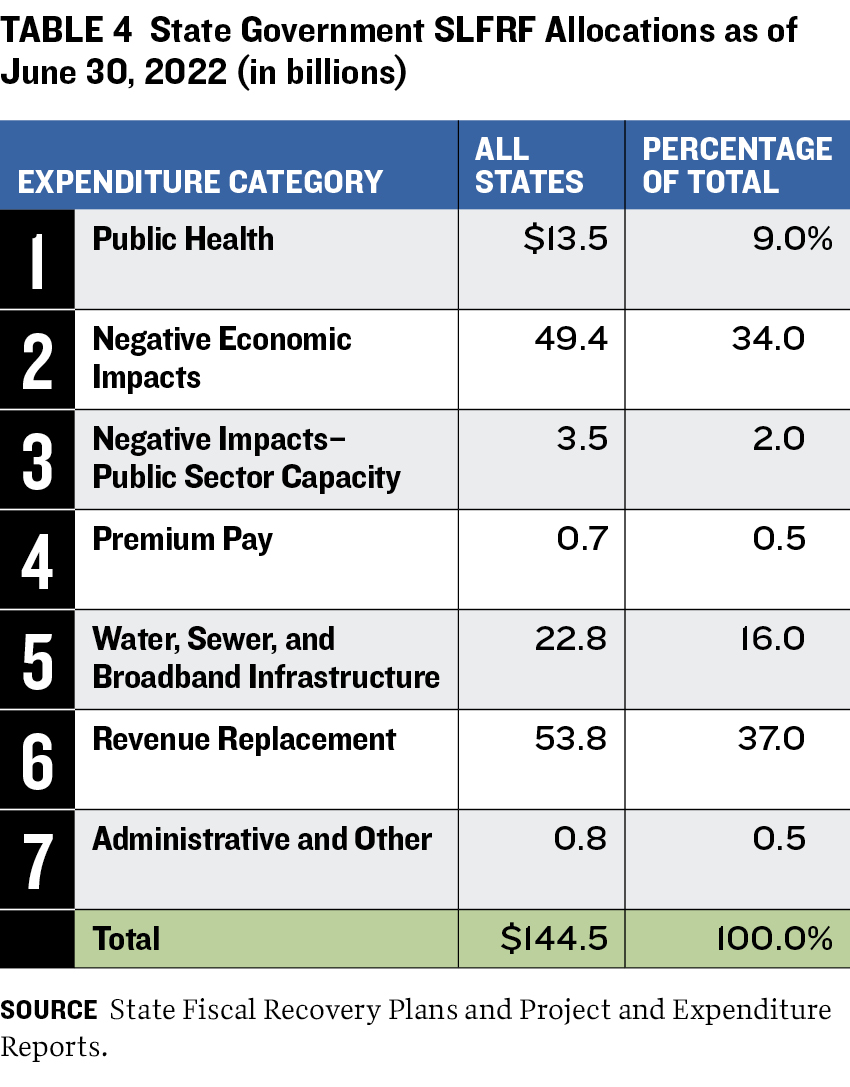

As shown in table 4, the expenditure category with the largest allocation is revenue replacement (37 percent), followed by negative economic impacts (34 percent). A portion of the latter includes repayment of federal loans to state unemployment trust funds or replenishment of the funds’ capital; such repayments and replenishments in aggregate account for 16 percent of the total SLFRF allocated. This leaves 18 percent allocated for other purposes in the negative economic impacts category, such as assistance to businesses, households, and individuals to cover costs including rent, utilities, and food.

As shown in table 4, the expenditure category with the largest allocation is revenue replacement (37 percent), followed by negative economic impacts (34 percent). A portion of the latter includes repayment of federal loans to state unemployment trust funds or replenishment of the funds’ capital; such repayments and replenishments in aggregate account for 16 percent of the total SLFRF allocated. This leaves 18 percent allocated for other purposes in the negative economic impacts category, such as assistance to businesses, households, and individuals to cover costs including rent, utilities, and food.

The next two highest totals are for water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure (16 percent) and public health (9 percent). Accounting for relatively small percentages of the total allocation are negative impacts–public sector capacity (2 percent), premium pay (0.5 percent), and administrative and other (0.5 percent).

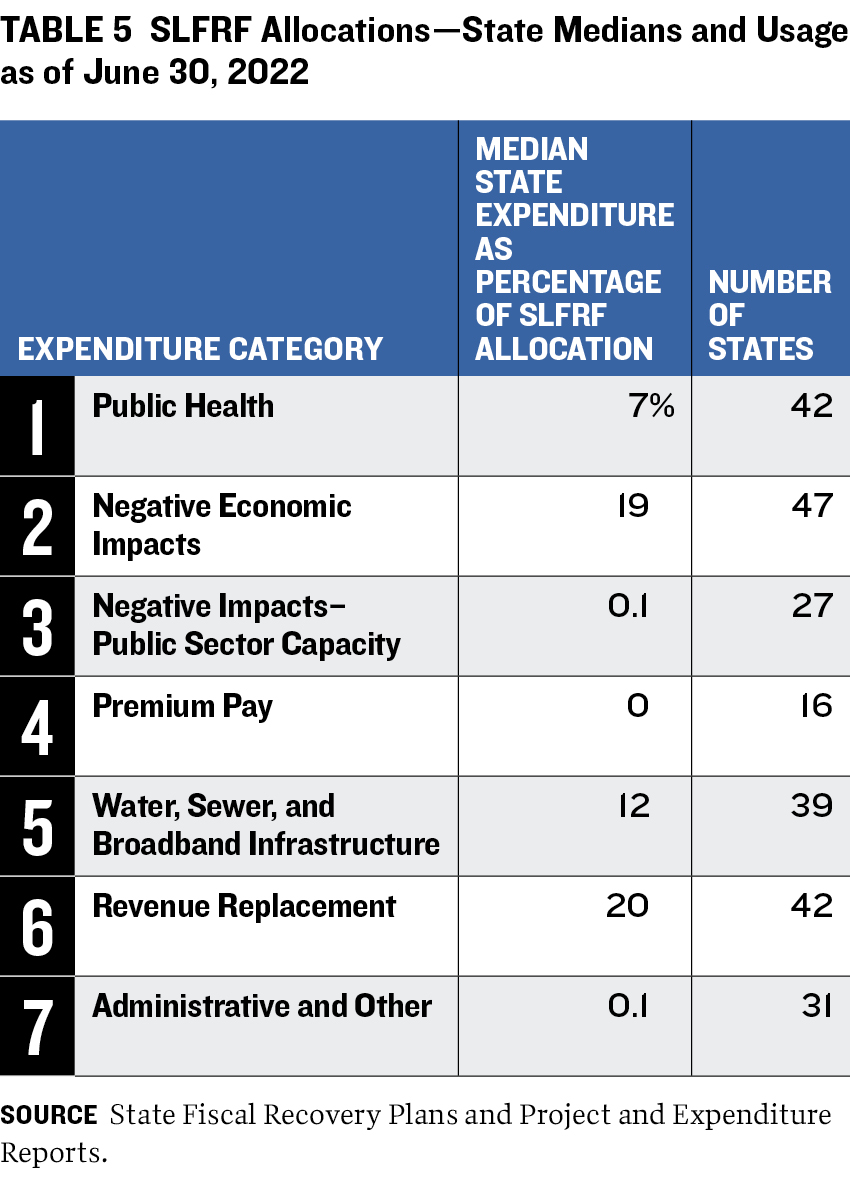

Table 5 shows the state medians for the percentage of SLFRF allocated to each spending category as of June 30, 2022. The figures are comparable to the aggregate allocation of total SLFRF, with the exception of negative economic impacts and revenue replacement. The figure for the former category is lower, since the median value is zero for the unemployment trust fund component. The state median percentage for revenue replacement is 20 percent, compared to the 37 percent according to total SLFRF allocations. This disparity is due to the larger allocations that some of the largest states are making to revenue replacement.

exception of negative economic impacts and revenue replacement. The figure for the former category is lower, since the median value is zero for the unemployment trust fund component. The state median percentage for revenue replacement is 20 percent, compared to the 37 percent according to total SLFRF allocations. This disparity is due to the larger allocations that some of the largest states are making to revenue replacement.

Most states allocated at least some SLFRF to public health (forty-two states); negative economic impacts (forty-seven); water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure (thirty-nine); and revenue replacement (forty-two). The categories the states used least use are premium pay (sixteen), public sector capacity (twenty-seven), and administrative and other (thirty-one).

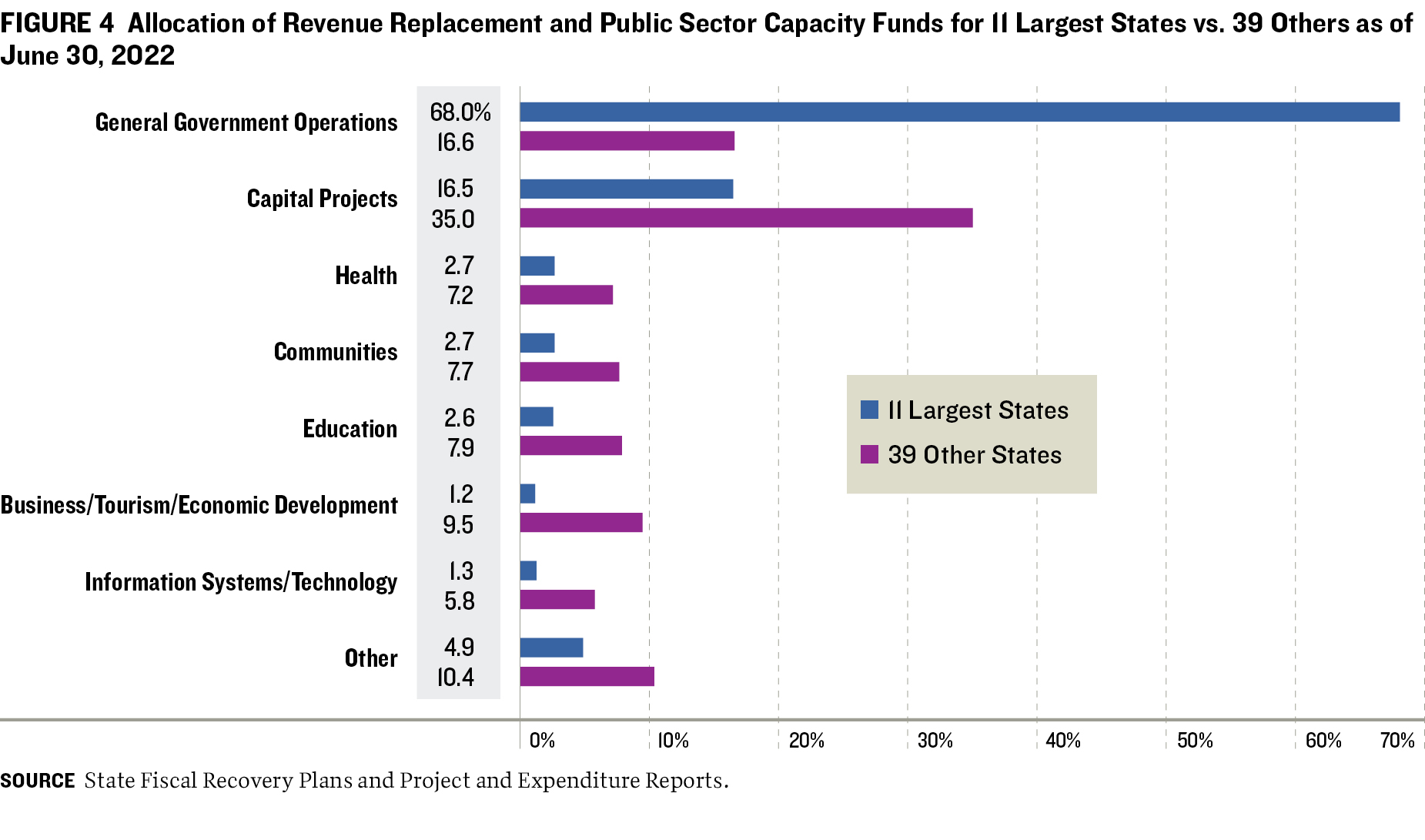

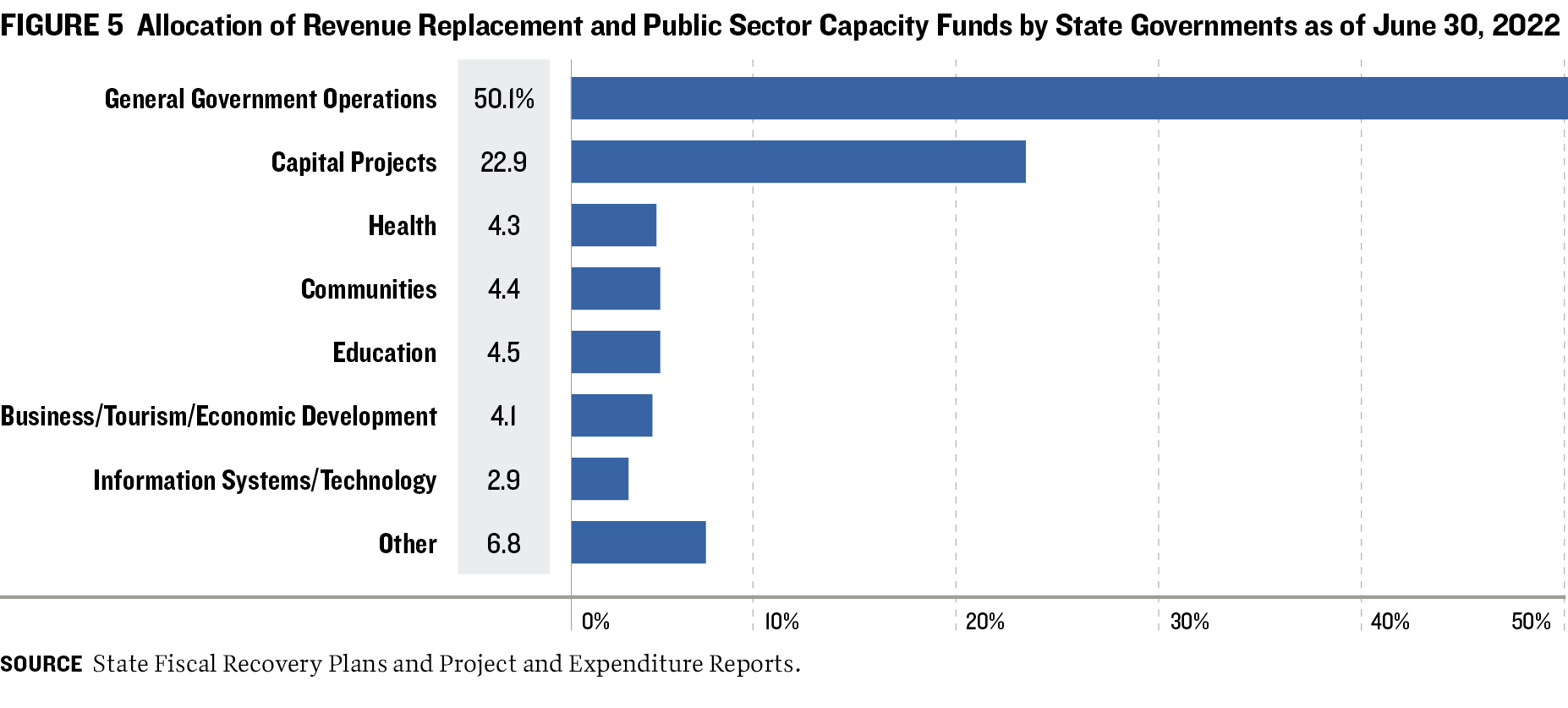

A closer look at the revenue replacement and public sector capacity categories reveals that about half the funds allocated as of June 30, 2022, went to government operations and about one-fourth (23 percent) to capital investments (figure 5).49 About half of the capital projects were in transportation, with roads accounting for about three-fourths of that. Another major capital project use was for state facilities, including universities. One state, Alabama, is using $400 million of its SLFRF for prison construction, including enhanced health care and vocational and rehabilitative services.50

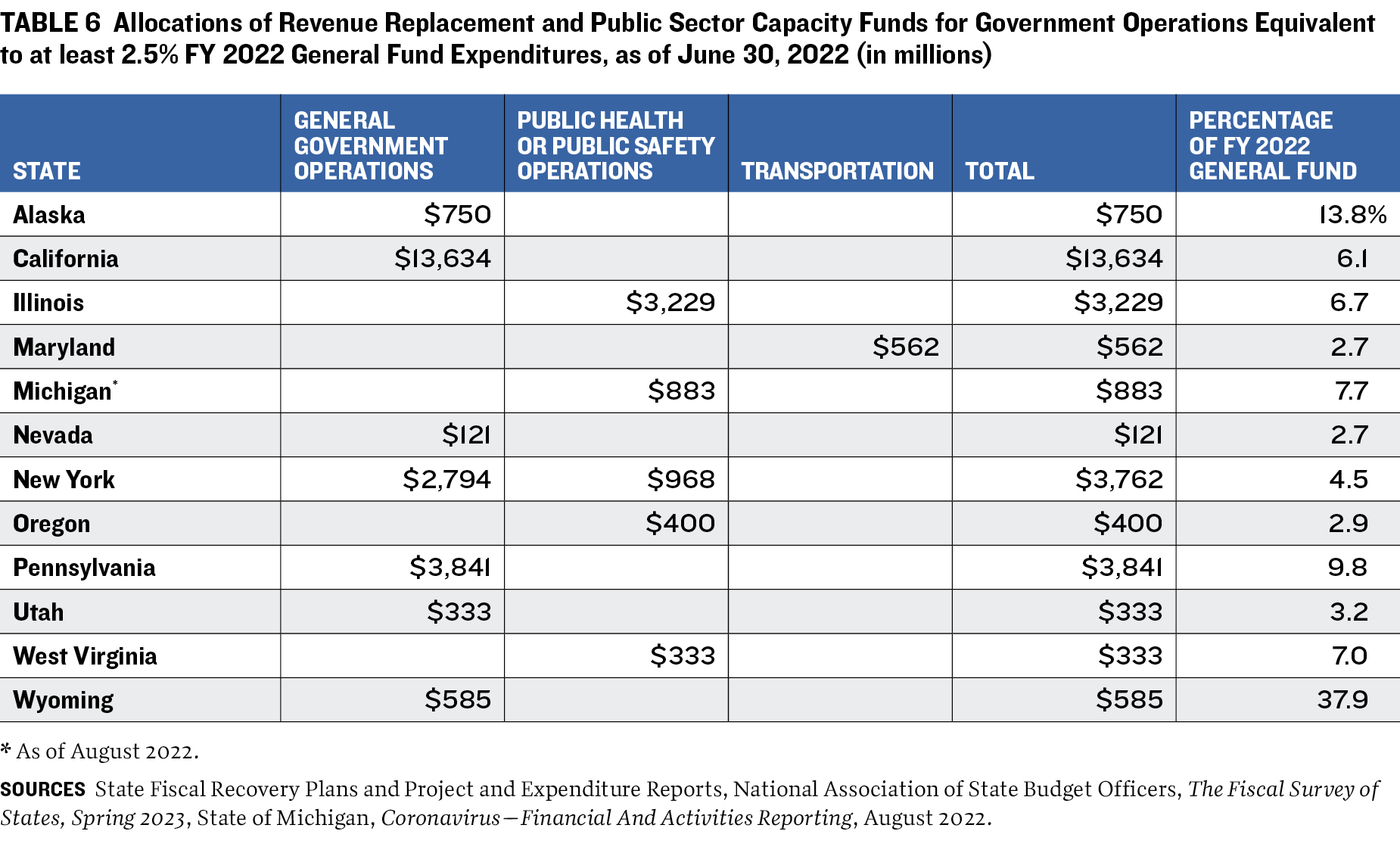

The use of SLFRF for operations increases the risks of a fiscal cliff when the federal funds are no longer available. States that accounted for much of the SLFRF designated for governmental operations are shown in table 6; each of these states allocated amounts for operations that were equivalent to 2.5 percent or more of their fiscal 2022 general fund expenditures. In three states (Alaska, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming), the amount allocated for government operations was 10 percent or more, and in three others (California, Illinois, and West Virginia) it was 5 percent or more.

Some states provided a description in their fiscal recovery plans of the types of general government operations financed with SLFRF. Alaska, for instance, put $750 million in SLFRF toward supporting services such as public advocacy, public defenders, corrections, troopers, the court system, the Alaska Pioneer Homes Payment Assistance Program, the Division of Juvenile Justice, and the Senior Benefits Payment Program.51 California deployed $13.6 billion to restore state employee pay; fund health and human services programs, higher education, and California courts; and avoid planned budget deferrals for local school districts and community colleges.52 Utah transferred $333 million into the general fund to cover “the costs of essential government services,” including corrections, public safety, courts, and social services.53

New York used $2.8 billion in SFLRF to finance government services and $968 million to pay salaries of state employees who work in public health or public safety. The government services component includes salary costs for services, including “tax and finance, transportation, parks and recreation, agriculture, child and family services, public safety, and other general government service operations.”54 It also comprises funds for Social Security payments on behalf of state employees and payments to local government related to support services and probation aides.

Fiscal recovery plans for Wyoming and Pennsylvania contained less information about how the SLFRF designated for general fund operations would be used. Pennsylvania’s report discussed major increases in the general fund in fiscal 2023, such as money for the Department of Education and the Department of Human Services (which oversees the state’s Medicaid program), but did not detail the distribution of a $3.8 billion transfer into the general fund.55 Wyoming did not provide a full breakdown of how the $585 million was being used but indicated that a portion financed the operations of the corrections and health departments that otherwise would have been paid for with general fund revenues.56

Nevada, meanwhile, allocated $121 million to fund returning its workforce to prepandemic levels.57 This included $93 million and $27 million for restoring positions in the state System of Higher Education and other government agencies, respectively. These positions were being held vacant, were subject to furloughs, or had been eliminated because of the fiscal impacts of the pandemic.

Some states designated the use of SLFRF for operating costs for public safety, corrections, or public health. In addition to New York, these included Illinois ($3.2 billion),58 Oregon ($400 million), and West Virginia ($333 million). The last allocated SLFRF to support costs such as personnel expenses in the Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation and in the State Police, as well as personnel expenses, equipment, contractual services, and other operational costs in the Department of Health and Human Resources.59 Michigan had not used SLFRF for revenue replacement as of June 30, 2022,60 but it released a report in August 2022 that showed $883 million (equivalent to 7.7 percent of its general fund spending in fiscal 2022) had been allocated to the Department of Corrections for revenue replacement.61

Maryland also used a substantial amount of SLFRF for government operations, deploying $562 million to provide budget relief for the state Department of Transportation, including transit operations and highway services.62

APPENDIX B: Tracking SLFRF Spending

TRANSPARENCY IS ESPECIALLY IMPORTANT given the unprecedented levels of federal funds flowing to state and local governments to address the pandemic and its economic impacts. The US Treasury requires state governments to submit annual state fiscal recovery plans that describe how SLFRF are being used, as well as related information. The plans vary in terms of details, as do other SLFRF reports posted on state websites.63 For example, among the eleven largest states, Florida is the only one that clearly identifies SLFRF as nonrecurring in its budget financial outlook statement and keeps those funds separate from the base budget.64 Texas, meanwhile, passed a separate appropriations bill to authorize the use of SLFRF,65 which makes it easier to identify programs or projects that are financed with these one-time funds.

For reports that states have filed with the Treasury, the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) maintains a web page that includes links to fiscal recovery plans,66 and a National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) web page tracks appropriations of SLFRF by state and category. The categories include arts and tourism, broadband, economic development, education, health, housing, human services, state operations, unemployment insurance, water, and other.67

Several of the largest states also have websites that track SLFRF. Georgia’s online tracker shows SLFRF obligations and expenses in total and by grant program.68 The site indicates that the data are gathered weekly from the Office of Budget and Planning’s Grant Care database. The New York State comptroller also has a website that tracks COVID-19 relief programs.69 For the SLFRF program, it shows the total amount of funds received, spent, and transferred to the general fund. In New Jersey, the Governor’s Disaster Recovery Office provides a tracking system that shows SLFRF allocated and dispensed by category and programs within each category.70

Michigan’s State Budget Office posts monthly reports showing SLFRF expenditures and encumbrances broken down by US Treasury expenditure categories and departments.71 The Illinois governor prepares a monthly report that includes information on revenues, expenditures, transfers, and grants awarded from federal COVID-19 relief funds that is submitted to the Legislative Budget Oversight Commission and posted on the website of the state budget office.72 And in Texas, the state comptroller provides an infographic showing ARPA program funding under the bill for Texas and the nation.73

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS REPORT WAS MADE POSSIBLE in part by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. We acknowledge the considerable support provided by the late Paul A. Volcker, the Volcker Alliance’s founding chairman, as well as the numerous academics, government officials, and public finance professionals who have guided the Alliance’s research on state budgets for the last seven years. We are also grateful for the constant support and guidance of the late Richard Ravitch, the former New York State lieutenant governor and founding Alliance board member, who died in June 2023. Finally, we thank the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) for their efforts in compiling Recovery Plan Performance Reports submitted by states to the US Treasury Department.

ENDNOTES

The US Treasury’s final rule defines an obligation as “an order placed for property and services and entering into contracts, subawards, and similar transactions that require payment.” National Archives, Code of Federal Regulations, title 31, § 35.3, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-31/subtitle-A/part-35.

States also received federal funds for nonentitlement municipalities that must be passed on to those communities without additional restrictions. Entitlement local governments, which primarily are larger governments, received funds directly from the federal government. American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. Law No. 117–2 (March 11, 2021), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text.

US Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund Split Payments to State Governments, Dec. 16, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/split-payments-to-states-pub….

National Archives, Code of Federal Regulations, title 31, part 35 (2022), § 35.3, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-31/subtitle-A/part-35.

Pay-as-you-go refers to the financing of capital projects through cash from taxes, fees, and other sources. It does not include debt-financing.

National Archives, Code of Federal Regulations, title 31, part 35, § 35.6, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-31/subtitle-A/part-35.

In January 2023, the US Supreme Court dismissed Missouri v. Yellen, in which the State of Missouri argued that the state fiscal recovery fund tax provision was unconstitutional. The court agreed with the federal Court of Appeals that Missouri did not have standing to bring this case. In the State of West Virginia v. U.S. Dept. of Treasury, which involved 13 states, the Eleventh Circuit Court ruled that the tax provision was unconstitutional under the spending clause. Susan Parnas Frederick, ”Supreme Court Declines to Hear ARPA Case, Will Take Up Religious Accommodation,” State Legislatures News, Jan. 23, 2023, https://www.ncsl.org/state-legislatures-news/details/supreme-court-decl….

National Archives, Code of Federal Regulations, title 31, part 35, § 35.6, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-31/subtitle-A/part-35.

Congressional Research Service, The Unemployment Trust Fund (UTF): State Insolvency and Federal Loans to States, Jan. 13, 2023, 4, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS22954.

Utah State Legislature, Utah Legislature’s Guiding Principles for ARPA Funds, May 19, 2021, https://house.utleg.gov/utah-legislatures-guiding-principles-for-arpa-f….

Legislative Fiscal Analyst, Budget of the State of Utah and Related Appropriations: Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023, May 2022, 1–9, https://le.utah.gov/interim/2022/pdf/00002327.pdf.

State of Kansas, State of Kansas Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2022, 4, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Kansas_2022RecoveryPlan_SLT-….

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. Law No. 117–2 (March 11, 2021).

State of Texas, State of Texas Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, July 31, 2022, 8, https://gov.texas.gov/uploads/files/organization/regulatory-compliance/….

The Illinois state fiscal recovery plan indicates that the state’s FY 2022 budget included $1 billion in SLFRF and Coronavirus Capital Project Fund money for water, sewer, and infrastructure projects. As of June 30, 2022, the SLFRF project inventory showed $200 million as having been allocated for those purposes. Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, State of Illinois Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, July 2022, 19–21, https://budget.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/budget/documents/arp….

Eight of the eleven largest states have fiscal years that begin July 1. New York’s fiscal year starts April 1, Texas’s starts September 1, and Michigan’s starts October 1.

Office of the New York State Comptroller, Identifying Fiscal Cliffs in New York City’s Financial Plan, May 30, 2023, https://www.osc.state.ny.us/reports/osdc/identifying-fiscal-cliffs-new-….

California Department of Finance, 2021 California Recovery Plan Performance Report, 4, https://dof.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/352/budget/covid-19/state-f….

State of California, California Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2022, 4, https://dof.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/352/budget/covid-19/state-f….

The three programs that were recategorized were the Statewide Child Savings Account program ($1.4 billion), Education and Training Grants for Displaced Workers ($472 million) and Revitalize California Tourism ($95 million). The state budget summary explains that this was done to maximize funding flexibility and streamline administrative procedures. Gov. Gavin Newsom, California State Budget 2022–23, 96–97, https://ebudget.ca.gov/2022-23/pdf/Enacted/BudgetSummary/FullBudgetSumm….

Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, State of Illinois Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, July 2022, 2, https://budget.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/budget/documents/arp….

Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, State of Illinois FY 2023 Economic Forecast and Revenue Estimate Update, Nov. 15, 2022, 20–22, https://cgfa.ilga.gov/Upload/11152022RevenueEstimateEconomicForecast.pdf .

Illinois made an additional $450 million payment toward the federal unemployment trust fund federal loan in October 2022 using unemployment tax revenues that were available because of a decline in unemployment claims. Mike Miletich, “Illinois Paying Off $450 Million of Unemployment Insurance Fund Debt,” 23 WIFR website, Sept. 27, 2022, https://www.wifr.com/2022/09/27/illinois-paying-off-450-million-unemplo…. In January 2023, Illinois repaid the remaining $1.36 billion federal unemployment trust fund loan using state funds. “Gov. Pritzker Announces Illinois Has Paid Off Remaining Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Debt,” press release, Jan. 25, 2023, https://www.illinois.gov/news/press-release.25960.html.

Illinois later revised the $3.2 billion figure to $1.5 billion. Illinois Project and Expenditure Report, January 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/January-2023-Quarterly-Repor….

State of Illinois, Budget Update and Rating Presentation, September 2022, 9, 25, https://capitalmarkets.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/capitalmarke….

According to the 2022 North Carolina fiscal recovery plan, the state legislature revised some of those appropriations in July 2022. The revisions were not identified in the plan for that year, however. State of North Carolina, State of North Carolina Recovery Plan Performance Report, July 31, 2022, 5, https://ncpro.nc.gov/july-2022-sfrf-recovery-plan-performance-report/op….

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, July 31, 2022, 2, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Pennsylvania_2022RecoveryPla….

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Recovery Plan, 4.

These costs initially were categorized under revenue replacement but were later moved to the public health category. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Recovery Plan, 12.

State of Florida, State of Florida Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, July 31, 2022, 10, https://www.floridadisaster.org/contentassets/021d63b30a604432a77d8905d….

Florida Department of Education, New Worlds Reading Initiative, https://www.fldoe.org/academics/standards/just-read-fl/nwri.stml.

State of New Jersey, New Jersey Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2022, 3, https://gdro.nj.gov/tpbackend/documents/New_Jersey_2022_Recovery_Plan_P….

State of New Jersey, New Jersey Appropriations Act FY 2023, June 30, 2022, 267–69, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/23bill/AppropriationsAct.p…;

State of Texas, State of Texas Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, July 31, 2022, 8–27, https://gov.texas.gov/uploads/files/organization/regulatory-compliance/….

State of Ohio, State of Ohio Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, July 31, 2022, 3. https://archives.obm.ohio.gov/Files/Budget_and_Planning/Ohio_Recovery_P….

State of Ohio, State Fiscal Recovery Funds, https://www.ohiopovertylawcenter.org/ohio-arpa-tracker#FRF.

State of Michigan, State of Michigan Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2022, 2, https://www.michigan.gov/budget/-/media/Project/Websites/budget/Fiscal/….

State of Michigan Recovery Plan, 2.

State of Michigan, August 2022 COVID-19 Expenditure Report, August 2022, https://www.michigan.gov/budget/-/media/Project/Websites/budget/Fiscal/….

Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget, State of Georgia Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2022, 4–8, https://opb.georgia.gov/document/document/state-georgia-recovery-plan-2….

James Salzer, “With $875 Million Available, Georgians Ask for $14.6 Billion in COVID-19 Relief,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Nov. 8, 2021, https://www.ajc.com/politics/with-875-million-available-georgians-ask-f….

Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget, State of Georgia Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2022, 6, https://opb.georgia.gov/document/document/state-georgia-recovery-plan-2….

State of New York, Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Enacted Budget Financial Plan, May 2021, 11, https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/en/fy22en-fp.pdf.

New York State Division of the Budget, SLFRF Recovery Plan Performance Report, July 2022, 20, https://openbudget.ny.gov/covid-funding/slfrf/nys-slfrf-2022-recovery-p….

The comptroller initially also identified an increase in the corporate franchise tax that was scheduled to end in 2023, but the state later extended the increase through Dec. 31, 2026. Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli, State Fiscal Year 2022–23: Enacted Budget Financial Plan Report, July 2022, 16, https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/budget/pdf/budget-enacted-fin… and Enacted Budget Report, State Fiscal Year 2023–24, May 2023, 2, https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/budget/pdf/enacted-budget-rep….

Gov. Kathy Hochul, “Statement from Governor Kathy Hochul on the MTA Receiving $769 Million in Additional COVID Relief Funding from the Federal Transit Administration,” March 7, 2022, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/statement-governor-kathy-hochul-mta-re….

Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Direct Placement of Bonds, March 24, 2022, https://new.mta.info/investor-info/direct-placement-of-bonds.