Meeting the Trillion-Dollar Challenge: Tool Kit

Framework for Assessing and Reporting State Deferred Infrastructure Maintenance Needs

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND The US has accumulated at least $1 trillion in deferred maintenance at the federal and state level.1Budget constraints and competing priorities often lead government agencies to postpone or delay planned maintenance to make funding available for other pressing needs. The failure to keep up with maintenance results in higher expenditures in the future, however, and in some cases compromises the safety and health of people using these facilities.

Unlike other large obligations, such as debt and public worker pensions and other postretirement benefits, deferred maintenance is not included among liabilities on government balance sheets. While some states report deferred maintenance needs in their capital budgeting documents, there is no universally adopted system for assessing, valuing, and funding this gap.

AUDIENCE FOR THIS TOOLKIT It is designed primarily for state budget officers, legislative and executive staff, and state agency heads. It could also be helpful to other stakeholders and interested members of the public.

HOW THIS TOOLKIT WAS CREATED Its development was based on the experiences of nine states that are currently working to address their deferred maintenance needs. They were chosen because they have taken concrete steps to track, measure, and manage those needs. The nine states are Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Montana, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. (Tennessee is included as it has an inventory that considers state and local infrastructure needs, but it does not currently report deferred maintenance needs).

These states’ diverse approaches provide valuable examples of practices that might be useful for other states, whether they are just beginning to navigate and assess their long-standing maintenance backlogs or are looking to refine and strengthen existing strategies.

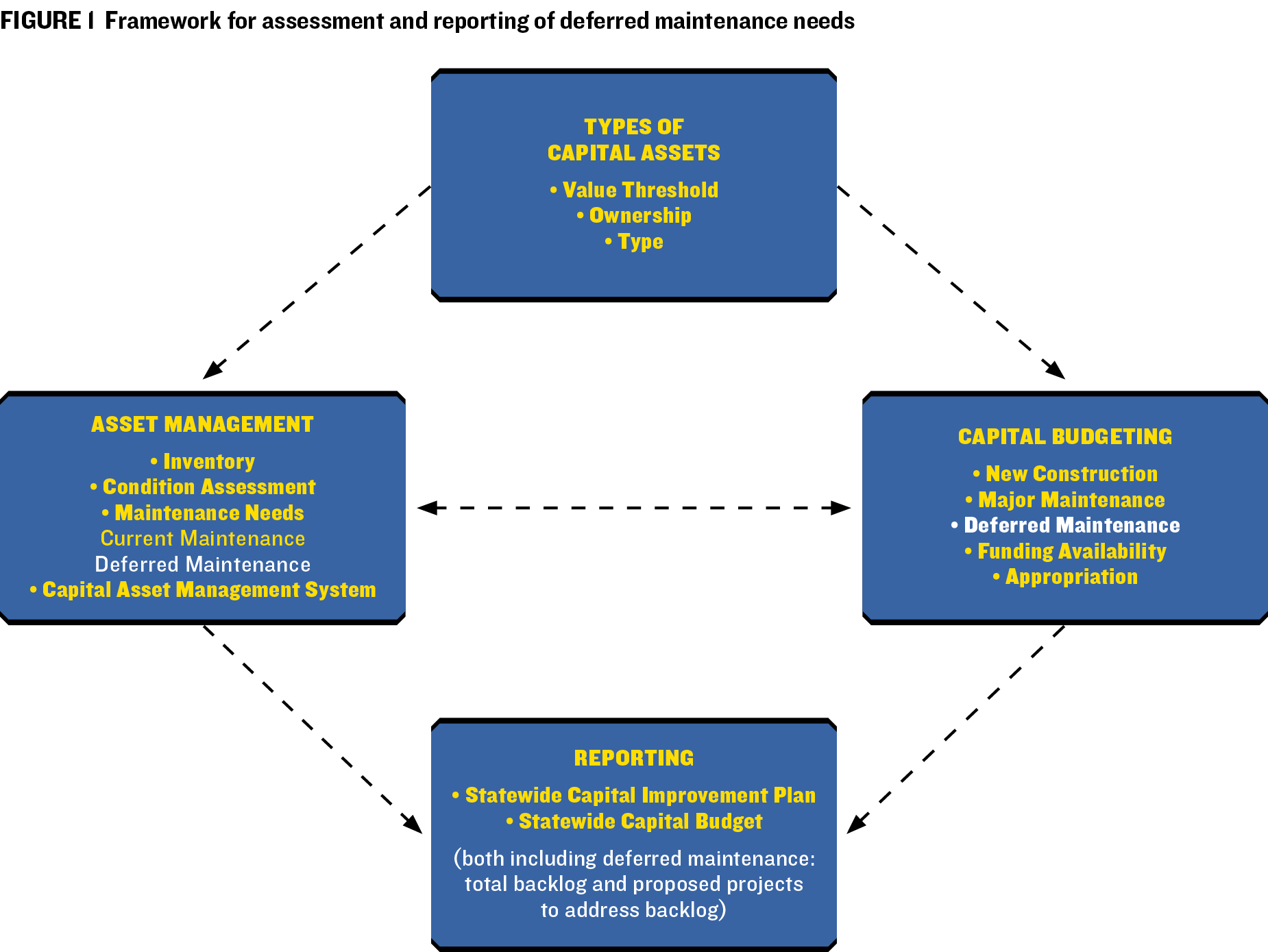

This tool kit is part of a broader research project on deferred infrastructure maintenance. Assessing and reporting deferred maintenance backlogs requires policies that guide processes (figure 1). Deferred maintenance needs should be identified as part of capital assets management processes, budgeted for in capital budgets, and clearly separated from construction and major maintenance projects. Furthermore, statewide capital budgets and statewide capital improvement plans should disclose total deferred maintenance backlogs, annual funding appropriated in the current year, and estimated funding required in future years.

ABOUT THIS TOOLKIT This is a guide that aims to assist states in adopting or improving the assessment and documentation of deferred infrastructure maintenance needs. It is organized into a series of modules, each focused on a component of a state's approach to deferred maintenance. States at the beginning of their efforts can use the tool kit as a road map for establishing foundational systems, while those with existing frameworks can identify opportunities to refine and enhance them. Each component offers key actions and real examples drawn from the experiences of states analyzed in this project.

MODULE 1 Establishing policy guidance on scope and agencies’ responsibilities

1.1 Maintaining consistent definitions of maintenance and deferred maintenance

1.2 Defining the types of infrastructure to be considered in the assessment and reporting of deferred maintenance needs

1. 3 Determining the agencies involved and their responsibilities

1. 4 Establishing policies that guide the assessment and reporting of deferred maintenance needs

Module 2 Assessing deferred maintenance and addressing funding needs

2. 1 Establishing procedures for assessing deferred maintenance needs

2.2 Adopting and implementing a methodology for selecting and prioritizing deferred maintenance projects for funding

2. 3 Establishing reliable and consistent funding allocation to address deferred maintenance needs

2. 4 Providing education to state agency staff about the deferred maintenance process

2. 5 Providing deferred maintenance education to legislation and executive staff

Module 3 Disclosing deferred maintenance needs and funding strategies

3.1 Reporting statewide deferred maintenance needs

3.2 Reporting funding appropriations to address deferred maintenance needs

MODULE 1: Establishing Policy Guidance on Scope and Agencies' Responsibilities

1.1. MAINTAINING CONSISTENT DEFINITIONS OF MAINTENANCE AND DEFERRED MAINTENANCE

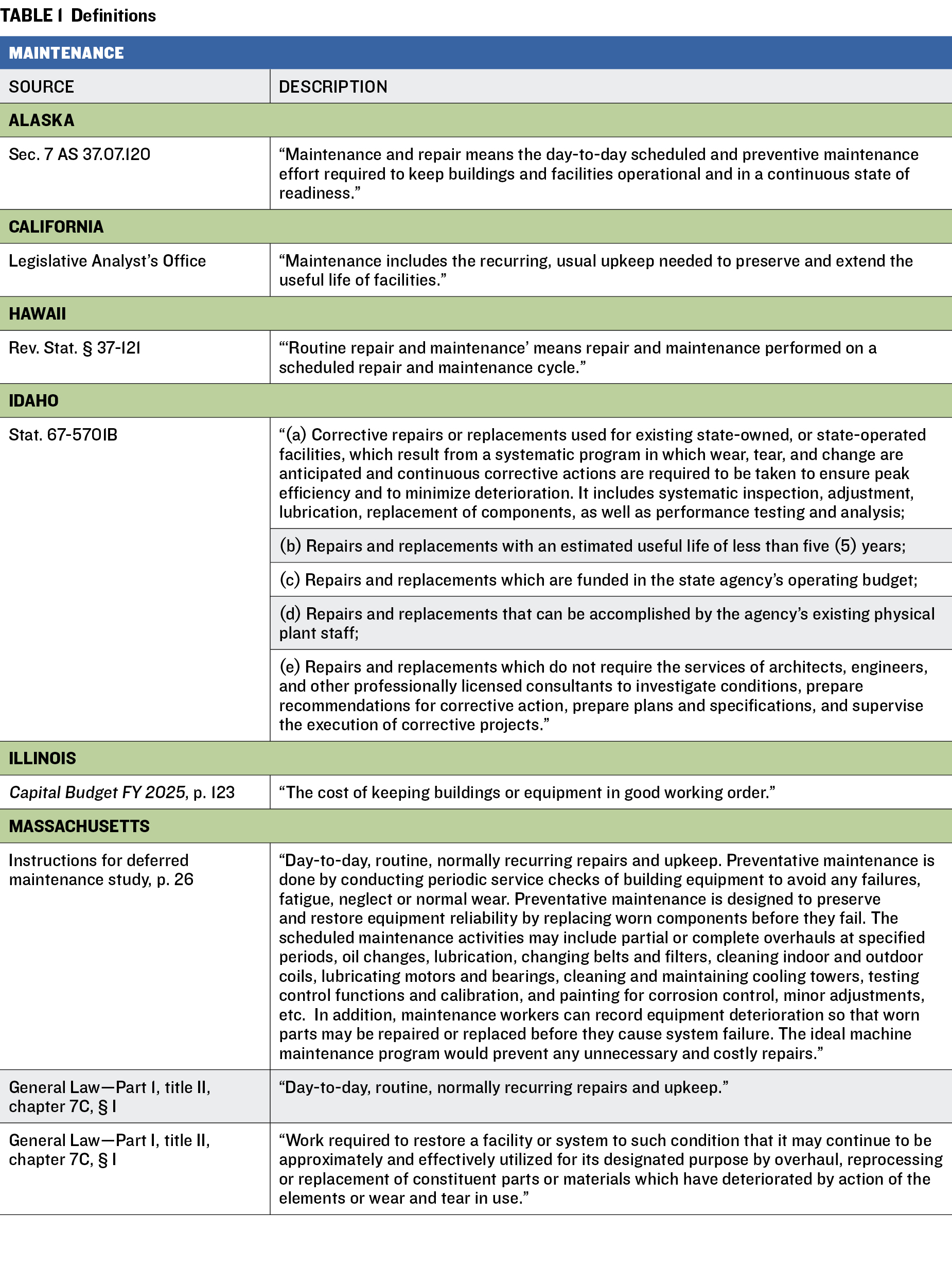

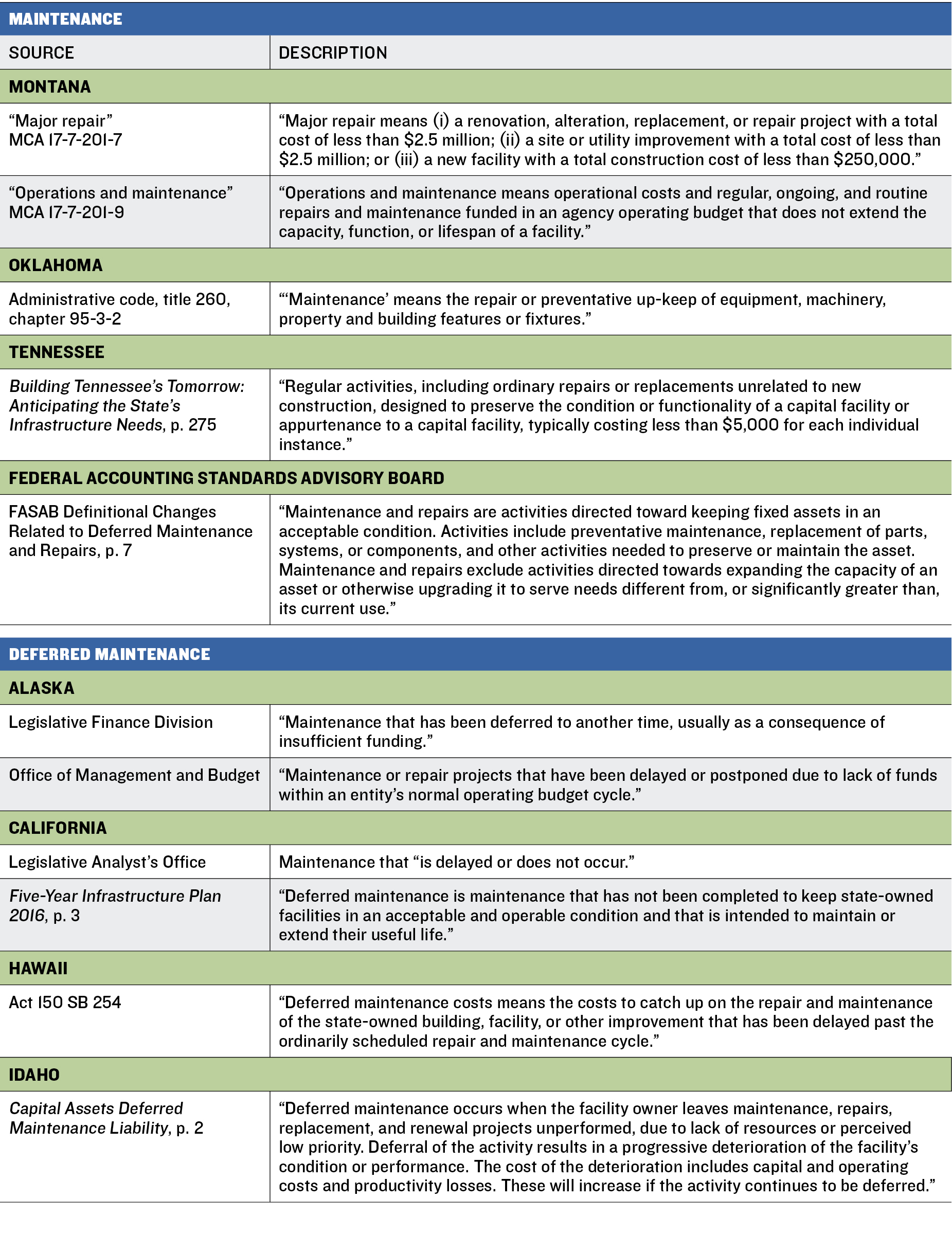

Clear and consistent definitions of maintenance and deferred maintenance are essential to clarify and avoid misunderstanding among stakeholders in assessing deferred maintenance needs. Standardizing and clearly documenting these definitions may aid consistent reporting of statewide deferred maintenance needs.

The terms deferred maintenance, deferred maintenance needs, deferred maintenance costs, deferred maintenance deficiencies, critical repairs, and deferred maintenance backlogs are generally used interchangeably. Regardless of which term is chosen, it is important that a state use it consistently across all documentation to ensure clarity and alignment.

The definition process should include the following:

REVIEWING HOW THE STATE DEFINES MAINTENANCE Maintenance usually refers to repairs that are recurrent and scheduled to preserve and extend functionality to keep infrastructure in good working order or acceptable condition. Hawaii defines it as the cost of catching up with delayed maintenance, which acknowledges additional costs incurred for not performing the maintenance that was due.

CLARIFYING THE PERIOD IN WHICH MAINTENANCE BECOMES DEFERRED A certain amount of maintenance should be provided in a given period and becomes deferred if not completed by the end of this period. The period can be determined by the repair and maintenance cycle (as in Hawaii) or by the operating budget cycle (as in Alaska).

SPECIFYING THE TYPES OF INFRASTRUCTURE CONSIDERED Define the scope of infrastructure included in the process and its ownership (see the next subsection).

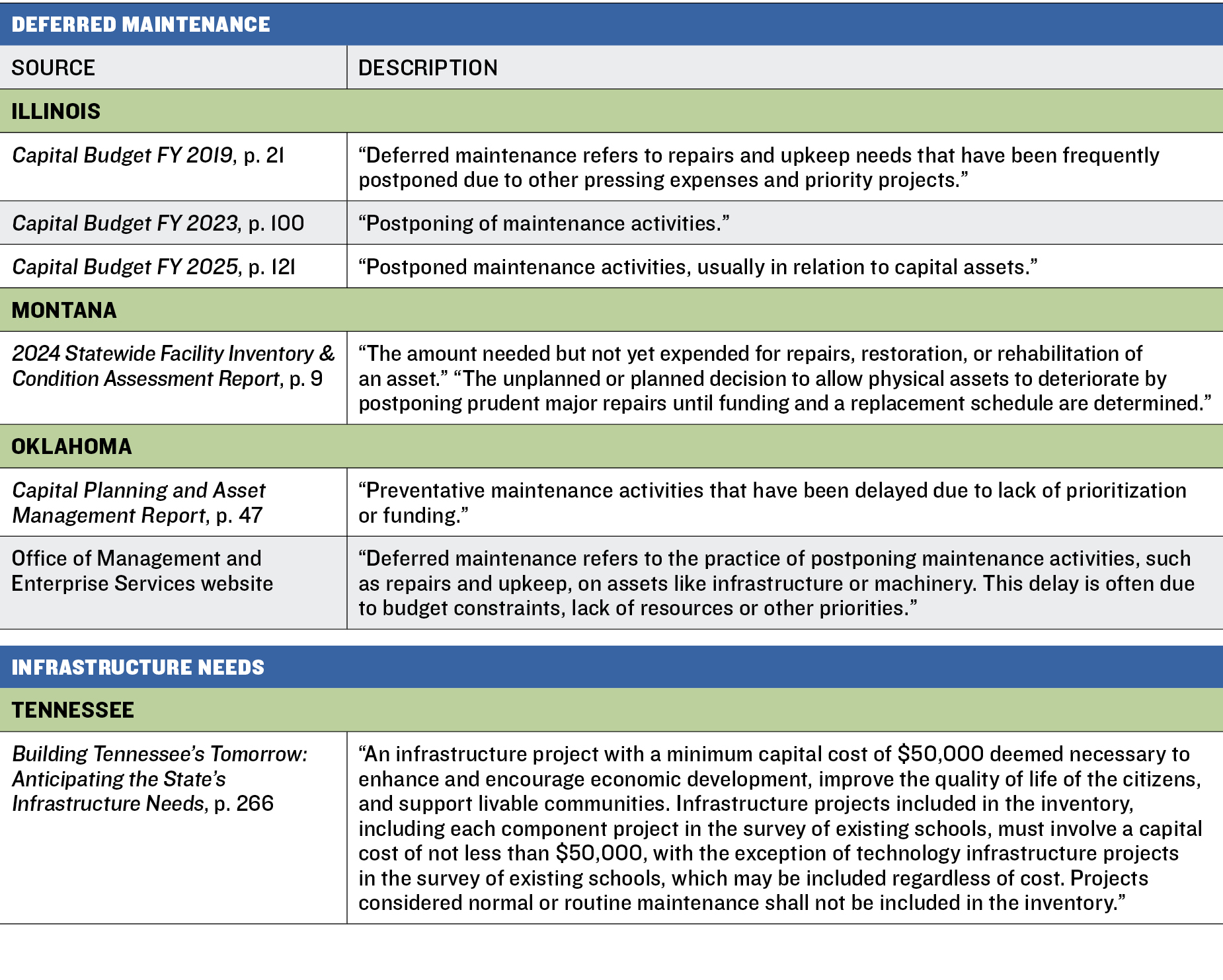

The definition of maintenance is generally included in state statutes, and the definition of deferred maintenance is often included only in documents reporting on deferred maintenance. Table 1 presents definitions of maintenance and deferred maintenance used by the states included in this study.

1.2. DEFINING THE TYPES OF INFRASTRUCTURE TO BE CONSIDERED IN THE ASSESSMENT AND REPORTING OF DEFERRED MAINTENANCE NEEDS

Defining the types of infrastructure to be considered for deferred maintenance assessment and reporting is an important step for establishing the processes for assessing and reporting deferred maintenance. It is crucial to determine the agencies involved in the process, their responsibilities, and the level of coordination required. These steps help improve the assessment and reporting processes, the accuracy of statewide deferred maintenance needs, and the appropriate funding.

Ideally, all types of infrastructure should be considered; in practice, state agencies must navigate several trade-offs. Different infrastructure categories may require tailored strategies for assessment criteria, time frames, or definitions of condition. It may be more effective for individual state agencies to manage and standardize their processes given the level of expertise needed. Conversely, for similar types of infrastructure—such as buildings—a centralized effort led by a single agency may be more efficient and consistent. Ultimately, the types of infrastructure considered in a statewide approach to address deferred maintenance will depend on factors such as staff capacity and budget constraints.

THE SCOPE OF COVERAGE OF THE INFRASTRUCTURE It ranges from a comprehensive approach, which encompasses all infrastructure assets, such as buildings, roads, structures, and equipment, to a narrower focus that encompasses only buildings or vertical infrastructure. Determining the scope involves making trade-offs. A comprehensive approach allows for a more holistic view of a state’s deferred maintenance needs but might be more costly to implement and more difficult to standardize across agencies, as different types of infrastructure have different life-cycle trajectories and ways to assess condition. Across selected case studies, those with a comprehensive infrastructure scope actually delegate maintenance activities and decisions to individual agencies. The lead agency in these cases collects information only for reporting. A narrow focus might be more manageable operationally and less complicated to standardize across state agencies.

THE OWNERSHIP OF THE INFRASTRUCTURE The ownership structure varies across case studies: state-owned, state-maintained and operated, or locality owned.

• State-owned infrastructure includes assets that are wholly owned by the state.

• State-maintained and operated infrastructure refers to assets that may be owned by another entity but are operated or maintained by the state.

• Locality-owned infrastructure refers to assets owned and maintained by local governments such as counties, cities, municipalities, or special districts.

THE SOURCE OF FUNDING THAT SUPPORTS THE INFRASTRUCTURE In capital budgeting, infrastructure may be funded by general revenues, special revenues (such as dedicated taxes or user fees), or the combination of both. The funding sources that support each type of infrastructure vary in each state. Across case studies, states with a comprehensive infrastructure scope often do not limit the types of infrastructure considered in the assessment of deferred maintenance, while states with a narrow scope of deferred maintenance may limit the infrastructure considered to infrastructure projects that receive funding from certain revenue sources. For this reason, in some states, transportation-related and university infrastructure are sometimes not included in the assessment of deferred maintenance.

THE COST OF THE INFRASTRUCTURE Across case studies, agencies limit the infrastructure considered in the process to those whose capital cost is above a certain threshold.

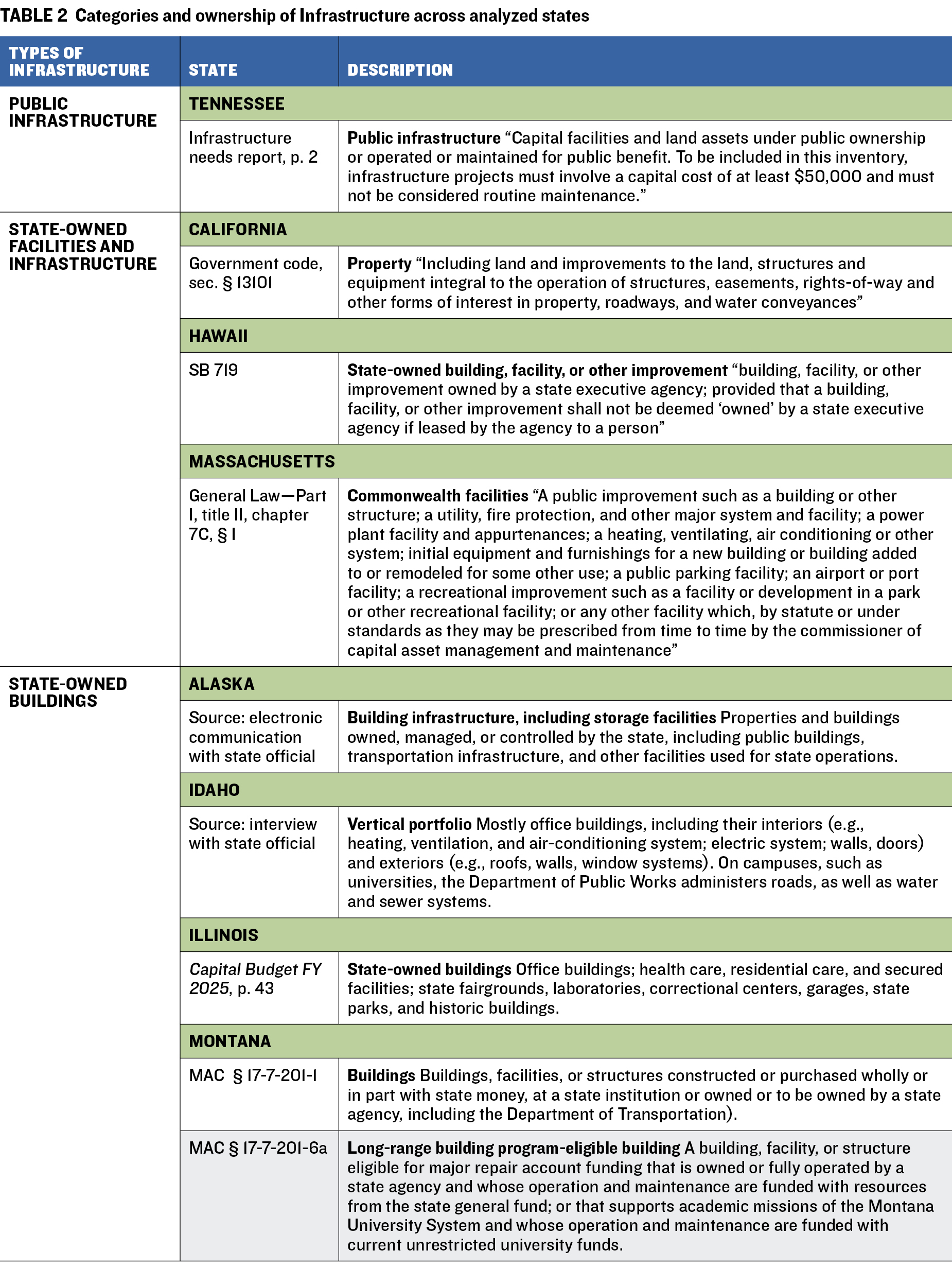

Table 2 provides examples of the types of infrastructure used among case studies.

1.3. DETERMINING THE AGENCIES INVOLVED AND THEIR RESPONSIBILITIES

Determining the agencies involved in assessing and reporting deferred maintenance needs and their roles and responsibilities contributes to compliance and accountability while reducing duplication of effort. The first step in this practice is identifying the relevant agencies. Once the types of infrastructure to be considered in the process are identified, determine which agencies own or manage these types of infrastructure.

The second step is defining each agency’s role and responsibility in assessing and reporting deferred maintenance needs. They will include evaluating the condition of infrastructure, developing and implementing a plan for addressing deferred maintenance needs, and prioritizing and reporting them. Other factors in determining agencies’ roles and responsibilities are staff capacity, capital management systems, and the level of standardization of the process.

1.4. ESTABLISHING POLICIES THAT GUIDE THE ASSESSMENT AND REPORTING OF DEFERRED MAINTENANCE

Statewide assessment and reporting of deferred maintenance requires policies that provide guidance in the process and delineate the responsibilities of the state agencies involved. These policies, typically established through legislation, provide a structural framework for data collection and reporting. They may also enhance accountability, transparency, and strategic planning in addressing deferred maintenance needs.

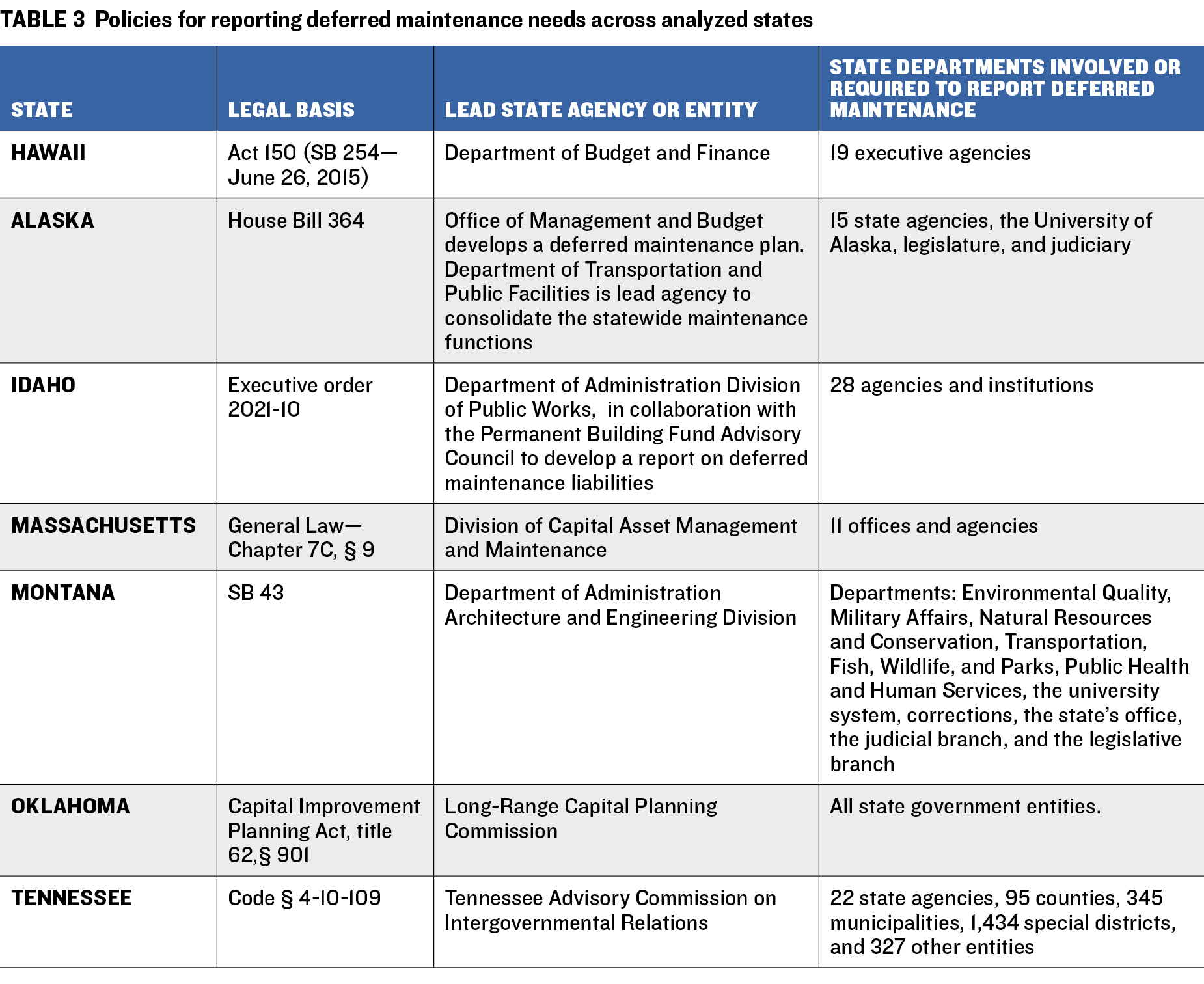

Existing policies generally describe the role of state agencies in the statewide collection and reporting of deferred maintenance needs. Policies typically designate a lead state agency or entity to oversee the collection and reporting of the state’s needs. Additionally, these policies specify the roles and responsibilities of other state agencies, which generally include a requirement to provide deferred maintenance information to the lead agency or entity. In a few states, the policy requires collaboration with the lead state agency or entity for the reporting of deferred maintenance needs or authorizes the lead agency to request information from other state agencies. Table 3 presents the policies used across selected states.

Additional considerations to include as part of the policy:

A. Lay out provisions detailing the level of standardization required for statewide procedures to collect and report on deferred maintenance needs. For example, Hawaii’s policy specifies that the Department of Budget and Finance is not required to ensure the accuracy of the information in the reports, while Tennessee requires the state Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations to implement standardized procedures to ensure ease and accuracy in summarizing statewide needs and costs.

B. Require the development of a plan to address deferred maintenance needs. Across analyzed states, common components of required plans include the following:

• Inventory of projects: Creating a list identifying deferred maintenance projects and condition of facilities

• A timeline or schedule to identify and address deferred maintenance needs

• Prioritization criteria: Defining and establishing criteria for project prioritization for funding allocation

• Funding: Identifying and planning for funding needed to address deferred maintenance needs

• Regular updates: Requiring updates to the plan to help ensure that it is current and actionable

C. Require the reporting of deferred maintenance needs in a designated document. For instance, Hawaii requires reporting in its multiyear program, financial plan, executive budget documents, and supplemental budget. Similarly, Idaho requires a report on state deferred maintenance liabilities.

MODULE 2: Assessing Deferred Maintenance and Addressing Funding Needs

DEFERRED MAINTENANCE NEEDS should be assessed, communicated and funded consistently. This module will address the following questions:

WHAT TYPES OF PROCEDURES SHOULD BE DEFINED FOR ASSESSING DEFERRED MAINTENANCE NEEDS? Establishing clear and standardized procedures for assessing deferred maintenance needs helps ensure that the infrastructure is properly maintained and that necessary repairs or replacements are identified before they become critical issues. Important procedures identified across analyzed states include inventorying the different types of infrastructure; conducting an assessment of the condition of assets identified in the inventory; performing supplemental analyses to determine appropriate actions to address deferred maintenance needs; and collecting, recording, and reporting data on infrastructure condition to support decision-making and long-term planning.

HOW SHOULD DEFERRED MAINTENANCE PROJECTS BE PRIORITIZED FOR FUNDING? Due to growing deferred maintenance needs and limited funding, some states have developed prioritization frameworks to guide decisions on which deferred maintenance projects should receive funding. These frameworks incorporate a range of quantitative and qualitative criteria aligned with state-specific priorities. They also facilitate the efficient allocation of resources, ensuring that the most urgent and high-impact needs are addressed first.

WHAT ARE THE FUNDING SOURCES TO ADDRESS DEFERRED MAINTENANCE NEEDS? States rely on a variety of funding sources to address deferred maintenance needs, including capital budget funds, general funds, and bond financing. It is essential that these funding mechanisms are reliable and consistent to prevent further infrastructure deterioration, minimize the long-term costs of delayed repairs, and ensure the continued delivery of public services.

HOW CAN THE PROCESS BE STREAMLINED FOR STATE AGENCIES AND FOR LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE STAFF? Streamlining the process of assessing deferred maintenance requires clear communication, coordination, and capacity-building. Training is an important tool in aligning the understanding and priorities of multiple state agencies, legislative staff, and executive leadership. Providing well-structured resources to all stakeholders involved in the process helps build understanding, support informed decision-making, and unify the approach to managing deferred maintenance needs.

2.1. Establishing procedures for assessing deferred maintenance needs

The procedures used to assess deferred maintenance needs are generally part of state agencies’ capital asset management practices. Establishing clear and consistent procedures helps ensure that the infrastructure is properly maintained and aids in identifying necessary repairs or replacements before they become critical issues. Among analyzed states, the process typically involves the following steps:

INVENTORYING TYPES OF INFRASTRUCTURE Lead agencies in charge of maintaining a statewide infrastructure inventory may aggregate existing from individual agencies or enhance and adjust data collected by agencies that already have a statewide list of assets for other infrastructure management–related purposes, such as insurance. For example, Montana officials have relied on data from the Risk Management and Tort Defense Division of the Department of Administration, which has kept a central roster of state-owned facilities for insurance purposes.

The information provided in such inventories includes

- Name or identifier of the infrastructure

- Area (such as acres or square feet)

- Location (latitude and longitude)

- Asset condition (excellent, good, fair, poor)

Examples of inventories available to the public include Montana’s 2024 Statewide Facility Inventory & Condition Assessment Report, Oklahoma’s 2024 Real Property Asset Report, and Building Tennessee’s Tomorrow (for July 2022 through June 2027).

CONDUCTING FACILITY CONDITION ASSESSMENT Staff or external contractors conduct a comprehensive and physical infrastructure assessment to identify deferred maintenance, capital renewal, and replacement projects.

The infrastructure components typically inspected include roofs; building exteriors; elevators; heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC; equipment and distribution system); equipment (electrical and fire protection equipment); interior finishes; vertical and horizontal elements; site development; and utility systems.

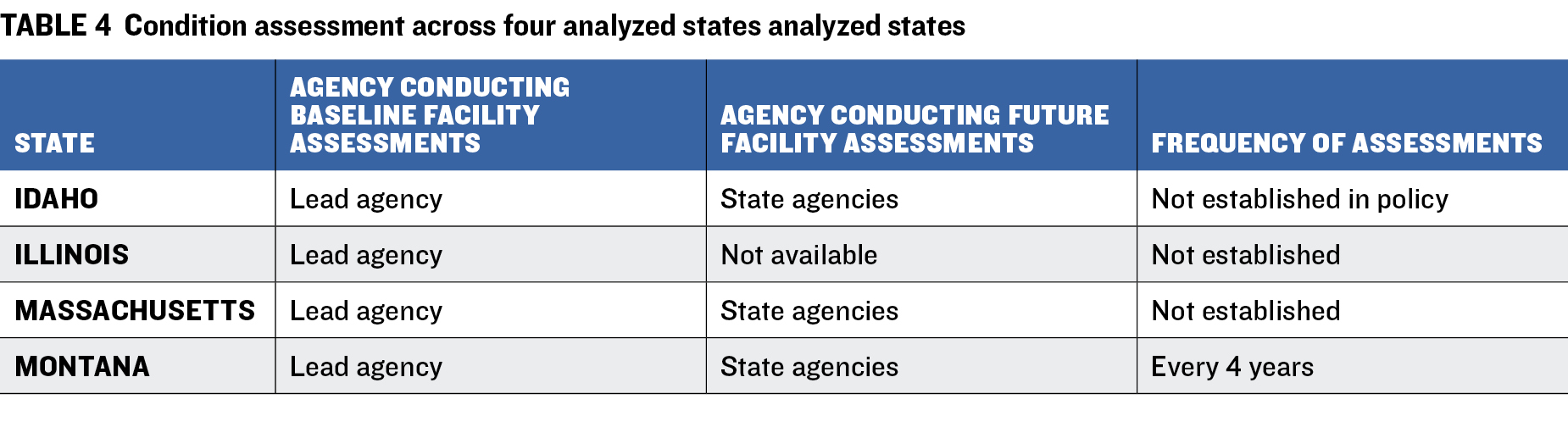

A baseline assessment is typically performed or contracted out by the lead agency for consistency of data across all agencies and comparability across state agencies and to ensure that the evaluations are not biased. Any assessments following the baseline evaluation are typically the responsibility of state agencies and should be required to be updated regularly to reflect the current condition of the infrastructure. Table 4 presents information on condition assessments conducted across four analyzed states.

DETERMINING ACTIONS TO ADDRESS DEFERRED MAINTENANCE NEEDS After assessing the infrastructure condition, state agency staff should conduct additional analysis to determine deferred maintenance needs. Infrastructure in poor condition might have become too expensive to maintain. In such cases, agencies should perform a life-cycle cost analysis (LCCA) to determine which action is more beneficial: completing deferred maintenance repairs or replacing the infrastructure. States already conducting LCCA include Idaho and Oklahoma.

In addition to conducting such an analysis, state agency staff should publish a list of the types of infrastructure that are removed from service or disposed of and the cost of replacement, as these items will likely change the year-to-year value of deferred maintenance needs.

COLLECTING, RECORDING, AND REPORTING INFRASTRUCTURE INFORMATION Staff should gather details from the assessment and enter it into a capital asset management system. Such a system is designed to manage, track, share, and report on the status of the infrastructure.

Information commonly collected in these systems includes:

- Age

- Location

- Area

- Expected life and expected remaining life

- Maintenance history

- Infrastructure components

- Building (e.g., roof, exteriors, internal spaces)

- Systems (e.g., electric, HVAC, plumbing)

- Cost estimates

- Incident or accident reports

These systems often have embedded capabilities to calculate metrics that disclose the condition of the infrastructure (e.g., the facilities condition index, or FCI, estimated deferred maintenance) that are used to inform decision-making.

State agencies also use these systems in their budgeting processes and incorporate other infrastructure-related information such as usage, code requirements (to monitor compliance and violations), energy efficiency, and climate change resiliency (e.g., flood mitigation, extreme heat management). Similarly, these systems contain information for prioritizing needs such as the criticality of the infrastructure’s condition and the risks it represents for users.

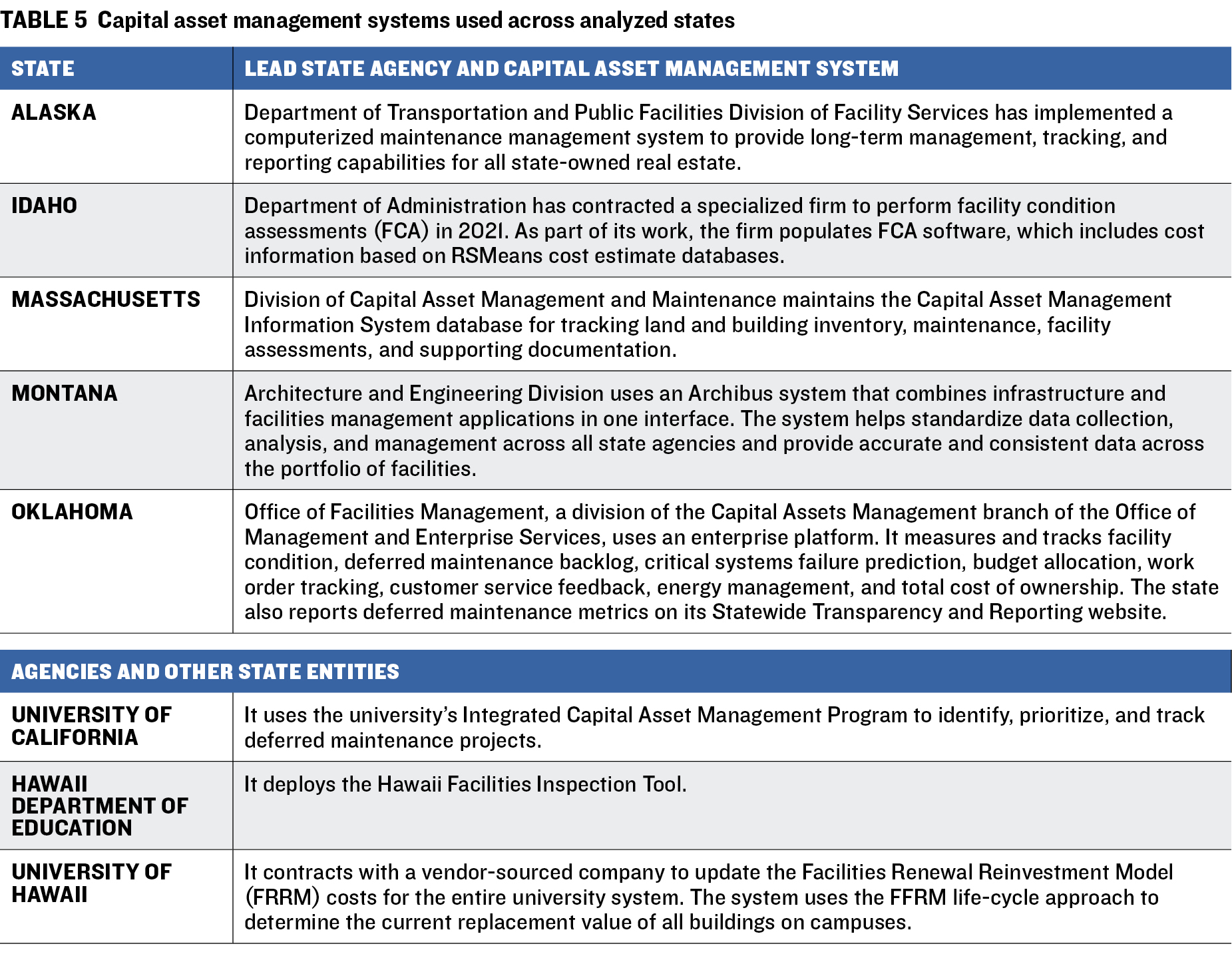

Information in these systems is typically updated every year. Having the most accurate and current data helps agencies maintain a reliable inventory of their needs and facilitates decision-making. Table 5 presents the capital asset management system used across analyzed states. The information in these systems is for internal use, and only agency staff has access to it. But several states make some of the information available to the public.

2.2. Adopting and implementing a methodology for selecting and prioritizing deferred maintenance projects for capital budget decisions and funding

Due to the increasing and pressing deferred maintenance needs and the limited funding available to address them, agencies have adopted various methodologies for prioritizing needs to allocate funding that could also be used for capital budgeting decision-making.

APPROACH The approach to prioritizing deferred maintenance needs typically depends on the types of infrastructure considered. Two common approaches are

- Individual agency, in which individual state agencies prioritize deferred maintenance needs for their owned or managed assets according to goals, objectives, and needs

- Statewide, in which lead state agencies prioritize deferred maintenance needs according to statewide goals and objectives across all covered assets

METHODS The following are three methods for prioritizing deferred maintenance needs:

- Data-driven method: The prioritization relies on technical metrics derived from capital asset management systems (such as the FCI) that quantitatively assess the condition of the infrastructure to determine which needs must be addressed first.

- Collective deliberation-driven method: A group of agency staff subjectively assesses the criticality or urgency of deferred maintenance needs. Each need may be considered separately and in relation to the larger system.

- Hybrid method: A combination of the two previous methods. The decision process may weight both methods to align with statewide goals and objectives.

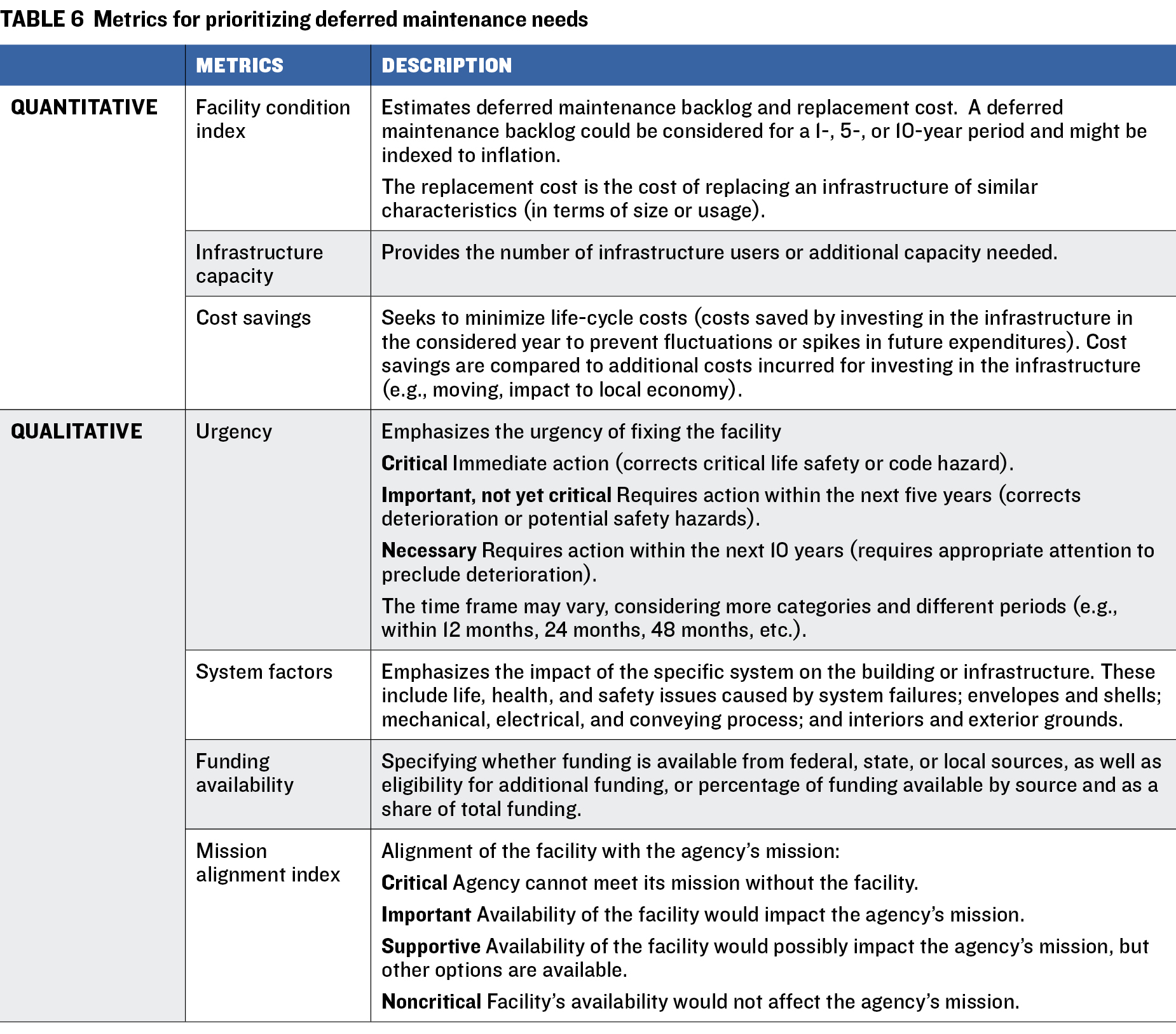

METRICS Various qualitative and quantitative metrics are used to prioritize deferred maintenance needs for funding. These metrics help assess the condition, severity, urgency, and impact of such a need. Examples of commonly used metrics are referenced in table 6.

These are among states using a statewide prioritization process:

- Alaska

- Idaho

- Massachusetts

- Oklahoma

2.3. Establishing reliable and consistent funding allocations to address deferred maintenance needs

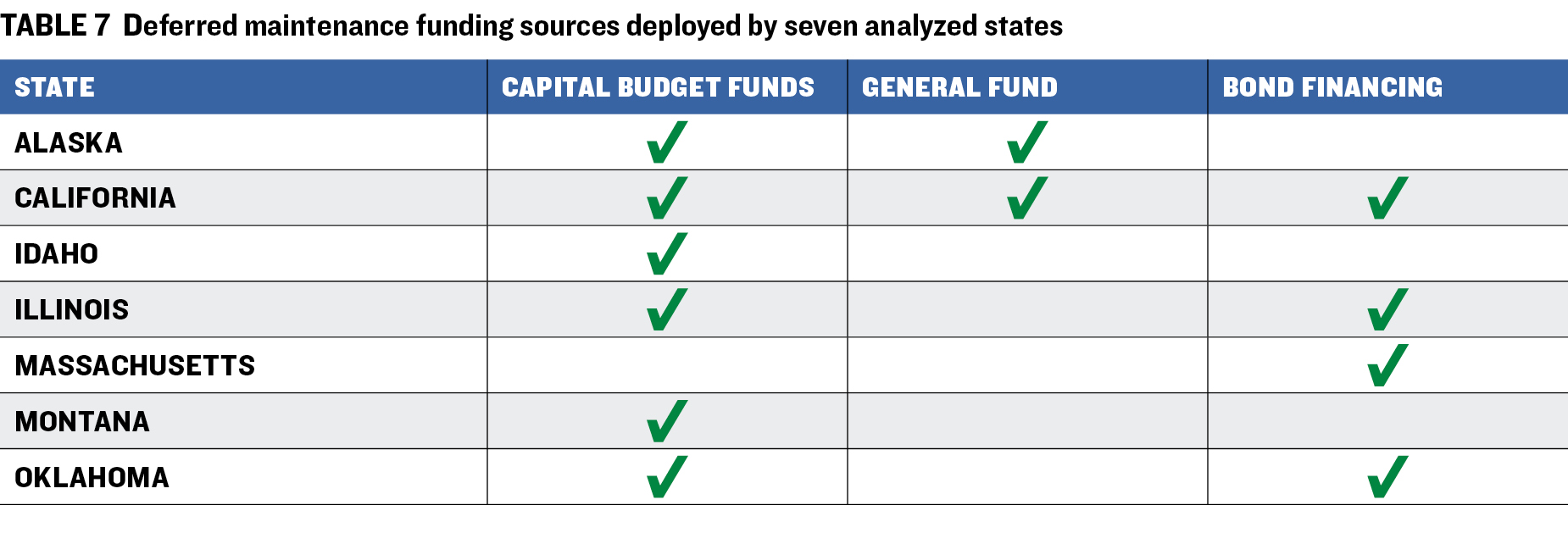

Establishing reliable and consistent funding allocations to address deferred maintenance needs is essential to prevent further infrastructure deterioration, reduce costs of future repairs, and support the delivery of public services. Analyzed states often rely on a combination of funding sources, including capital budget funds, general funds, and bond financing.

CAPITAL BUDGET FUNDS These are primary special revenue funds that are supplemented occasionally with transfers from the general fund. Five of the nine analyzed states have established these funds to address the lack of a dedicated funding stream for deferred maintenance and the change in priorities between administrators and legislators. These funds provide a more stable way for states to pay for deferred maintenance, particularly given possible changes of elected officials and agency leadership.

The Alaska legislature established the Alaska Capital Income Fund to provide dollars for preventive or deferred maintenance of facilities. It is capitalized by an annual appropriation of earnings from the Alaska Permanent Fund.

Idaho uses appropriations from the Permanent Building Fund (PBF), which receives transfers from sales; income, cigarette, and beer taxes; state lottery earnings; general fund; and interest earnings from the PBF and budget stabilization fund.

Illinois established Rebuild Illinois, a program that is funded by revenues from licenses, admission taxes, and fees from casinos, gambling, and video gaming; cigarette tax revenues; parking excise collections; trade-in property; taxes on out-of-state retailers; and transportation-related taxes.

Montana uses the major repair account within the Long-Range Building Program. The account receives funding from the cigarette and the coal severance tax, along with interest earnings, project carryover funds, administrative fees, miscellaneous revenues, and transfers from the general fund. Additional funding for deferred maintenance comes from the capital developments account—also part of the Long-Range Building Program—which receives dollars from annual transfers from the general fund proposed by the governor. Montana also recently created a working rainy day fund, which receives transfers from the Budget Stabilization Reserve Fund under specific economic circumstances.

Oklahoma has the Maintenance of State Buildings Revolving Fund, which is stocked with proceeds of sales of state-owned buildings and annual and one-time legislative appropriations. In addition, the state created the Legacy Capital Financing Fund to provide loans for the state’s capital needs. Loans are interest-free, must be paid over a 20-year term, and lack the issuance costs of a bond offering.

In addition to these statewide funds, states have established programs with specific objectives and timelines to address deferred maintenance in particular state agencies. For example, California’s Road Maintenance and Rehabilitation Program and Drought, Water, Parks, Climate, Coastal Protection and Outdoor Access for All Act provide funding for deferred maintenance in the transportation and park system, respectively. And the Statewide Montana Accelerate Rapid Training (SMART) deferred maintenance program provides funding for those needs for Department of Military Affairs facilities.

GENERAL FUND California and Idaho have used one-time allocations from their general funds. Similarly, the Alaska Public Building Fund—a special account in the general fund—can be tapped to address deferred maintenance needs.

BOND FINANCING California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and Oklahoma have used bond proceeds for their deferred maintenance needs.

Table 7 presents the combinations of funding sources that analyzed states use to address deferred maintenance needs.

Preventing the accumulation of deferred maintenance

2.4. Providing education about the deferred maintenance process to state agency staff

Several case studies highlight the importance of educating staff across all agencies involved about the deferred maintenance assessment and reporting process. This ensures a clear understanding of the procedures and systems available for addressing deferred maintenance needs, contributes to standardizing the reporting process, ensures uniformity across agencies, and promotes the accuracy and relevance of data entered into the systems.

The educational materials should be made accessible via the lead agency’s website and updated annually to reflect system changes. Across analyzed states, educational materials include

INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS AND FORM TEMPLATES Instructional materials are stand-alone documents or communications that are available on websites or are sent to all agencies responsible for providing deferred maintenance information that provide guidance about the processes or the information required. These often come with form templates: predesigned documents used to collect or organize information in a structured way. Both instructional materials and form templates contribute to standardizing the reporting process, ensuring uniformity and comparability across agencies, and fostering transparency and accountability. In addition, they are practical tools—especially for agencies with limited resources or technical expertise—that enable agencies to align with statewide goals and methodologies more effectively.

In Hawaii, the budget instructions include an Additional Requirements section that provides guidelines for disclosing deferred maintenance needs. State departments responsible for operating and maintaining state-owned buildings must complete and submit a Form DMC (Department Summary of Estimated Deferred Maintenance Costs). Essential information such as the identification and organization code of the responsible program, the island location of the deferred maintenance cost, the type of asset (including name of building, facility, or improvement), description of the deferred maintenance cost, and the estimated amount and means of financing of each deferred maintenance cost.

In Massachusetts, the Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) requires that a study be submitted for the certification of a deferred maintenance project. The DCAMM website provides a template for the study and instructions for preparing and submitting it.

In Tennessee, state agencies receive an email requesting capital budget requests and infrastructure needs identified for a 20-year period. To collect data on local infrastructure needs, staff of each state development district surveys public officials within their jurisdictions, following directions from the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. Local needs are reported via the Existing School Facility Needs Inventory Form and the General Public Infrastructure Needs Inventory Form.

WEBINARS These are live, interactive online presentations that provide guidance on the deferred maintenance process and updates to the system. They use visual aids to enhance learning, and the format enables staff from state agencies to engage in the conversation from different locations. Lead agencies generally record these webinars and make them available on their websites for staff wishing to review the material or unable to attend the live session.

In Massachusetts, the DCAMM develops several webinars annually that discuss aspects of the deferred maintenance process. The webinars, 30–60 minutes long, cover topics such as requesting, oversight, and finance (“Deferred maintenance FY23 process”), as well as supporting resources (“Delegated project checklist and “Updated for study template”). DCAMM makes webinars and training materials available on its deferred maintenance web page.

TRAINING AND INFORMATION SESSIONS These are in-person listening sessions that provide guidance on the deferred maintenance process and updates to the system. These sessions enable only on-site staff to engage in conversations and are not recorded. Oklahoma is in the process of developing annual sessions focusing on capital asset management. An additional session will be planned when an impactful improvement is made.

2.5. Provide deferred maintenance education to legislative and executive staff

It is crucial to educate legislative and executive staff about deferred maintenance needs, as they play key roles in setting budgets and approving plans to address identified deferred maintenance needs. Increasing awareness about those needs before infrastructure fails helps avoid emergencies and associated high outlays. In addition, regularly informing leadership about the risks and long-term costs of deferring maintenance can assist in decision-making that is based on a clear understanding of the problem. Such communication can also enhance cross-agency coordination and planning, as well as efficient allocation of resources.

Such sessions could be integrated into budget hearings or held as briefings dedicated to deferred maintenance. In Alaska, the directors of the Office of Management and Budget and Department of Transportation and Public Facilities give annual presentations to the Senate and House Finance Committees about the approach for addressing deferred maintenance and current backlogs. California is considering a similar strategy.

Module 3: Disclosing Deferred Maintenance Needs and Funding Strategies

3.1. Reporting statewide deferred maintenance needs

States should present accumulated deferred maintenance needs in existing budget documents as a single section. The section should include the following items:

a. The state’s plans to consistently fund maintenance activities and prevent them from being deferred. Several analyzed states have identified this item as a top priority in policy and planning agendas.

b. Current deferred maintenance needs and year-to-year variations by state agencies and statewide totals. Analyzed states disclose maintenance needs, but a few report annual variations in their documents.

c. Appropriations requested by state agencies and statewide totals to address needs. Analyzed states currently disclosing their needs in budget documents also disclose the funding requests.

d. Information on the adequacy of requested and actual appropriations to address deferred maintenance, including for prior years. This information should include the following points:

1. If the resources are sufficient to cover maintenance expenditures (percentage of expenditures covered with funding requests and appropriations) and prevent the increase of deferred maintenance.

2. If the resources are sufficient to address maintenance backlogs (percentage of deferred maintenance needs covered with funding requests and appropriations).

If available, projections of future deferred maintenance given current or expected funding levels. None of the analyzed states currently follows this practice.

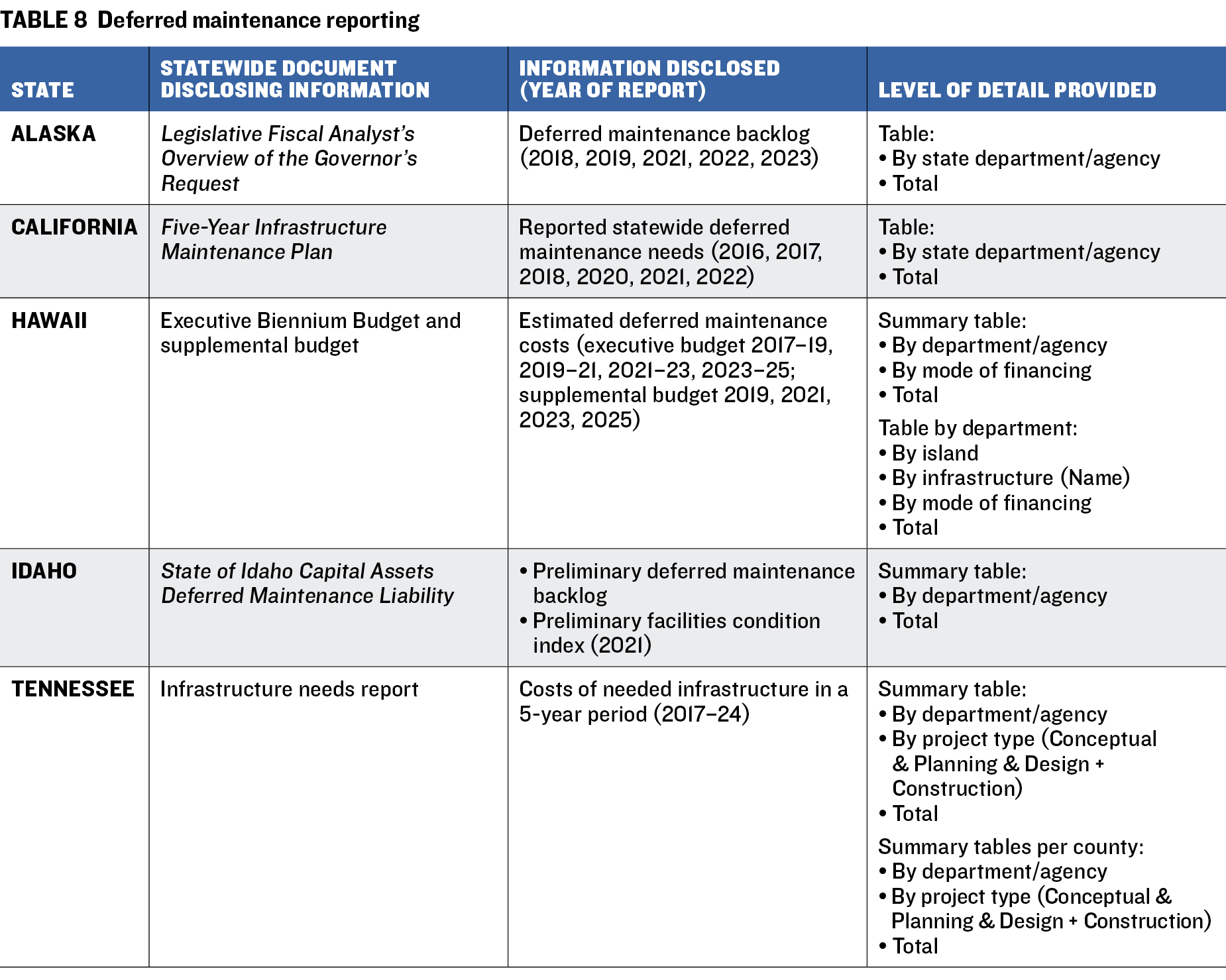

e. Other methods that affect the value of deferred maintenance needs (such as infrastructure that is removed from service or disposed of). None of the analyzed states currently utilizes this practice. Table 8 presents the reports used by five analyzed states to report deferred maintenance needs and a description of the level of detail provided. The states typically report deferred maintenance needs in a table that discloses needs by department and presents the total amount of deferred maintenance for the year of reporting.

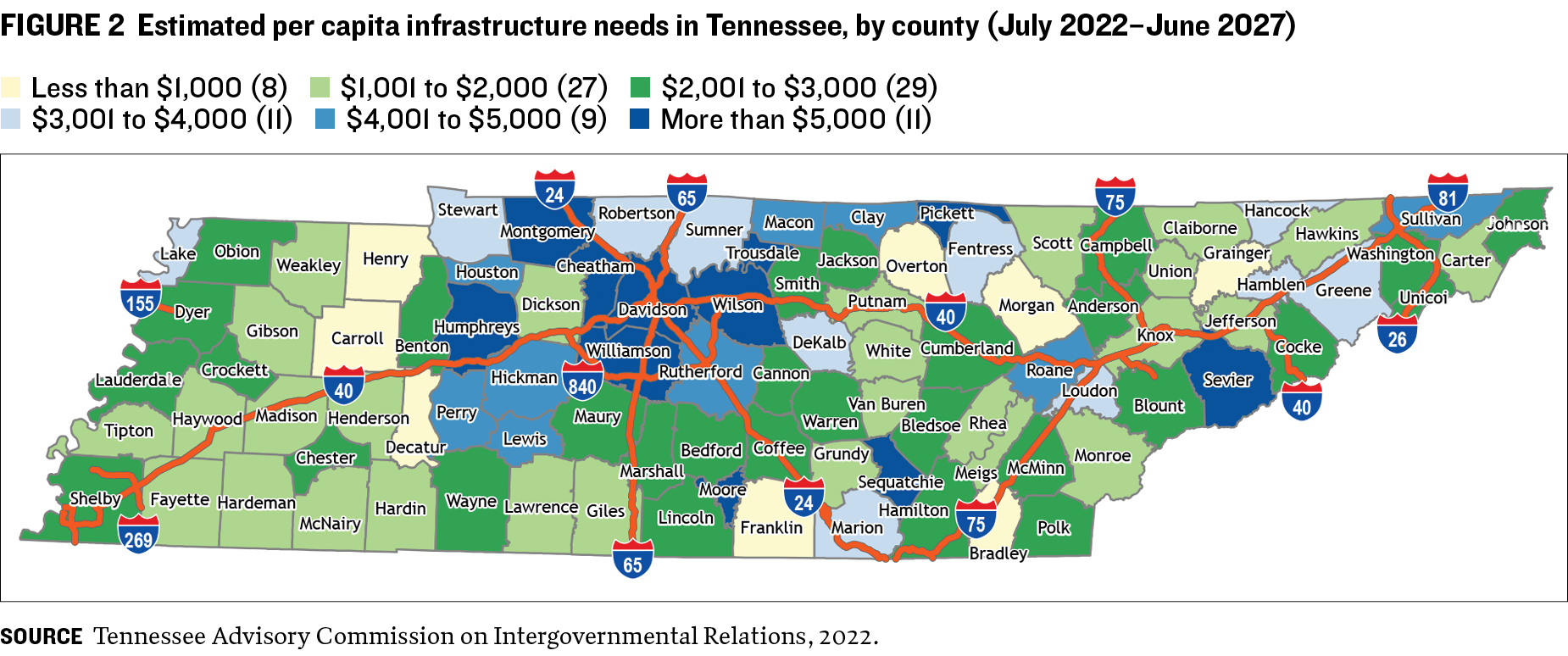

In addition to this information, states should consider disclosing needs by geographic area. Several are already including some geographic information in their reports. For instance, Hawaii discloses the island where the deferred maintenance need is located but does not report the total deferred maintenance costs by island. Similarly, Tennessee discloses infrastructure needs by county (as required per policy) in a table format (that includes county totals) and a visual representation (of both total needs and per capita needs—figure 2).

3.2. Reporting funding appropriated to address deferred maintenance needs

In addition to reporting the requests to fund deferred maintenance, states should disclose the actual amount of resources that are appropriated every year to meet deferred maintenance needs. This information is important to monitor progress in addressing existing needs and to assess or improve capital asset management strategies. In addition, it contributes to improving budgeting transparency.

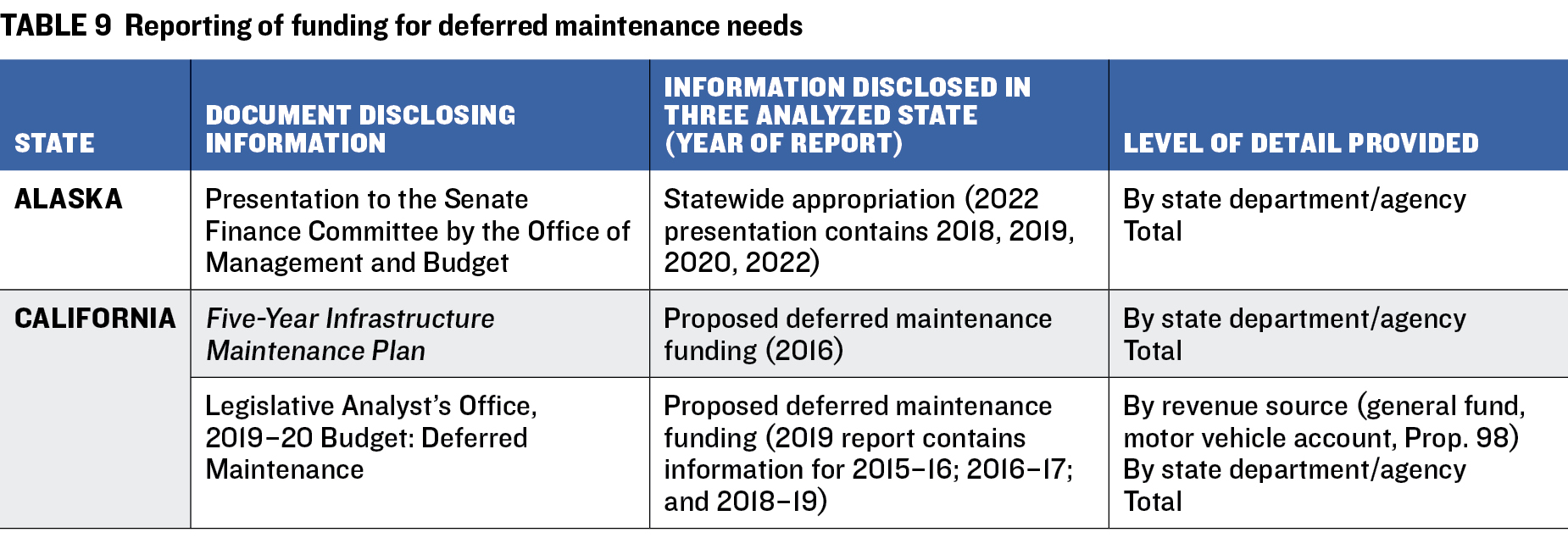

Across the states analyzed, a different state agency than the one responsible for collecting deferred maintenance needs is the one disclosing funding appropriated to address deferred maintenance needs. These reports typically include the total amount of resources appropriated, revenue sources for such appropriations, and a breakdown of resources by state agency. Table 9 lists the reports used by analyzed states to report such appropriations and a description of the level of detail provided.

Conclusion

This tool kit, informed by the experiences of nine states, provides practical guidance for state officials working to establish or improve systems for identifying, managing, and funding deferred maintenance. Whether a state is just beginning to address its backlog or refining an existing process, this material offers adaptable strategies and real-world examples to support progress.

Better tools are needed because deferred maintenance represents substantial financial and operational risks for state governments. Despite its magnitude—estimated at more than $1 trillion nationwide—deferred maintenance remains largely absent as liabilities on government balance sheets and is frequently underreported in capital budgeting documents. This lack of visibility affects strategic planning, increases long-term costs, and in some cases compromises public safety.

Along with better identification and tools, addressing deferred maintenance requires stronger leadership, heavier investment, and more interagency coordination. This tool kit will assist states in taking important first steps toward these goals and efforts to build more transparent and accountable infrastructure systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research team extends its gratitude to the state officials in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Massachusetts, Montana, and Tennessee who generously shared their time and expertise in responding to questions for the case study, both through interviews and written communications. Their thoughtful contributions were invaluable for our understanding of how they assess deferred maintenance needs in their states and thus for shaping the findings of this study. The research team also extends its gratitude to all state officials and transportation officials who generously shared their time and expertise in responding to questions in the fifty-state survey.

The research team wishes to thank Kaitlyn Freeman and Merlene-Patrice Quispe for their valuable assistance in gathering critical information for several of the case studies, and to Wenqi Zhao for his assistance in gathering information for the fifty-state review. Their support was important to the successful completion of the project.

The research team wishes to thank the staff members at the Volcker Alliance who provided us with invaluable support and advice:

Noah Winn-Ritzenberg, Senior Director, Public Finance

William Glasgall, Public Finance Adviser

Graham Dowd, Program Manager

Nathalia Trujillo, Associate Director, Public Finance

Divine Adeniyi, Program Assistant, Public Finance

Melissa Austin, Chief Operating Officer

Idalis Foster, Communications Manager

This report was supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts. The findings and recommendations are not necessarily endorsed by the supporting organization(s). The research team would like to extend gratitude to David Draine, Fatima Yousofi, Andrea Wales, Emma Wei, Aleena Oberthur, Mary Murphy, Corryn Hall, and Sara Dube of The Pew Charitable Trusts for their contributions to this report.

© 2025 VOLCKER ALLIANCE INC.

Published October, 2025

The Volcker Alliance Inc. hereby grants a worldwide, royalty-free, non-sublicensable, non-exclusive license to download and distribute the Volcker Alliance paper titled Meeting the Trillion-Dollar Challenge: Framework for Assessing and Reporting State Deferred Infrastructure Maintenance Needs (the “Paper”) for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the Paper’s copyright notice and this legend are included on all copies.

This paper was published by the Volcker Alliance as part of its Capital Budgeting and State Deferred Maintenance project. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Volcker Alliance. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Don Besom, art director.