Preparing Tomorrow's Public Service - What the Next Generation Needs

Executive Summary

Government agencies at all levels face management challenges of immense scale and complexity. In the decades ahead, these challenges will continue to grow as the nation confronts a wave of retiring career government professionals. Building and maintaining a highly capable public service that stands ready and able to effectively carry out public policies at all levels of government has never been more critical. Toward that end, the Volcker Alliance has undertaken this study to explore the skills and competencies most needed to prepare the next generation of great public servants. We hope that it will prove a catalyst for action at all levels of government.

The mission of the Volcker Alliance is to advance effective management of government to achieve results that matter to citizens. A core element of effective government is a highly skilled public workforce with capacities that are matched to the challenges identified by policymakers and are important to the public. In collaboration with experts from higher education, government agencies, professional associations, and other civic organizations, the Volcker Alliance set out to develop a study seeking to strengthen the public service by shedding light on two critical questions:

1. What skills and competencies do rising government leaders believe are most important for effectiveness in their jobs today and in the future?

2. What educational and professional development programs can help them as they prepare for leadership in government?

A unique contribution of this report is the input, through focus groups and a survey, of nearly 1,000 rising leaders from all levels of government who reflected on the capabilities most critical to their work and how they prefer to learn. This information is paired with interviews of senior experts in government and educational institutions to explore current leaders’ perspectives on how we can best prepare for the future. We hope this study advances an important conversation about how we can continue to uphold America’s public service legacy.

Section I explains the background of the Alliance’s work in building a capable public service and the purpose of the study. It describes the increasingly complex conditions of the public sector, as well as the importance of retaining and developing top talent. It also provides a broad overview of the study and explains this report’s distinct contribution.

Section II presents actionable recommendations for government agencies, government professional associations, and higher education and training institutions. Stakeholders are encouraged to help rising leaders join networks of peers and find mentors, while paying better attention to burnout and development opportunities aimed specifically at promoting resilience. Agency and professional association leaders are encouraged to codevelop assessments of public service motivation and leadership aptitude, as well as career-stage learning rubrics that can be developed to help supervisors guide rising leaders on a successful career path. Educational institutions and training providers are also urged to incorporate more field-based components into curricula and partner with government and professional associations to develop scalable professional education offerings that align with the priority competency areas.

Section III provides the study’s key findings from the survey of rising government managers. It begins with an overview of the survey questions and objectives. It explores rising leaders’ positive disposition to government service and the emphasis that they place on interpersonal leadership strengths. In addition, this section details rising leaders’ learning and professional development preferences for both content and format.

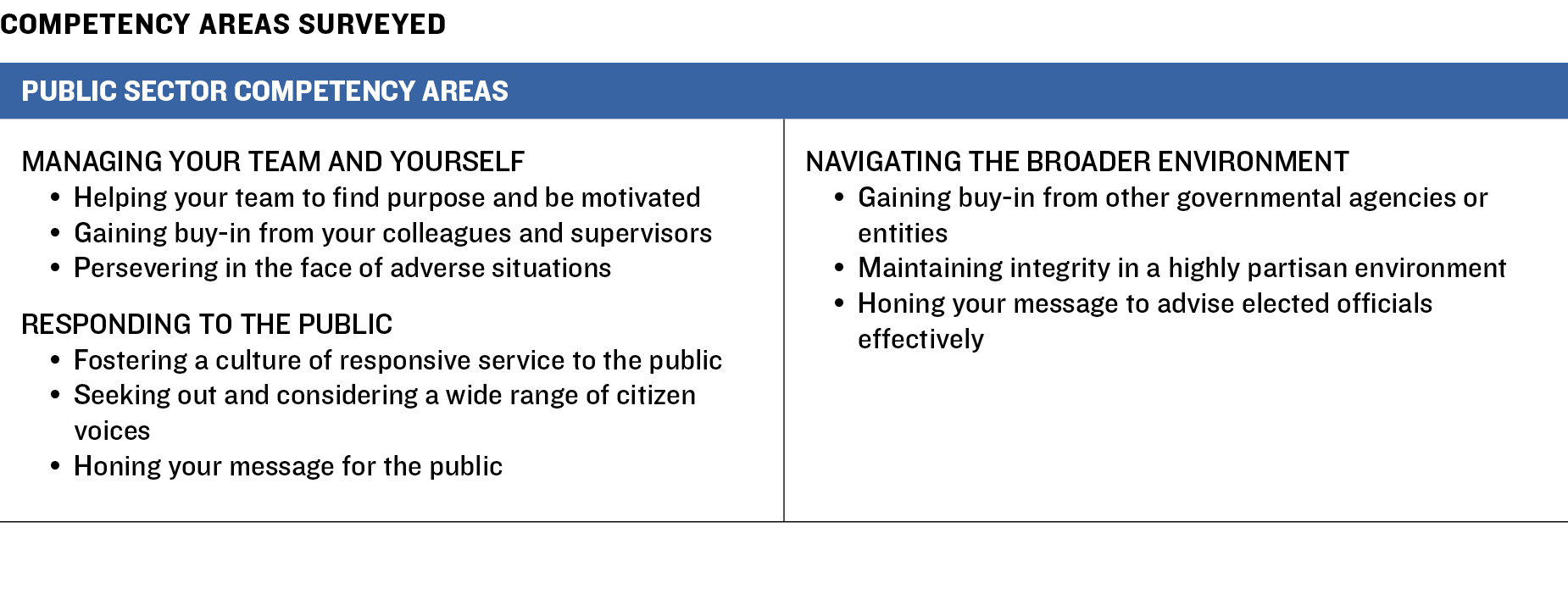

Section IV begins with an overview of the importance of interpersonal skills and then examines insights into competency areas in greater detail. The five competency areas that compose our taxonomy are:

1. Managing your team and yourself

2. Responding to the public

3. Navigating the broader environment

4. Data and technology skills

5. Business acumen

The discussion of each competency area includes the central takeaway and a description of the key learning drawn from the study’s focus groups, survey, and interviews.

Section V describes the characteristics of professional development approaches that study participants believe can best help rising leaders succeed in cultivating the competencies discussed in Section IV. The importance of networked learning and personal support via communities of peers and mentors is discussed. The section also considers approaches centered on collective problem-solving and the importance of career-stage development.

Section VI highlights some examples of professional development programs that incorporate one or more of the themes featured in the report. The list is drawn from the recommendations of advisers, experts, and survey respondents.

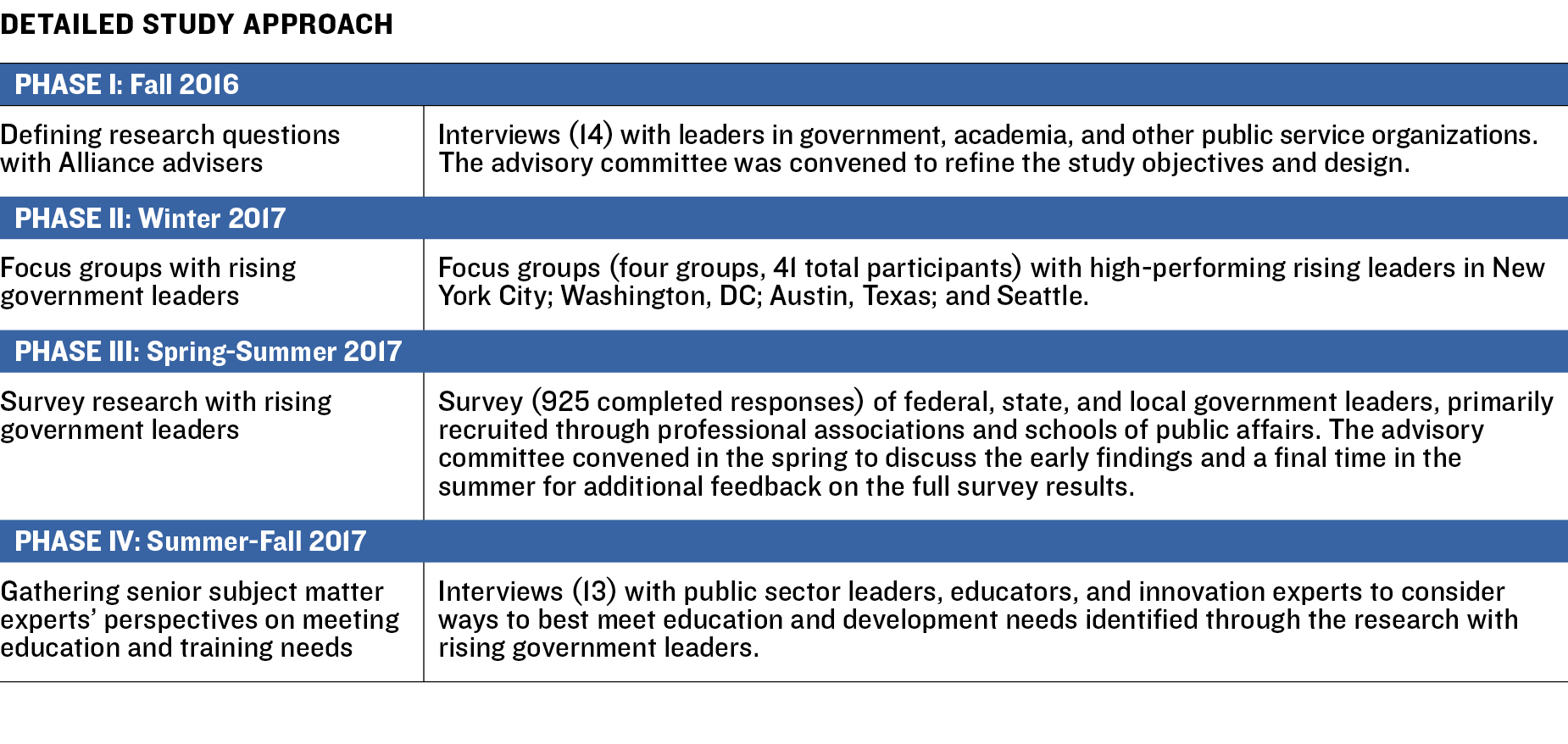

Section VII details the study approach and methodology. It defines the stakeholder groups referred to throughout the report and describes each of the four phases of work: Defining research questions with Alliance advisers; Focus groups with rising government leaders; Survey research with rising government leaders; and Gathering senior subject matter experts’ perspectives on meeting education and training needs. Section VII also provides the demographics for survey respondents.

We hope that this report provides valuable information and insights into how to best support the next generation of government leaders and amplifies the voices of those already calling for more attention to this issue. We invite and encourage government leaders, professional associations, education and training institutions, and other stakeholders to engage with our findings and to share their feedback with the Alliance team.

I. Introduction

Study Background and Purpose

The Volcker Alliance advances effective management of government to achieve results that matter to citizens. To support this mission, the Alliance partners with others to help build a highly capable public service that is ready and able to carry out public policies at all levels of government.

This study, Preparing Tomorrow’s Public Service, is a contribution to a far-ranging conversation about developing and retaining top talent in government service as the sector becomes increasingly complex and challenging. In the Alliance’s ongoing collaborations with universities, government agencies, professional associations, and civil society organizations, discussions continually turn to supporting the needs of rising government leaders who operate amid that complexity.

Because of its concern about the professional competencies of those who will assume leadership in government over the next decades, the Alliance selected and consulted a group of advisers from government, higher education, and government partnership organizations to reflect on a constellation of conditions shaping the public service landscape. Those conditions include:

• The government workforce is undergoing a rapid generational transition, with nearly one-third of federal career employees eligible for retirement by the end of the decade.1 Similar demographic concerns have made recruitment and retention the top priorities for state and local governments in recent years and have led the National Association of State Personnel Executives to identify “aggressively acquiring, retaining, motivating and rewarding talent” as one of its top five priorities.

• Dramatic increases in the scale and complexity of government’s responsibilities have not been matched by growth in its managerial resources, especially at the federal level. A recent survey of Senior Executive Service (SES) employees found that only 50 percent of SES leaders across federal agencies believe that their agency considers how future workforce trends impact their work, while the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports that technological advances have not kept pace with needs.

• The career civil service remains essential for effective governance, but current civil service models may not sufficiently motivate or measure the performance of career government professionals. The National Academy of Public Administration concluded that the current “human capital system actually hinders the ability of federal departments and agencies to recruit, develop, and retain top talent.”

Despite concerns about these challenges, the Volcker Alliance and its project advisers share another conviction: that federal, state, and local government has many highly effective leaders, and it is important to support their preparation and growth however possible. This commitment to support is both genuine—motivated by respect and admiration for the work of younger public servants—and highly practical. In his work on the conditions of American governance, Donald Kettl says that “many of the tasks of twenty-first century government, especially its critical coordination challenges, are at their core people-based challenges. Solving them will require skilled managers who can negotiate the constantly shifting forces of the administrative systems.”

As employers and educators of rising government leaders, Alliance advisers contribute significantly to the success and effectiveness of the vital government management workforce through training and development efforts. This study aims to enrich those efforts by seeking the perspective of rising leaders themselves on what it takes to do good work in government today. Because of the generational shift occurring in government, Alliance advisers agree that data and insights from the rising generation of leaders would be fresh and valuable contributions as the profession looks to its future.

This study hopes to spark productive conversation and inform the development of education and training support by asking two key questions:

1. What skills and competencies do rising government leaders believe are most important for effectiveness in their jobs today and in the future?

2. What educational and professional development programs can help them as they prepare for leadership in government?

The study does not seek to create an authoritative taxonomy of competencies needed for government management or to detail the specific content or applications of these skills. These are the important responsibilities of human capital specialists in government who design competency standards for their workforces and of the senior leaders who oversee the work of their agencies. Nor is the project designed to comprehensively survey the landscape of professional development offerings for public servants or to shape degree curricula at schools of government and public policy, a responsibility undertaken by the Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and Administration.

Rather, through this project the Alliance and its advisers aim to understand from the perspective of rising government leaders across federal, state, and local sectors those competencies that best enable them to effectively accomplish the work of government. Based on this understanding, the study seeks to provide insight into how agencies, professional associations, and educational institutions can support rising leaders in developing the competencies that will matter most for effective practice in the coming decade.

This Report’s Contribution

This report begins with a set of recommendations for stakeholders, including government agencies, professional associations, and higher education and training institutions. The recommendations draw on a set of key findings, which are highlighted in the next section. The findings delineate the core competencies that rising leaders identified as most important for effectiveness in government. A closer examination of each competency area follows, as well as insights and examples from government and education experts about professional development opportunities that help develop the individual skills.

The conclusions reflect the everyday constraints of making do with limited resources and relying on interpersonal skills to effect progress in government. Rising leaders believed that there should be investments in technology overhauls, new human capital management approaches, and comprehensive training and development programs to support them in their jobs. But rising leaders are realists. Pending these unlikely organizational transfusions, they lead by collaborating, being resourceful, and motivating their teams. Similarly, the professional development approaches that rising leaders and experts identified as most valuable draw on the energy and creativity of the rising leaders themselves. These approaches bring them together for networked learning, which provides opportunities for them to expand their professional circles, find fellowship, develop leadership strengths, and develop practical solutions for the problems they tackle daily in the course of making government function.

The report ends with a description of the study approach, which sets up a dialogue between the perspectives of senior experts in government and education and those of the broad population of rising government leaders working at the federal, state, and local levels. It details the qualitative and quantitative research approach conducted with these constituencies.

II. Recommendations

THE VOLCKER ALLIANCE ENCOURAGES all interested stakeholders—including government agencies, professional associations, and higher education and training institutions—to engage with the study findings in full, and it welcomes opportunities for dialogue about how all groups can contribute to the success and effectiveness of rising government leaders. The following ideas for action are grounded in this study’s findings and are drawn from the insights of its many focus group participants, survey respondents, and expert interviews.

For Government Agencies and Government Professional Associations

1. Assist rising leaders in building and joining networks, including those outside their agencies and functional silos. Networks provide support and leadership development opportunities for rising leaders and, just as importantly, build government capacity as participants codevelop approaches for tackling shared challenges.

2. Be attentive to burnout and promote professional development opportunities to cultivate resilience. Agencies must promote and support a culture of continuous learning and development and drive culture change in which employee training is viewed as an investment as opposed to a cost.

3. Capitalize on the sense of duty and public service ethos of talented young leaders by leveraging assessments to measure public service motivation and leadership aptitude. Rising government leaders are motivated by mission, and tapping into that motivation can support perseverance. Leadership assessments can help agencies ensure that those entering supervisory or managerial ranks are able to succeed.

4. Consider how to scale fellows programs to reach more rising leaders. The curricula and co-learning opportunities afforded by what have generally been small, selective programs and face-to-face requirements can be effectively extended through technology-enabled modes attractive to the larger rising leader population. Agencies must incorporate these programs into comprehensive talent management strategies to ensure that fellows are not merely returning to their old jobs with their same old duties.

5. Develop career-stage learning rubrics to guide rising leaders as they pursue professional development. Senior agency and association leaders can join to make recommendations for skills and strengths rising leaders should develop as they advance to progressive levels of responsibility.

6. Implement mentoring and coaching programs. These programs are a valued, effective, and low-cost means to support leaders at all levels in their professional development.

For Higher Education and Training Institutions

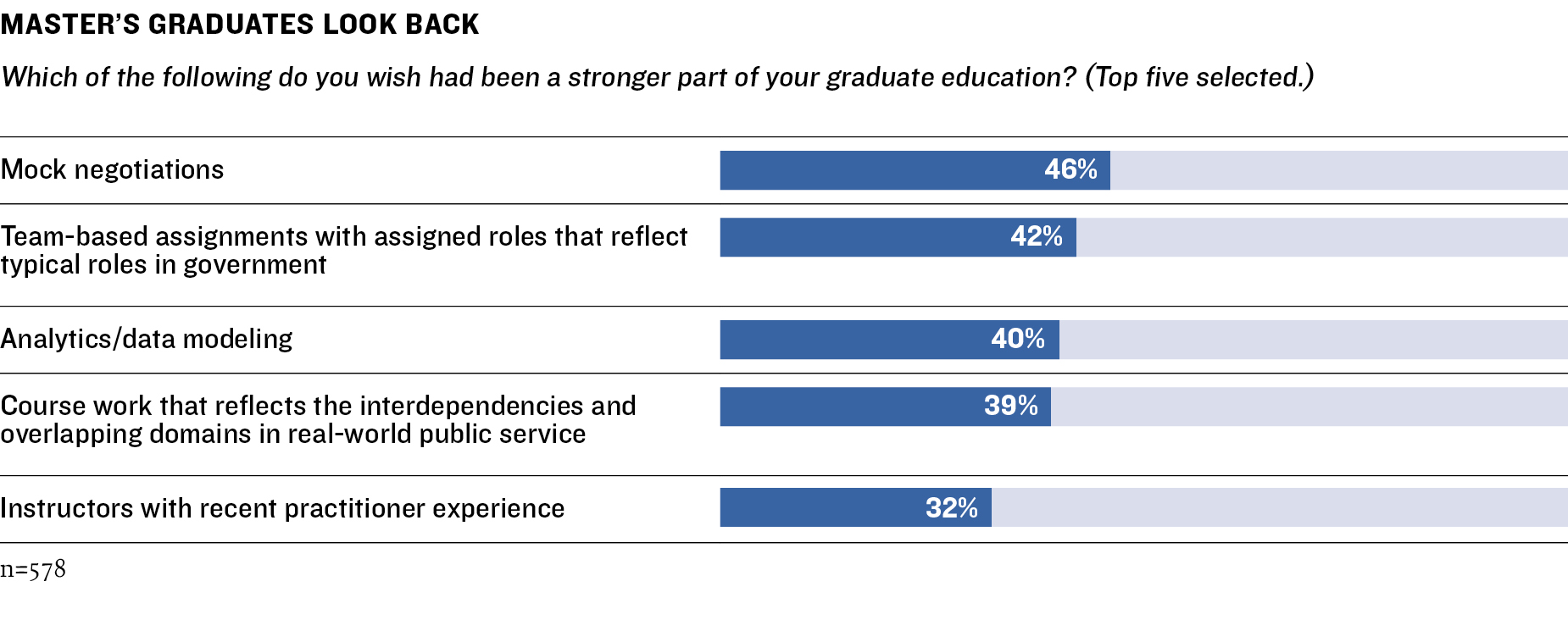

1. Incorporate more field-based content into graduate programs. Rising government leaders wish that field-based components such as mock negotiations, team-based assignments with assigned roles that reflect typical roles in government, and course work that reflects the interdependencies and overlapping domains in real-world public service had been stronger aspects of their graduate education.

2. Consider how to deliver learning and skills development aligned to career stages. Rising leaders develop needs for new leadership competencies and advanced skills as they progress in their careers, which in turn create opportunities for degree programs to offer post-degree courses and experiences (included in the degree program to amplify lifetime degree value or sold as low-cost add-on components).

3. Facilitate network development and mentoring through alumni communities. These communities are natural sources of the networks and mentoring relationships that rising leaders value.

4. Support campus communities of practice for students intending to work in government. Current students considering government can unite to reinforce their commitment to public service and orient to the world of practice through interacting with alumni and other practitioners.

5. Partner with government agencies and associations to develop scalable professional education offerings, especially certificate programs, aligned with the priority competency areas. Schools bring assets of mature-learning technology platforms and pedagogical expertise to partnerships with government. Rising leaders value certificate programs, which about one-third intend to obtain. Learnings from this study may be able to inform the design of these programs, which can be codeveloped and distributed through partnerships with government agencies and professional associations.

III. Key Findings

Survey Questions and Objectives

A survey conducted with rising government leaders across the country is a cornerstone of this study, providing detailed data representing the voices of those charged with addressing the practical challenges of public service. The Alliance team brings the concerns and expectations of expert advisers, as well as the rich insights of rising leaders gained in focus groups, to the design of the survey and its content areas.

The survey was designed to achieve several objectives:

• Evaluate the importance of professional competencies relative to their importance for effectiveness in government.

• Understand rising government leaders’ preferences about professional development.

• Record insights from rising government leaders about professional challenges, advice for peers, and learning interests.

To meet study goals, it was important that the survey was completed by a diverse set of respondents from a variety of regions, government levels, and educational experiences. The Alliance team invited the many professional associations and alumni relations offices in its network to distribute the survey electronically to their member lists.

In consultation with the advisory committee, the Alliance team developed the following list of competency areas to be tested in the survey. Each competency area included a set of specific skills that rising leaders deploy to achieve effectiveness in that area. This list reflects learning from the focus groups as well as adviser interviews.

Assessing the Competency Areas

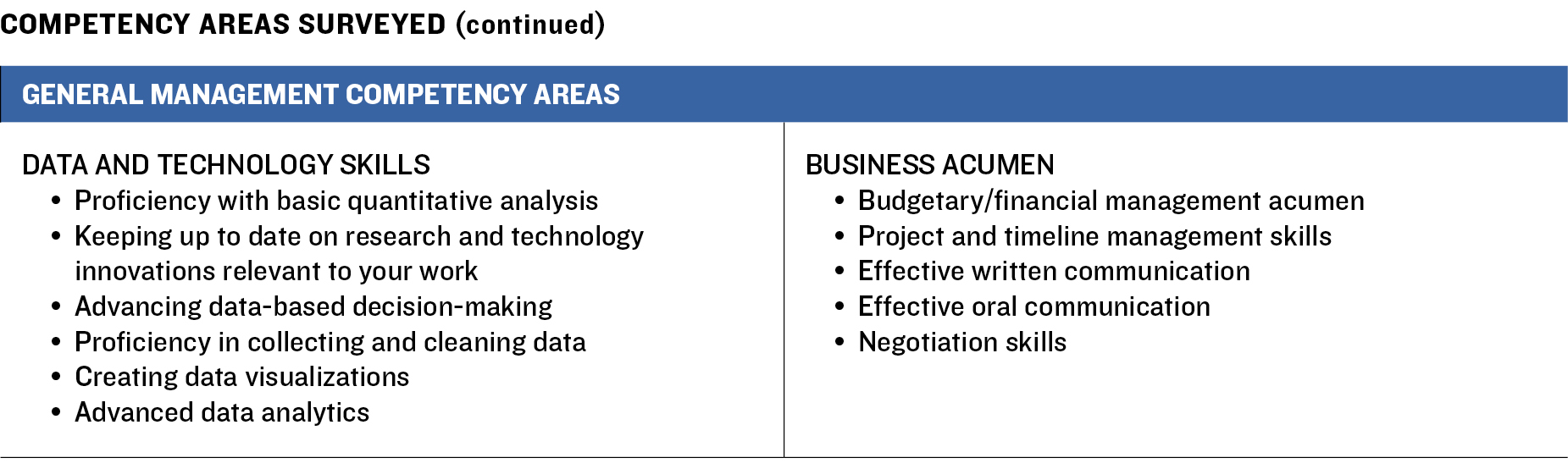

Survey respondents consider themselves to be successfully advancing in government service, and the majority indicate that they have support from peers and mentors.

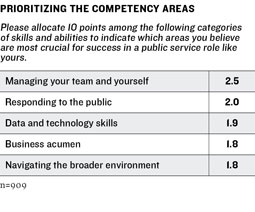

Rising government leaders reinforce the importance of leading and interacting with other people for effectiveness in their roles. When asked to allocate ten points among competency areas, survey respondents give strongest emphasis to “managing your team and yourself.”

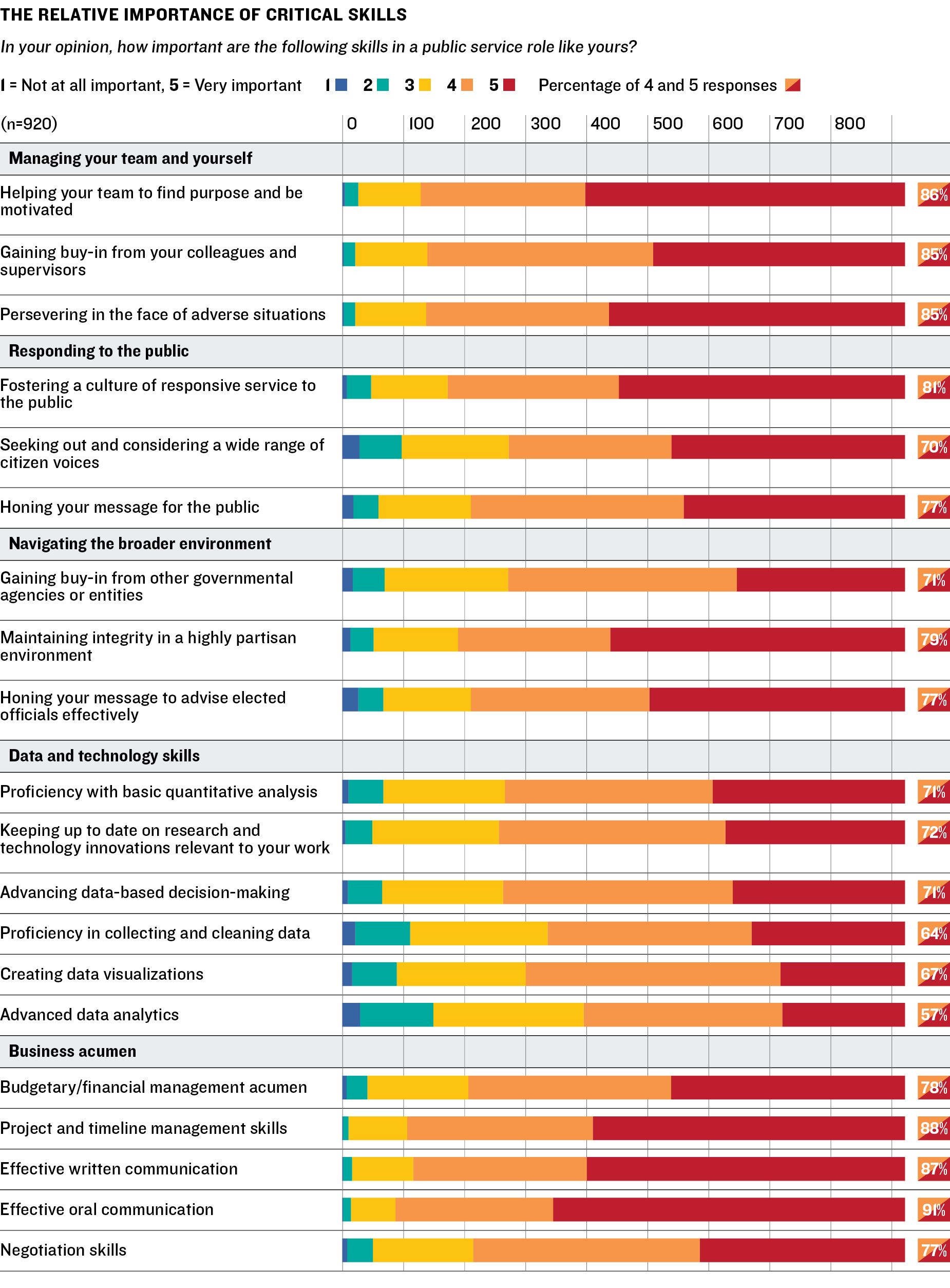

Detailed ratings of skills under the competency areas similarly bear out the importance of interpersonal leadership strengths. Along with the business acumen skills of effective oral and written communication and project management, the most valued skills involve influencing others and sustaining personal resilience in challenging circumstances.

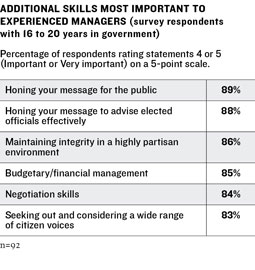

The most experienced rising leaders surveyed—those with sixteen to twenty years in government—are especially likely to prioritize skills needed to head departments and agencies and assume public-facing leadership. This is consistent with growing responsibilities and increasing public engagement as promising leaders advance in their career.

Learning and Professional Development Preferences

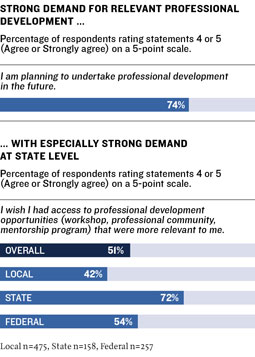

Rising government leaders value professional development. Their preferences suggest a market for continual, structured, and robust learning, as well as for more adhoc peer-to-peer networking and mentoring. While some respondents report that they intend to earn a certificate (35 percent) or degree (25 percent) to further their careers in public service, many more are interested in shorter-form development opportunities. Three-quarters of survey respondents report an intention to participate in professional development programs, and half wish that they had access to more relevant offerings. State-level rising leaders appear to be less satisfied with the availability of relevant offerings than peers in federal and local government.

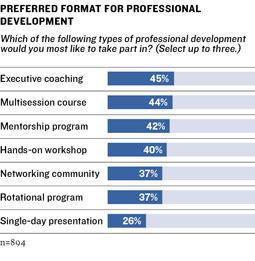

When considering their preferred format for professional development opportunities, respondents appreciate more intensive options such as executive coaching and multisession courses. Strong interest in mentorship programs and networking communities equally reveal the important value assigned to peer learning.

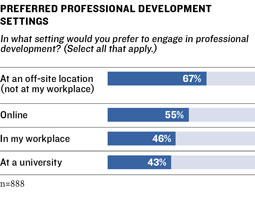

Rising leaders in the survey prefer to participate in professional development in a setting away from the workplace. More than half are open to online participation. Many focus group respondents express particular appreciation for professional development opportunities outside their department and away from their day-to-day responsibilities that allow them to focus on the opportunity at hand and build relationships with other leaders in different departments.

The following sections of this report further explore survey learning about competency areas and professional development needs in the context of insights provided by advisers and rising government leaders.

IV. The Competency Areas in Focus

Overview: The Importance of Interpersonal Skills

This study’s findings should inspire confidence about the future of the public service. They show that rising government leaders are committed (75 percent of survey respondents expect to stay in government for the long term) and motivated (71 percent believe they are making good progress in fulfilling their professional aspirations).

“Working in the government is complicated business. The founders’ system of checks and balances [is] both brilliant—and frustrating. You have to avoid the stereotype of the typical government worker and find ways to be creative and exceptional.”

RISING FEDERAL GOVERNMENT LEADER (SURVEY RESPONDENT)

Even more important, rising leaders understand the personal responsibility they bear for making government work. Findings reveal that rising leaders share convictions about what enables high performance and consistently emphasize the importance of personal capacity for leadership. Of course, personal strengths are not the only needed competencies. Foundational business and data-based decision-making skills are important, as they would be for any management workforce. So too is an understanding of how government works in practice—gained through formal education, personal experience, and advice and knowledge shared by peers and mentors. But above all, rising leaders assert that interpersonal effectiveness and personal resilience—commonly labeled “soft skills”—are essential for effectiveness in public service.

Given the urgent focus on technology and data in workforce development circles, it may appear counterintuitive or even naive that rising leaders consider soft skills to be of greatest importance. Indeed, many Alliance advisers expected rising leaders to clamor for data and business management skills to help address broad organizational and operational challenges. But while thought leaders interviewed for the study tend to focus on systemic issues, rising leaders on the ground are much more concerned with the everyday realities of making progress in environments shaped by scarce resources and challenged staff morale. Viewed from the rising leader’s perspective, interpersonal leadership supplies the vital energy that fuels government today.

Human capital leaders in government agree. “Because the nature of government has shifted, governing through influence and collaboration is the way we’re doing the work,” said Sydney Heimbrock, assistant director of the Center for Leadership Development at the US Office of Personnel Management. “In theory, if we are continuing to find government institutions critically underfunded, then it is equally important for someone in management to know how to analyze data as well as to lead people across sectors.”

“I need to know how things work technically on spreadsheets, but the skills I need are working on teams, being able to work with people, being able to work in different layers of bureaucracy, and being able to adjust myself and my expectations.”

RISING GOVERNMENT LEADER (NYC FOCUS GROUP)

The following sections examine in more detail the competency areas that rising leaders rely on to be effective in government.

A. Managing Your Team and Yourself

The Takeaway

Rising government leaders thrive by mobilizing their teams’ best energies, building partnerships when faced with complex challenges, and seeking to continually reinforce their own resilience and sense of purpose.

Key Learning

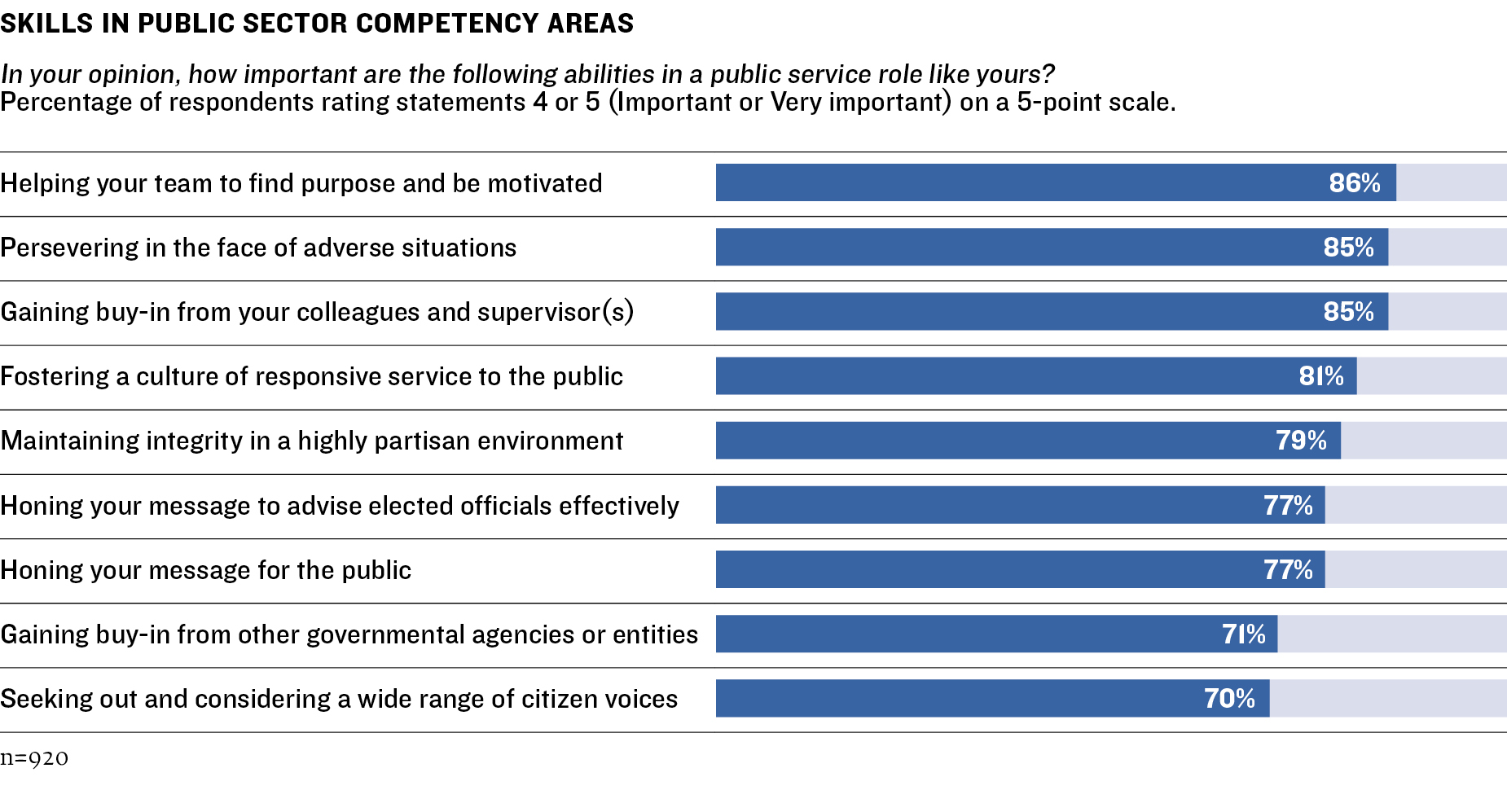

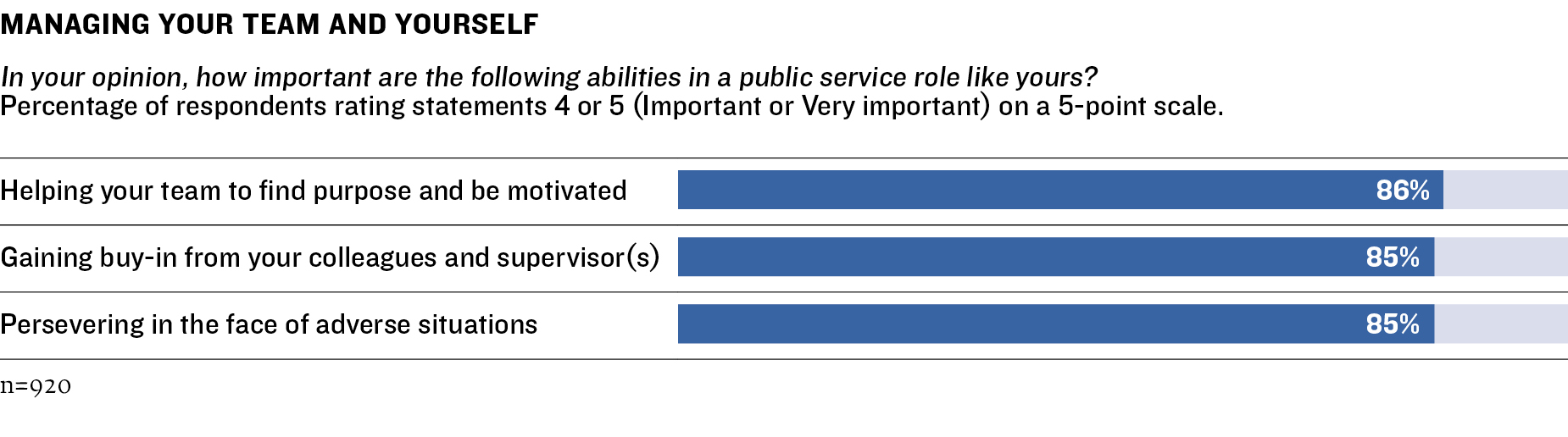

Skills in the “managing your team and yourself” competency area emerge at the top of the list as rising government leaders in the focus groups and survey emphasize succeeding through mobilizing their teams and forging partnerships across departments. “Helping your team find purpose and motivation” (86 percent top-rated) is among the five most important skills identified in the survey, followed closely by “gaining buy-in from colleagues and supervisors” (85 percent top-rated) and “persevering in the face of adverse situations” (85 percent top-rated). In their commentary, managers describe conditions where their staff members operate amid conflicting public expectations, policy-bound and resource-strapped agencies, and challenged morale. Often managers are supervising employees who have been working in government significantly longer than themselves.

Today’s rising leaders are often leading from the side, “managing up,” and seeking common ground with supervisees of all ages and experience levels who bring diverse backgrounds and values. For that reason, they emphasize the need to relate to people by understanding their experiences and perspectives. For rising leaders, supervising others is less about promoting a big vision or promising change than it is about evoking the best from staff over the long haul. Similarly, partnerships with peers and senior leaders across the organization rely on finding shared goals and developing joint projects that combine efforts and resources for greater impact.

“It’s servant leadership in government, about empowering people to succeed. To lead you have to listen and respect people’s values and ideas, and understand why folks are working in government to begin with.”

RISING GOVERNMENT LEADER (SEATTLE FOCUS GROUP)

“People who lack flexibility and emotional intelligence make it difficult for government to undergo change or any type of innovation.”

RISING GOVERNMENT LEADER (DC FOCUS GROUP)

Considering the fortitude that rising leaders say is required, it is perhaps not surprising that “persevering through adversity” (85 percent top-rated) is ranked one of the five most important skills for government service.

“Times in government can be tough and often your work will feel thankless. Sometimes you will have to reframe your thinking about being in government to find meaning in your work. Sometimes you will have to do this on a daily basis to keep yourself motivated. Sometimes it will be very difficult and roadblocks will seem insurmountable. But your work is important and the people we serve deserve—and need—your best efforts. And always remember that the grass isn’t necessarily greener in the private sector; there are challenges there too.”

RISING FEDERAL GOVERNMENT LEADER (SURVEY RESPONDENT)

Where does that personal resilience, the ability to persevere through adversity, come from? In initial conversations with senior academic and government leaders, some suggest that these qualities are intrinsic and that the sector must focus on recruiting individuals with the leadership qualities, public service motivation, and stamina to succeed in government. In the words of one SES member: “It’s difficult to teach resiliency but easier to identify who has it and who doesn’t.”

Today’s rising leaders are more comfortable with the idea that they can develop resilience like a muscle, particularly through fellowship with peers and guidance from mentors. Education innovators agreed that resilience can be developed. “Challenges deliver leadership life lessons,” said Julia Minson, assistant professor of public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “Back in the day, we looked for people who were good at managing through challenges and promoted them. Now we believe we can get everybody to be more effective.”

B. Responding to the Public

The Takeaway

Effective rising government leaders welcome the opportunity to engage with the diverse constituencies they serve and are attuned to new expectations for communications and transparency. This generation of leaders can be in a teaching role for their organizations in developing new approaches to responding to the public.

Key Learning

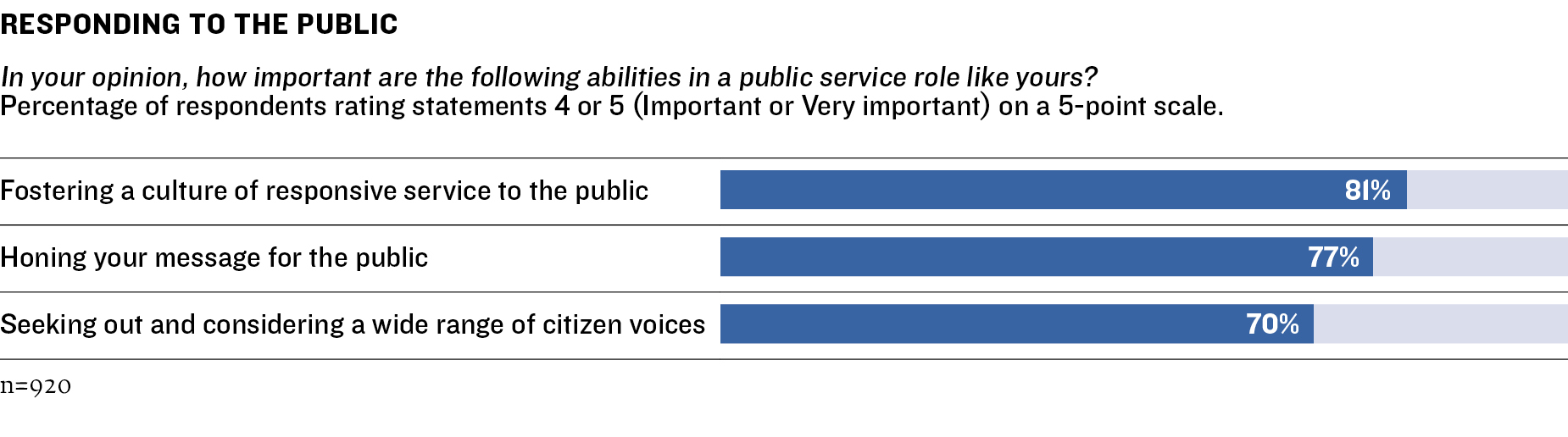

“Responding to the public” is the second-highest-rated competency area tested in the survey, and fostering a culture of responsive service is of particular significance.

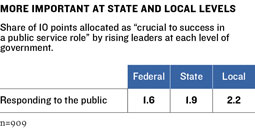

Survey findings reinforce the importance of responsiveness to the public, particularly for rising leaders at the state and local level, reflecting the immediacy of their contact with constituents. Our focus group respondents indicate that being responsive to the public can sometimes be challenging, but they report an understanding that it is a core responsibility of civil servants in a democratic society. Perhaps because they serve smaller constituencies, rising leaders in state and local government allocate more points to this competency area than do those in federal government.

Asked about how they learn or cultivate skills of responsiveness to the public, rising government leaders often refer to intrinsic public service motivations—their interest in learning about and helping citizens and communities. They underscore the importance and value of recruiting people into government who share this characteristic. People generally agree that these motivations, which are innate in some people, can also be cultivated with quality professional development and good leadership from skilled supervisors. The growing demographic diversity of many US communities requires that rising leaders be open-minded and empathetic to a range of citizen concerns. Responding to them draws on the same qualities that rising leaders leverage as they seek to motivate their teams and sustain personal resilience.

“You need to be interested and willing to learn about the people you’re serving. ... For me it’s all 2 million people in King County. And you need to be willing to build relationships in cultures that are not your own.”

RISING GOVERNMENT LEADER (SEATTLE FOCUS GROUP)

“Personally, I feel the greatest satisfaction when I can provide great customer service or educate a resident about what we are doing and why we are doing it. I’m doing everything I can to change the perception that government workers don’t care or that it’s just a redtape-filled bureaucratic agency. For me, it’s all about changing how people perceive government.”

RISING LOCAL GOVERNMENT LEADER (SURVEY RESPONDENT)

Of course, responsiveness goes beyond bringing a positive and engaging attitude to citizen concerns and service expectations. Here, Alliance advisers recognize that millennials may be better prepared than their elders to address emerging needs, particularly with respect to digital engagement and service. “Social media and digital technologies are increasing expectations of transparency and quicker outcomes—like citizens would expect from a private entity,” said Sharon Minnich, secretary of the Office of Administration for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Sydney Heimbrock at the US Office of Personnel Management is optimistic in considering the fit between community needs from government and this generation of leaders. “There is a huge opportunity, a seismic shift in managers’ and leaders’ awareness that business as usual doesn’t work,” she said. “People coming into the government workforce now are more attuned to the social dimension of everything we do. Digital natives find it natural to go and talk to citizens online. That opens up new approaches to democracy.”

C. Navigating the Broader Environment

The Takeaway

The government sector presents complex and unique management dynamics that are mastered through experience and with guidance from others. Rising government leaders prize opportunities to continuously learn more about how to effect change in the broader environment.

Key Learning

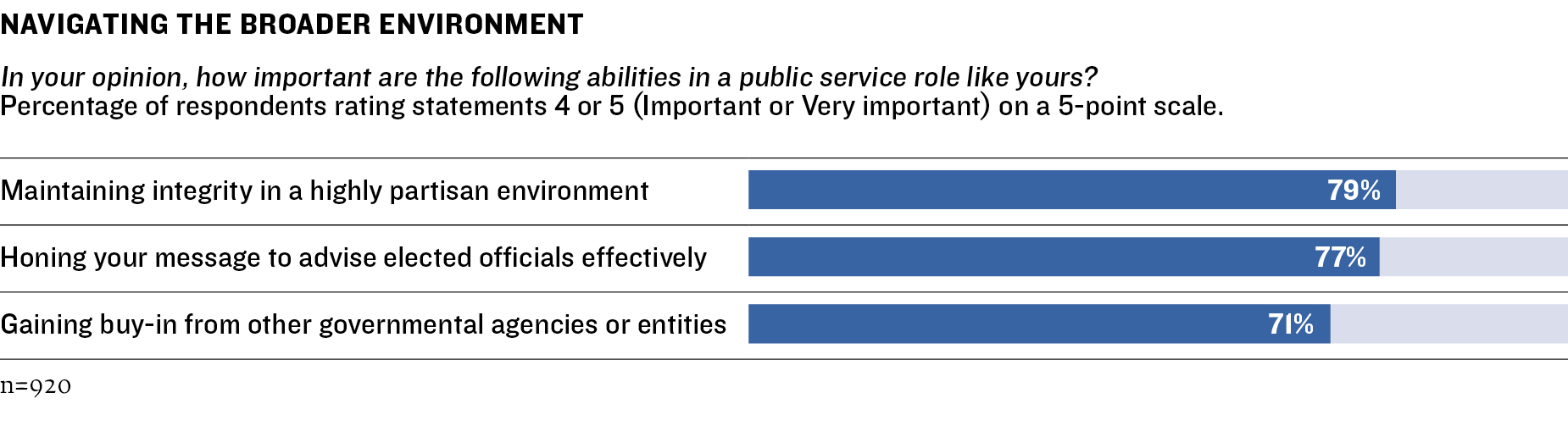

Skills related to navigating the broader environment are critical for all government leaders, and they gain importance as leaders advance and take on responsibility for managing and representing their departments inside and outside of government.

While this competency area is developed over the life of a career, participants in the study recognized that it is never too early to learn as much as possible about how government works in practice. “Instead of thinking of government as a crazy place that turns over all the time, we need to spend more time teaching people how to navigate the system,” said Terry Gerton, president of the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) and former deputy assistant secretary for policy at the US Labor Department’s Veterans’ Employment and Training Service. “We need to give people back their sense of agency and knowledge of how to do their jobs. It’s an empowering discussion about how the government works.”

Senior leaders in government are inclined to believe that navigating the broader environment is a competency area that can and should be more formally taught. Richard Spires, who has held senior roles at both the IRS and the Department of Homeland Security, asserted that “there is specialized training that government managers should go through about how government works and how things get done. The ‘rules of the road’ really are different in government.” In Spires’s view, the responsibility to provide this training belongs to the agencies, and rising leaders shouldn’t have to figure things out on their own. “This is about organizational maturity,” he said. “It’s not on the individual; it’s on the agency.”

Universities can also play a more effective role in providing learning from the field, according to study respondents. While three-quarters of rising government leaders with a master’s degree (from any discipline) consider their degree education to be valuable preparation for their government work, many wish that elements of field-derived learning had been stronger in their program.

The chart below shows a range of learning activities and content areas that government managers wish had been emphasized more in their degree programs. Several of these—including team-based assignments with roles that reflect ones typically held in government, mock negotiations, and coursework reflecting “real world public service”—reinforce needs expressed throughout the project for new graduates to be better attuned to the complex realities of government life when they hit the ground. Their favored professional development approaches reflect these preferences and are built on integrating instruction by experienced practitioners with peer-to-peer learning.

“Build your network of contacts. When in doubt, always reach out to others in the field to see how they have handled a similar situation. Don’t try to reinvent the wheel. Someone somewhere has come across a similar situation before and will have advice on how to (or how not to) handle it.”

RISING STATE GOVERNMENT LEADER (SURVEY RESPONDENT)

D. Data and Technology Skills

The Takeaway

Though government has a critical need for advanced data science and technology, many rising leaders are likely to be in roles where data and technology skills are less consequential than devising practical solutions to more immediate needs.

Key Learning

Technology transformation and its associated costs, risks, and opportunities are a common concern in government. Government experts are particularly concerned about the slow pace of adoption. The GAO has estimated that 75 percent of the federal government’s technology budget goes to maintaining legacy systems and only 25 percent to “development, modernization and enhancement.”

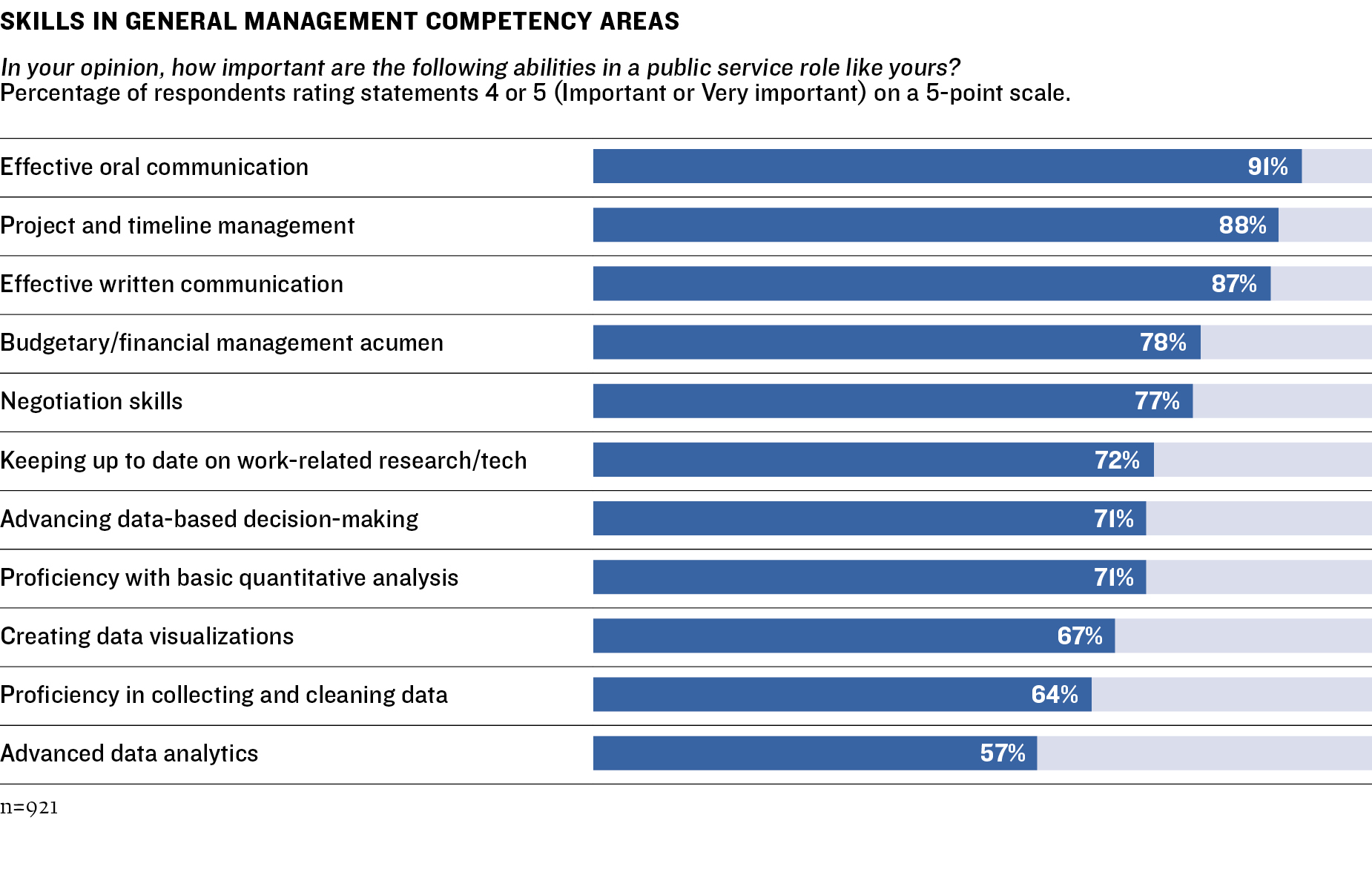

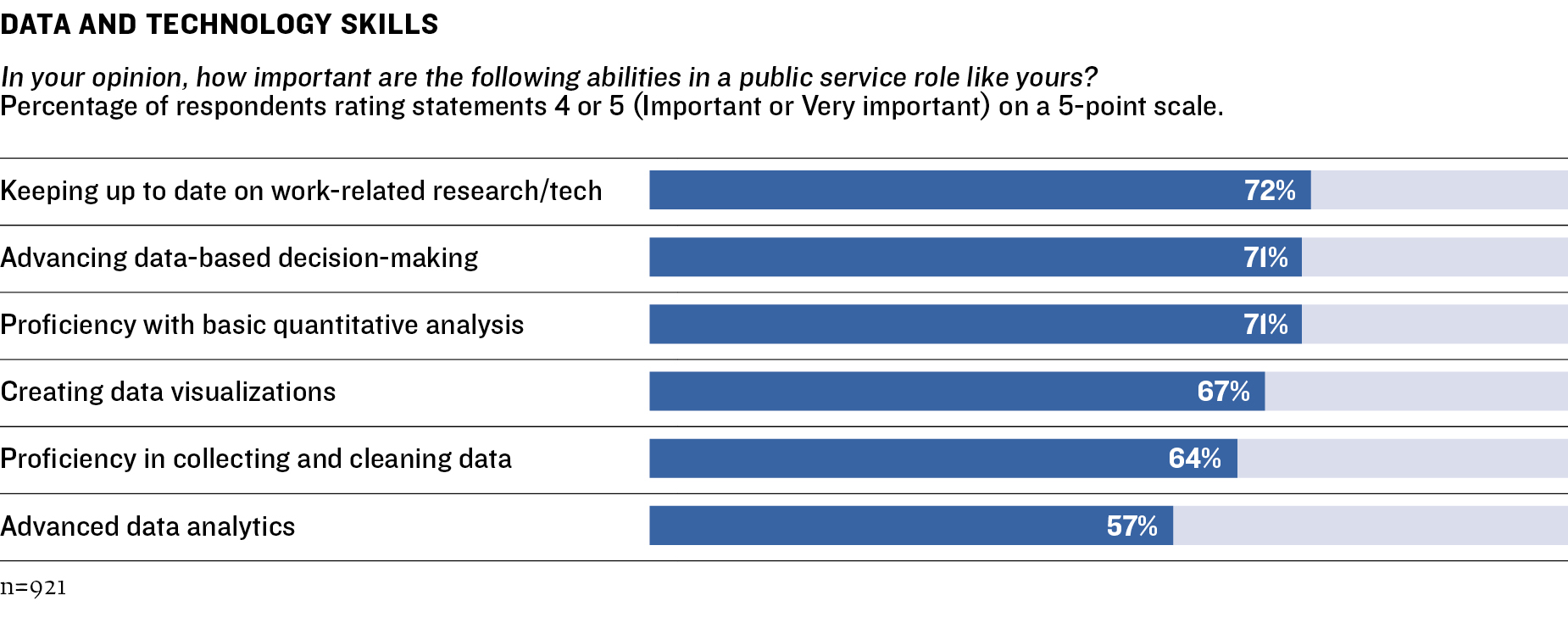

Considering the alarms sounded by experts about the government’s technology challenges, it is notable that none of the data and technology skill sets tested in the survey receive top importance ratings. As an example, “advanced data analytics”—the management science often described as transforming the private sector—is considered relatively important by only slightly more than half of respondents (57 percent).

Why don’t data and technology skills rate higher in importance in the survey? Ari Lightman, professor at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy, gathers government chief information officers for training to become “fast followers” in adopting tech sector approaches. But Lightman said changing political scenarios and insufficient resources usually intervene and limit managers’ ability to implement better technology processes.

The survey also shows greater importance given to “lighter touch” uses of data, such as making data-informed decisions, than to sophisticated technical skills such as cleaning data sets and conducting advanced analytics. This may suggest that while most leaders need solid familiarity with data’s interpretive aspects, a relatively smaller portion of this management cohort needs the most nuanced and sophisticated skills.

Others who have occupied senior government seats confirm the everyday constraints. “The fact is that IT systems in government were designed in the ’80s,” said Terry Gerton of NAPA. “Young people always want to go around the system, but managers need to have at least a rudimentary knowledge of how these legacy systems work because they generate the information you manage with.”

Of all the competency areas, the data and technology category may reveal the most pronounced gap between structural needs and practical realities. Over two-thirds of government managers with a master’s degree indicate that analytics and data modeling had been part of their graduate education, which suggests that a substantial portion of the government management workforce brings data skills. But these abilities may languish in environments where legacy infrastructure limits the potential to collect and analyze quality data. Similarly, legacy systems may limit opportunities to deploy technology skills to advance governance and serve citizens.

“Being data literate helped me make insights others weren’t. It stopped being useful quickly though, because so little policy work relies on generating new data or modeling. From my experience, most of public service was about managing up, staying crafty, and identifying opportunities to make a difference.”

RISING FEDERAL GOVERNMENT LEADER (SURVEY RESPONDENT)

E. Business Acumen

The Takeaway

Effective rising government leaders rely on communications and project management skills, and as they gain seniority they must add skills necessary for defending and advancing departmental aims. This finding seems consistent with professional expectations in the private and nonprofit sectors as well.

Key Learning

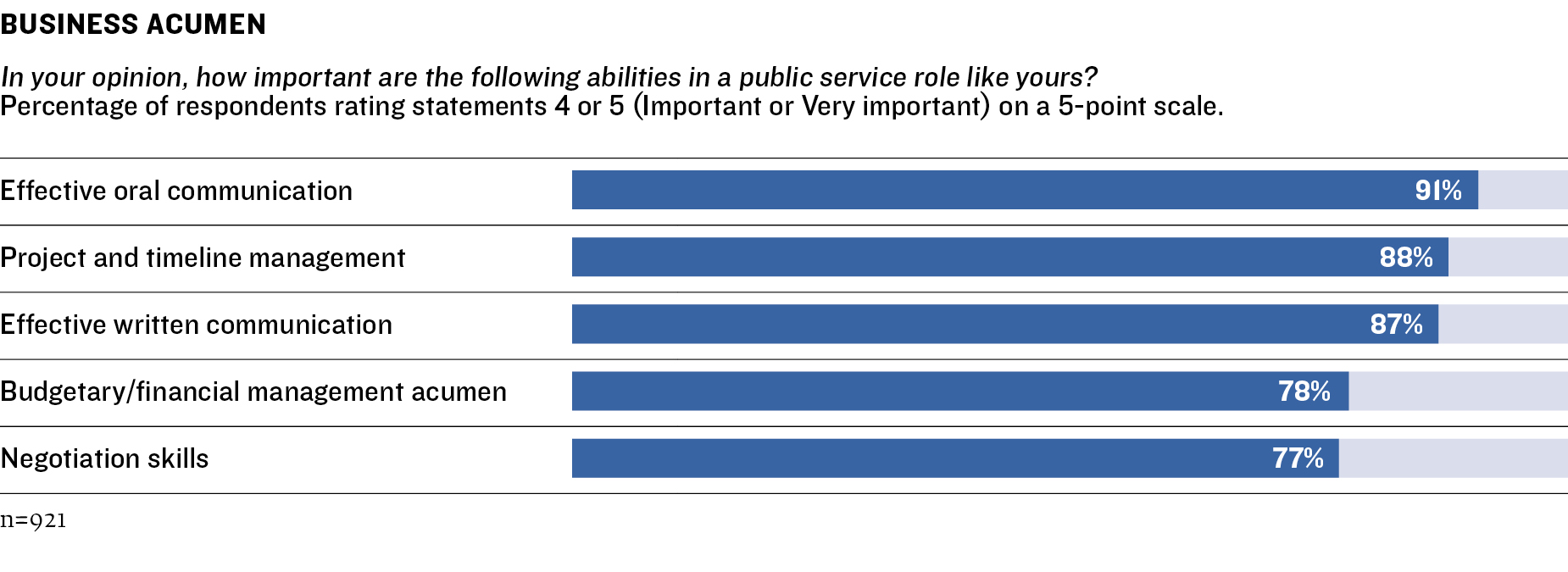

Rising leaders in the study reinforce that they need business acumen to be effective in government. In this competency area, they assign ratings of top importance to oral communication, project management, and written communications skills. In fact, effective oral communication and project management capacity are the most highly rated skills across all twenty skills in the five competency areas.

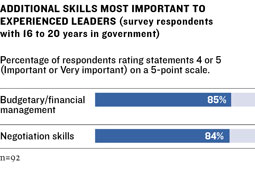

When it comes to management competencies, the survey reveals that rising government leaders must develop a more advanced tool kit as they progress in their careers. The most experienced leaders—those with sixteen to twenty years in government—rate skills and strengths needed to head departments and agencies and assume public-facing leadership as very important. These skills include financial management and negotiation, necessary for the work of defending and advancing department and agency-level aims.

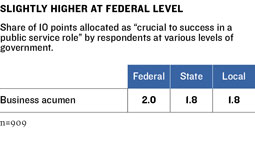

Alliance advisers emphasize the importance of management skills for those in government charged with successfully executing projects and leading teams in conditions of distributed authority. Federal government leaders put slightly more emphasis on business acumen. Some speculate that the scale of outsourcing and contracting at the federal level places a premium on this skill.

When it comes to management competencies, the survey reveals that rising government leaders must develop a more advanced tool kit as they progress in their careers. The most experienced leaders—those with sixteen to twenty years in government—rate skills and strengths needed to head departments and agencies and assume public-facing leadership as very important. These skills include financial management and negotiation, necessary for the work of defending and advancing department and agency-level aims.

Alliance advisers emphasize the importance of management skills for those in government charged with successfully executing projects and leading teams in conditions of distributed authority. Federal government leaders put slightly more emphasis on business acumen. Some speculate that the scale of outsourcing and contracting at the federal level places a premium on this skill.

V. Supporting Competencies through Professional Development

ARMED WITH FINDINGS about the competencies rising government leaders believe are most important for professional practice and their preferences for how they want to learn, the Alliance team conducted advisory committee sessions and interviews with experts in professional development and education innovation. In keeping with the study’s focus on supporting a broad base of government managers, conversations with experts centered on approaches that could enable wide participation and lower barriers to access for those with fewer resources.

Following are key characteristics of professional development approaches that study participants believe can help rising government leaders succeed in cultivating competencies for effectiveness.

Networked Learning

Leadership development built on professional networks is well-suited to government, where widening one’s circle of potential partners and learning from peers about “how to get things done” build the core competencies needed for effectiveness. Rising government leaders in the study continually returned to the value of learning with and from peers—in effect, crowdsourcing ideas and practices with others who share similar challenges.

Focus group participants described effective learning experiences gained at professional association meetings, alumni events, and conferences; in work training sessions; and through task forces and online communities. In fact, the focus groups for this study often concluded with participants networking informally and asking one another for contact information. The rising government leaders who completed the survey were identified from lists of many thousands provided by professional and alumni associations—essentially the record-keepers of networks.

Professional development approaches that create opportunities for wider participation through leveraging networks also make sense considering resource constraints in government. Rising government leaders certainly value significant employer investments in their careers. Many study participants laud fellows programs, in which agencies select cohorts of high-potential leaders for structured educational and leadership development curricula delivered over an extended period and usually in face-to-face sessions. Today, however, few agencies have sufficient resources to expand such programs, which tend to be expensive. Training and development funds are easy targets for budget cuts, and senior leaders in federal government often cite a lack of funding to explain why development needs are unmet.

Far from being a consolation prize, networked learning is viewed by many experts as an adaptive contemporary model reflecting the way management is practiced. For instance, professional development innovators at the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) describe conditions of scarce resources, distributed authority, and complex interdependencies as common in many sectors. They promote a new paradigm for professional development focused not on individual leaders but on networks of people who collectively share responsibility for unlocking leadership potential and effectiveness in their organizations.

Nick Petrie of CCL says that in many organizations and sectors, the question has changed from how to identify high-potential individuals to how “to spread leadership capacity throughout the organization and democratize leadership.”

“I think being able to network through a large group of people is extremely helpful. You are selling yourself but I don’t feel like its disingenuous. I have a mission and if you are able to speak to your mission, that’s going to help with building a broad network and make you better at your job.”

RISING GOVERNMENT LEADER (NYC FOCUS GROUP)

Personal Support

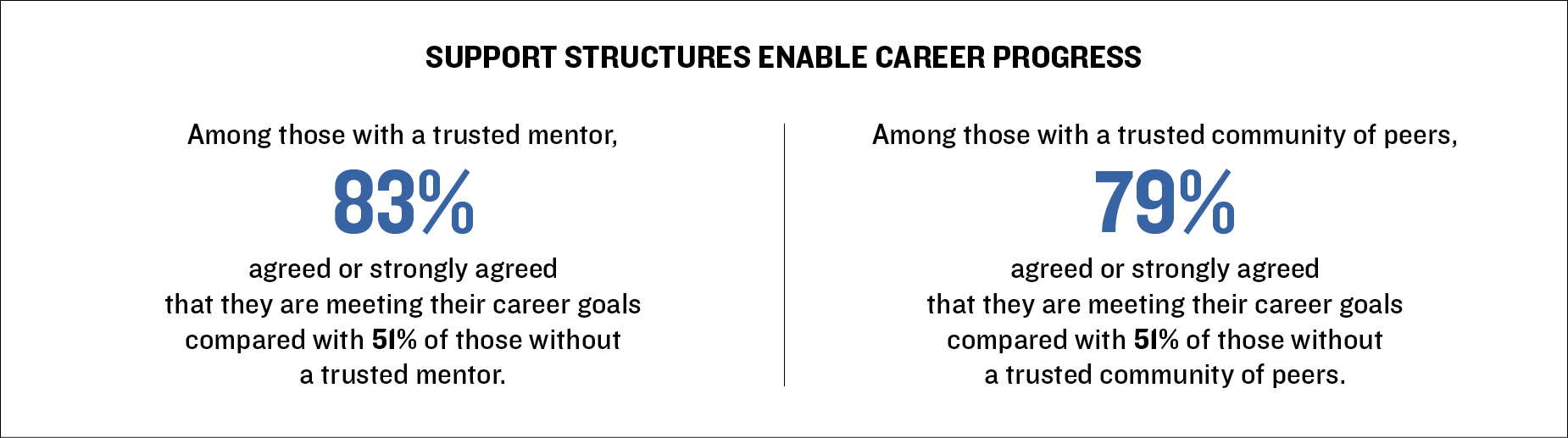

On a personal level, networks and mentoring relationships offer fellowship and support that help nurture resilience. Focus group participants frequently highlighted this benefit, and the study’s survey findings reinforce these effects. Rising government leaders with a mentor (63 percent of respondents) and those with a community of peers (74 percent of respondents) were significantly more likely to report that they were meeting their career goals. Causality must be attributed with caution, however, as it is also possible that those with mentors or a community of peers began with more confidence or received positive feedback from mentors or peers that has led them to believe they are meeting their goals when they might be falling short.

Effective mentoring programs are not necessarily formal or highly structured, but they do rely on systems that enable rising leaders to find and connect with senior leaders. Some government agencies are incorporating networking tools into their internal communications systems and giving greater emphasis to mentoring in their human capital management approaches. Schools of public affairs are encouraging and creating systems for alumni mentoring communities and leveraging digital platforms, such as LinkedIn, that enable alumni to connect. Professional associations have been at the forefront of establishing mentoring networks, some examples of which follow in Section VI.

“My favorite professional development experience was a one-on-one coaching opportunity with a past Director of a local government organization. Previously, I had not wished to attain a Director level position, but after speaking with this mentor and being able to ask questions about some of the hesitations I had, I worked through why I was holding myself back.”

RISING LOCAL GOVERNMENT LEADER (SURVEY RESPONDENT)

“I participated in two free mentoring programs. The relationships I developed through these programs kept me in government when I was nearly ready to leave for the private sector.”

RISING FEDERAL GOVERNMENT LEADER (SURVEY RESPONDENT)

“In the program I did we were away from the office; it’s a much more relaxed setting. It’s not fake and you don’t feel guarded. It’s more about learning from others’ experiences. You can share experiences and they don’t necessarily have to be savory. Over time, you constantly need to revisit and refresh your skills, seek some validation that your style and challenges are similar to others. … These experiences help people identify what does work.”

RISING GOVERNMENT LEADER (AUSTIN FOCUS GROUP)

Collective Problem-Solving

Many of the professional development programs recommended by advisers and experts have participants work together on shared problems, needs, or scenarios. Problem- or project-centered approaches produce practical value—good ideas for solutions to shared issues challenging government managers and agencies—while enabling participants to develop their own leadership skills.

David Altman of the Center for Creative Leadership stressed the multiple benefits of “learning while doing” leadership development: “When we ask leaders to reflect on the experiences they had that were influential in their development they tell us 10 percent of lessons learned comes from programs, 20 percent comes from social learning, and 70 percent comes from the school of hard knocks. You want to build approaches that allow people to put something into practice and reflect on it.”

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has launched the Next Generation Task Force, an innovative professional development program that unlocks the creative capital of its young government managers in just this way. One of the goals of the state’s Office of Administration is to reposition government service as a meaningful profession—to “rebrand government” as Sharon Minnich, who leads the office, put it. Inspired by the energy and ideas of the rising leaders she works with, Minnich and her team established a task force that has young managers crowdsourcing ideas for communicating the value and relevance of government service.

The task force was established to address the need of attracting young people to government service while providing fellowship and helping participants build leadership capabilities and a statewide network. By creating videos, holding public outreach events, providing recommendations to senior officers, and sharing best management practices, task force members are at the forefront of a campaign to demonstrate that the state government is open to new ideas, responsive to citizen concerns, and a great place for young people to make a difference.

Career-Stage Development

Study findings emphasize that rising leaders develop additional competency needs as they advance in their careers and assume responsibility for working across senior organizational levels and implementing the agenda of their departments. Recognizing the importance of career-stage development, government agencies and higher education institutions are looking at how to convey relevant skills when managers need them. Jon Nehlsen, associate dean at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy, said program leaders at his school are considering how to provide this “just-in-time” learning. “There are inflection points in a public service career, and the skills you need at each are different,” Nehlsen said. “Degree programs have tended to focus on the things you need to get the job and also on what you will need as you advance in five to ten years, but it may make more sense to get that learning when you need it.”

“At certain points in your career you’re going to need different things. The Air Force is good at this. They give you the experiential training and the leadership pieces and it’s throughout your career. They also send you out to public policy schools at appropriate stages.”

RISING GOVERNMENT LEADER (AUSTIN FOCUS GROUP)

VI. Professional Development Program Examples

The programs listed below incorporate one or more of the professional development themes and are included as exemplars of these themes in action. Drawn from the recommendations of advisers, experts, and survey respondents, the programs are aimed at rising managers (rather than senior executives), provide relatively broad access often aided by technology, and are open to interested participants (although applications may be required to determine eligibility). The list is not intended to be comprehensive but illustrative.

The Volcker Alliance welcomes the opportunity to collect additional examples of programs.

Alliance for Innovation, Innovation Academy

Offered in an online format, this program gathers cohorts of up to twelve people (from one organization or several entities) to gain leadership skills by tackling shared scenarios and needs. Participants are assigned a team mentor and attend nine interactive virtual sessions delivered monthly. https://transformgov.org/innovation-academy-virtual-program

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Leadership Programs

- Commonwealth Mentoring Program The program is designed to mentor employees via voluntary career guidance, networking and leadership development, and the transfer of institutional knowledge. Mentees attend five sessions over the program’s eight-month duration. Email [email protected] for more information.

- Emerging Leaders Program This ten-month program uses the Seven Pillars of Leadership model to develop character and leadership skills. Participants meet one full day each month. Each participant’s supervisor meets with that person regularly throughout the process and attends designated sessions with the participant. Email [email protected] for more information.

- Leadership Development Institute LDI provides professional development opportunities for commonwealth employees who demonstrate leadership potential and the ability to succeed in positions of greater responsibility within Pennsylvania government. Each LDI class participates in monthly sessions between March and October. http://www.hrm.oa.pa.gov/training-development/Development/Pages/default.aspx

- Next Generation Task Force This ongoing task force is directed by young government managers, who initiate projects and outreach to help attract millennials to government service and inspire trust in government among Pennsylvania citizens. http://www.hrm.oa.pa.gov/Pages/Contact-Us.aspx

GovLoop, NextGen Leadership Program

This is a government-wide virtual training program to develop and empower the next generation of government leaders. Program participants are matched with a mentor based on the executive core qualifications and the mentee’s specific action plan. Over the six-month program, participants engage in a series of online training sessions focused on leadership, development, and career advancement. https://go.govloop.com/Leadership-program-overview.html

Harvard Kennedy School of Government Leadership Programs

- Emerging Leaders This executive education program brings together Harvard faculty and an international cohort of rising professionals from the US and abroad for an empowering and energizing week of learning. Participants gain the skills and strategic framework necessary to capitalize on opportunities and overcome obstacles, returning home inspired to execute change. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/educational-programs/executive-education/emerging-leaders

- Leadership for the 21st Century This one-week program requires participants to be actively engaged on several levels—in the classroom, in small groups, and in individual reflection. Participants explore a wide range of leadership strategies and new ways of exercising leadership, whether in a position of authority or as one member of a group. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/educational-programs/executive-education/leadership-21st-century

International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Early Career Leadership Programs

- Emerging Leaders Development Program This is a two-year program intended to build knowledge, skills, and abilities in the basic management and technical areas that managers need to be successful. A coach is provided for each enrollee, and activities include monthly teleseminars with credentialed senior managers or public administration professors. https://icma.org/emerging-leaders-development-program

- Local Government 101 Online Certificate Program This program focuses on leadership, management, service delivery, budgeting, and human resources. Taught by experienced managers and experts, it imparts real-life experiences, best practices, and reliable advice in the areas most important to a manager’s day-to-day role. https://icma.org/local-government-101-online-certificate-program

- ICMA Coaching Program Webinars Live coaching webinars with experts include interactive polling, Q&A sessions, and open discussion about matters affecting local governments. Topics include entrepreneurial solutions, creating a culture of cultivating talent, taking smart risks, and recovering from setbacks. https://icma.org/icma-coaching-program-webinars

Office of Personnel Management (OPM), Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) Certificate Program

Provided through OPM’s Center for Leadership Development, this program offers five career-stage certificates, each completed in three to five face-to-face courses. They are designed to help federal leaders assess their leadership effectiveness, gain core knowledge, and develop critical skills for success. https://cldcentral.usalearning.net/mod/page/view.php?id=249

Rebecca Ryan, Futurist Camp

Leadership development experts guide participants through an intensive camp experience and six months of virtual collaboration. Participants apply learned futurist techniques and scenario-planning to a project in their own work environment. https://www.picatic.com/futuristcamp2018

Young Government Leaders (YGL) and Senior Executives Association (SEA), Mentorship Program

This effort pairs YGL members with SEA members, providing a confidential advisory relationship and broader exposure outside the young manager’s immediate organizational context. http://younggov.org/get-involved/mentoring/

Young Government Leaders and GovLoop, Next Generation of Government Training Summit

This two-day annual Summit in Washington, DC, brings together both emerging leaders and seasoned managers in federal, state, and local government to inspire innovation and provide training and leadership opportunities. Formats include breakout sessions, keynote speeches, and networking receptions. https://www.nextgengovt.com/summit-overview

VII. Study Approach

Key Stakeholders

The Volcker Alliance partnered with Huron Consulting Group and an advisory committee made up of senior leaders from government, academia, and public service associations for this study.

Key stakeholder groups referred to throughout the report:

Alliance team The staff of the Volcker Alliance and Huron Consulting Group who designed and managed the study.

Advisory committee The advisers from government, educational institutions, and government partnership organizations who provided guidance to the Alliance team over the course of its work. The committee met in three sessions to help define questions for inquiry and interpret study learning. Committee members also recommended individuals for participation as interviewees and focus group members. The advisory committee was not convened as an official approval body and not asked to endorse study findings or recommendations.

Rising government leaders Individuals employed in government at the federal, state, and local levels responsible for managing people, projects, and budgets. This study focused on “rising” leaders who had been working in government for less than fifteen years. The majority of rising leaders had been promoted one or more times in the past five years.

Senior subject matter experts Senior representatives from educational organizations, government agencies, and associations who shared expert perspectives on the roles and needs of government leadership, as well as on education and training to meet those needs. These individuals shared opinions and insights gained from the field and did not participate as official representatives of their organizations.

A complete list of advisory committee members and other experts interviewed for the study appears in Appendix A, along with a list of the Volcker Alliance staff who led this initiative and the Huron staff who supported this work. We are indebted to the associations and organizations, also listed, that distributed the survey to their members.

Detailed Study Approach

The study was conducted through four phases of work.

Phase I: Defining Research Questions with Alliance Advisers

In Phase I, the Alliance team conducted interviews with senior leaders in government and education, a subset of whom joined the study’s advisory committee, to define the most valuable objectives for the study and to guide project design. These first-phase discussions were wide ranging, reflecting advisers’ diverse concerns with systemic issues facing government and associated challenges in attracting, recruiting, and retaining top talent for the public sector.

Because the starting field of inquiry was broad and included the aim of being relevant at the federal, state, and local levels, the Alliance team worked with advisers to refine study parameters to provide a distinctive and discrete contribution. Advisers agreed that a focus on hearing directly from the rising generation of public servants who are poised to take on senior leadership in the coming decades, followed by consultation with senior leaders to interpret and validate needs, would provide added value to the current knowledge base.

As the Volcker Alliance’s mission is to promote effective government and to provide more actionable findings and recommendations, the study population was further narrowed to those rising leaders who work in government in a strictly defined manner—characterized by one adviser as those with “an eagle on their paycheck.” This choice was not intended to discount the important contributions of professionals who participate in public service through other means. Advisers from universities, for instance, noted that schools of public affairs prepare graduates for a wide range of public service environments and that at many schools a declining percentage of graduates join government service. But all advisers agreed that this cohort of rising leaders is especially critical to ensuring effective government.

Study advisers contributed guidance to the Volcker team as it prepared to conduct focus groups with rising leaders. They recommended several competency areas for exploration, including leadership and team building, data and business management, global and financial literacy, policy acumen, and negotiation.

Phase II: Focus Groups with Rising Government Leaders

In Phase II the Alliance team conducted focus groups with rising government leaders in New York City; Washington, DC; Austin, Texas; and Seattle. Each group comprised individuals in management roles with five to fifteen years’ experience in federal, state, or local government service. Participants were recommended by colleagues and Alliance advisers as “rising stars” who were advancing in government service and likely to hold senior leadership positions in the future. The focus group discussions were conducted over dinner in environments where participants could speak freely and confidentially about their careers in government service.

In the focus groups, participants were asked to reflect on the characteristics and practices that enabled them to be successful in government service, in terms of managing projects and teams and of accomplishing their department’s goals. As discussed in the prior sections, participants in all four cities strongly prioritized the role of interpersonal strengths and “earned experience” in being effective at work, emphasizing these along with communications skills over other functional skill sets, including data and financial management. Reflecting on professional development and education options they had already or wanted to access, focus group participants most valued opportunities to engage with peers and codevelop solutions to shared needs in the practice of government.

Phase III: Evaluating Competencies Through Survey Research with Rising Government Leaders

To learn more about the competencies and educational offerings valuable for government service, the project included a national survey of early-to-midcareer federal, state, and local government managers. Huron Consulting Group’s market research practice administered the survey. Respondents were recruited via distribution lists shared by the following professional associations and schools of public affairs.

Respondents first answered a short series of screening questions to confirm survey eligibility. Respondents were required to have at least two and no more than twenty years’ experience in government and to currently have a job in federal, state, or local government that included managerial responsibilities, such as the management of people, budgets, or time-bound projects. Respondents who had left their government positions within the last two years but met all the criteria were also permitted to complete the survey.

The survey had two primary content areas. First, respondents were asked to evaluate the relative importance of a list of broad competency areas and related skill sets that had been developed through the focus groups and advisory meetings. Second, they were asked about their preferences for professional development and other education activities to support their effectiveness at work.

The demographics of our survey respondents reasonably resemble that of the federal workforce, which is largely managerial. It would be difficult to separate managerial and nonmanagerial functions and aggregate data across states and localities; therefore, federal data serves as a proxy, although our data also includes respondents at the state and local level. We did not reweight the data for analysis.

Phase IV: Gathering Senior Subject Matter Experts’ Perspectives on Meeting Education and Training Needs

Finally, the Alliance team conducted interviews with educators, government leaders, and innovation experts to consider ways to best meet education and development needs identified through the research with rising government leaders. These experts helped interpret findings from the survey research and focus groups, and shared examples of professional development approaches and programs they had successfully implemented in their organizations. There was significant synergy among interviewed experts regarding effective development practices; in particular, experts emphasized the value of networked and peer-to-peer learning, as well as career-stage development models. These approaches and recommendations are described in previous sections of the report.

This report was made possible by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The Volcker Alliance is grateful for the participation of the following advisers and experts, as well as the rising leaders who joined our focus groups and responded to our survey.

Download the full report for a full list of study participants and acknowledgments, as well as the survey used in this study and endnotes.