Meeting the Trillion-Dollar Challenge: Case Studies

Deferred Infrastructure Maintenance Practices Across Ten States

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

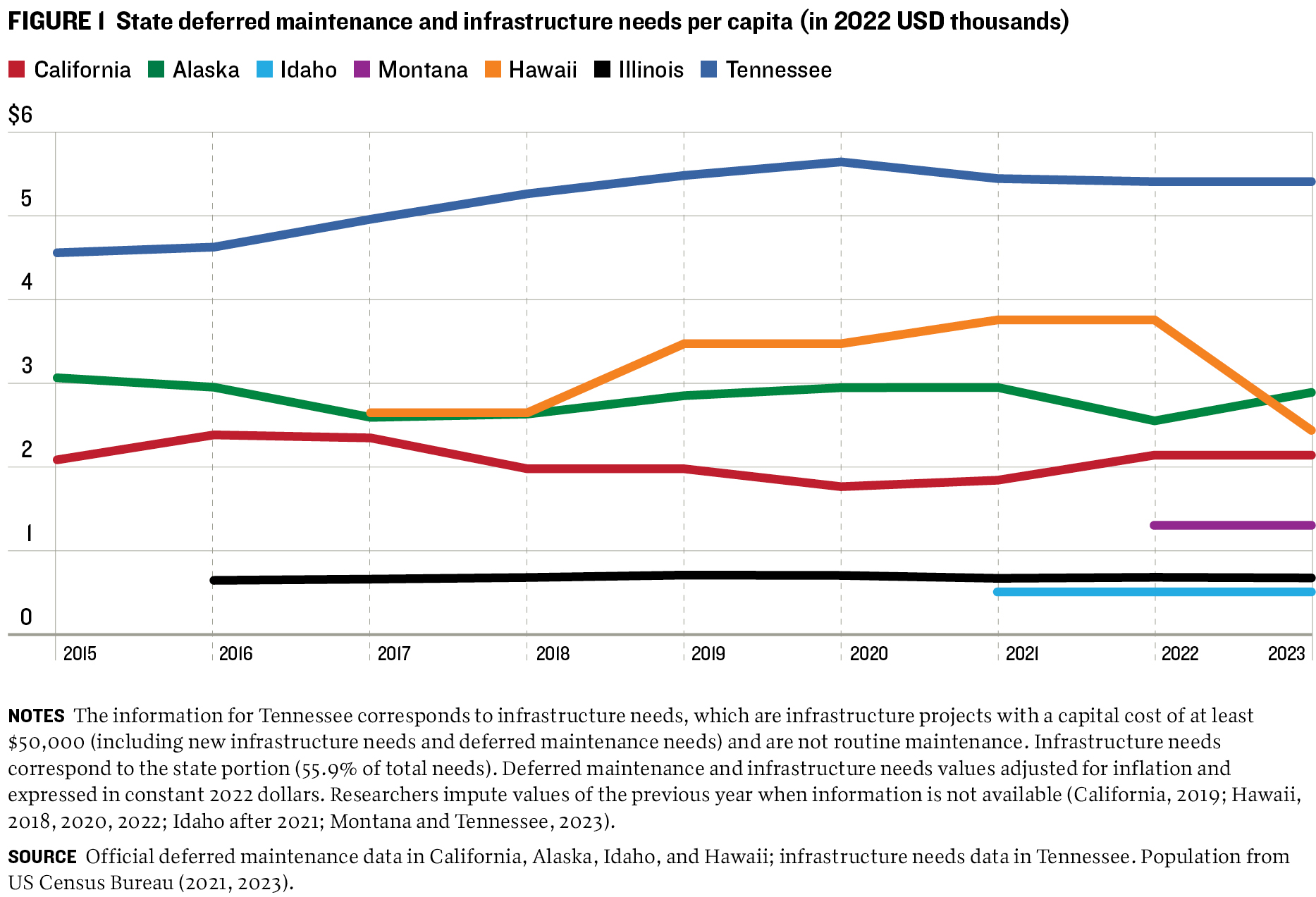

Publicly owned infrastructure in the US is in a poor state of repair, with an estimated $1 trillion in accumulated deferred maintenance across states.1 Budget constraints and competing priorities often lead government agencies to postpone or delay planned maintenance to make funds available for other pressing needs. This failure to keep up with repairs results in increased long-term maintenance expenditures, and, in some cases, compromises public safety and health. Despite the growing concern, few states report deferred maintenance needs in their capital budgeting documents, and no comprehensive statewide system exists to assess, value, and fund the infrastructure gap.

However, nine states—Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Montana, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania—have implemented statewide efforts to assess and address deferred maintenance. This study explores their policies and methodologies for reporting, valuing, and funding their deferred maintenance needs. We also examine policies in Tennessee, which has reported infrastructure needs for decades, including new construction and deferred maintenance. While it does not provide a specific estimate for its deferred maintenance exposure, Tennessee is included as a case study because of its potential to inform future assessment efforts in other states.

Policies developed by states such as these to identify, quantify, and fund their deferred infrastructure maintenance needs are especially important today. As the White House and Congress shrink programs and funding benefiting all fifty states, the states will need to become more self-reliant in areas directly affected by infrastructure policies, including public health, education, transportation, and disaster prevention and mitigation. Allowing deferred infrastructure maintenance shortfalls to widen will only present challenges for the funding and delivery of critical public services across the board.

This report, the first in a series of three published concurrently, compares varying definitions of maintenance and deferred maintenance, policies enabling statewide assessment and reporting, and processes used to assess deferred maintenance needs. It also summarizes accumulated deferred maintenance needs and associated funding allocations, and reviews state strategies to address current gaps and prevent future backlogs. In the other two reports we present (a) toolkits for policymakers and advocates across the US who may wish to emulate the reforms adopted by the nine selected states; and (b) a review of deferred infrastructure maintenance disclosure—or lack thereof—in capital budgets and centralized capital improvement plans across all fifty states.

Definitions of Deferred Maintenance and Maintenance

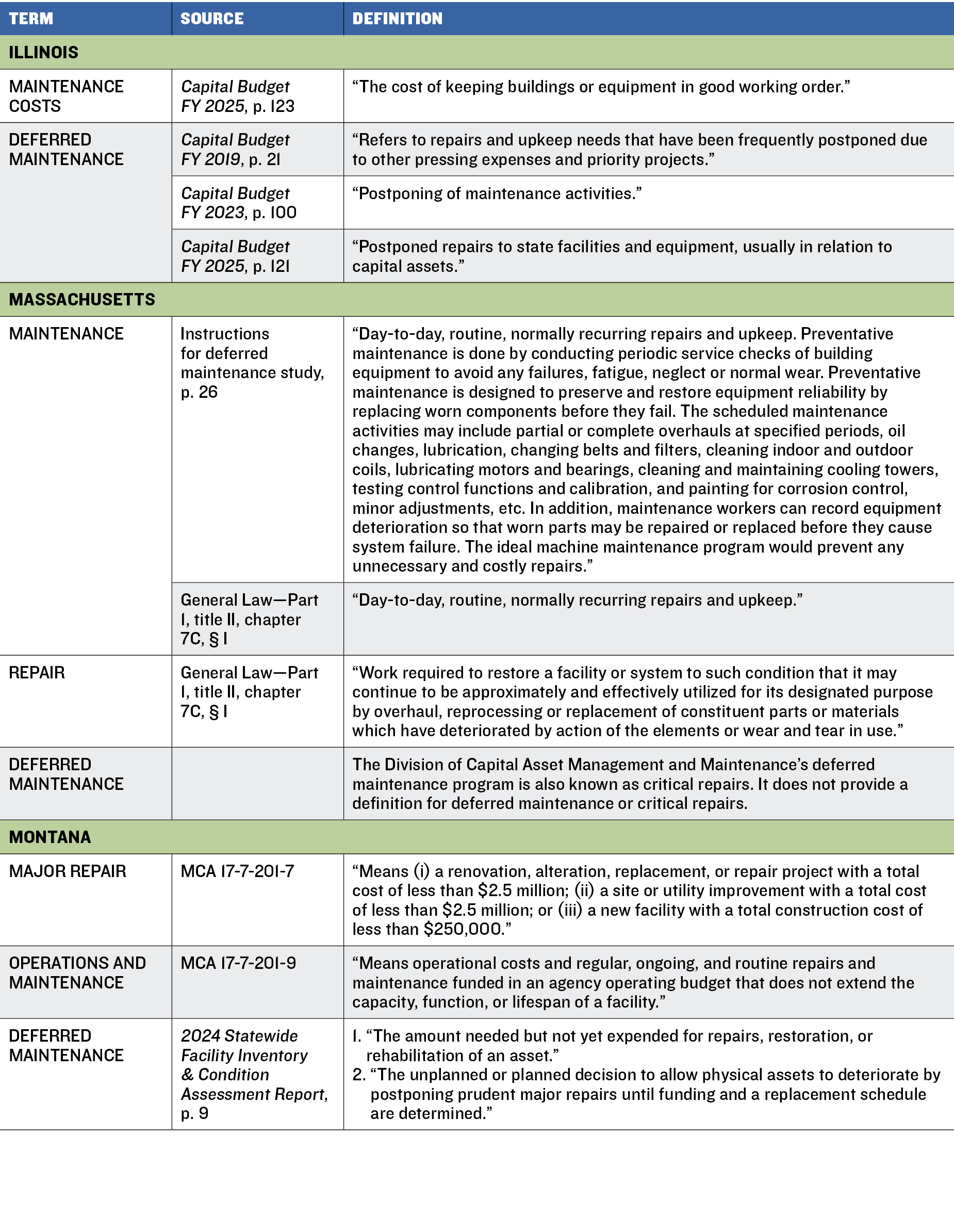

Most states analyzed use the terms deferred maintenance, deferred maintenance needs, deferred maintenance costs, deferred maintenance deficiencies, and deferred maintenance backlogs interchangeably, with a few referring to them as critical repairs. Three common elements emerge in the states’ definitions of deferred maintenance:

FRAMING THE DEFINITION. Deferred maintenance is generally described as maintenance that is postponed, delayed, or underperformed. The concept of maintenance in analyzed states often refers to repairs that are recurrent and scheduled to maintain, preserve, and extend the functionality of the infrastructure.

CLARIFYING THE POINT AT WHICH MAINTENANCE IS REGARDED AS DEFERRED. A certain amount of maintenance should be provided in a given period. Maintenance becomes deferred if not conducted by the end of this period. Only two states define this period explicitly: Hawaii, according to the repair and maintenance cycle; and Alaska, according to the budget cycle.

SPECIFYING THE SCOPE AND OWNERSHIP OF THE INFRASTRUCTURE. Hawaii and California specify the types (e.g., building, facility, or other improvement) and ownership (typically state-owned) of infrastructure covered in their deferred maintenance assessments.

Alaska, Idaho, Illinois, and Oklahoma also provide reasons for postponing maintenance activities in their definitions. The most common is insufficient funding, followed by perceived lower priority. Last, while definitions of maintenance are included in state statutes, definitions of deferred maintenance typically appear only in documents reporting on that topic.

Policy at the State Level Enabling Deferred Maintenance Assessment and Reporting

Statewide assessment of deferred maintenance requires policy direction from legislation or the governor to guide the process and delineate responsibilities of state agencies involved. These policies are important to align efforts from all state agencies and to ensure compliance. Of the ten states analyzed, Hawaii, Alaska, Idaho, Massachusetts, Montana, and Tennessee provide explicit guidance for assessing and reporting deferred maintenance or infrastructure needs. Pennsylvania refers to deferred maintenance in statutes, though public information on assessments, needs, and funding is limited. California, Illinois, and Oklahoma report deferred maintenance needs and allocate funding to them. California and Illinois lack a statewide policy, however, and Oklahoma only recently adopted one.

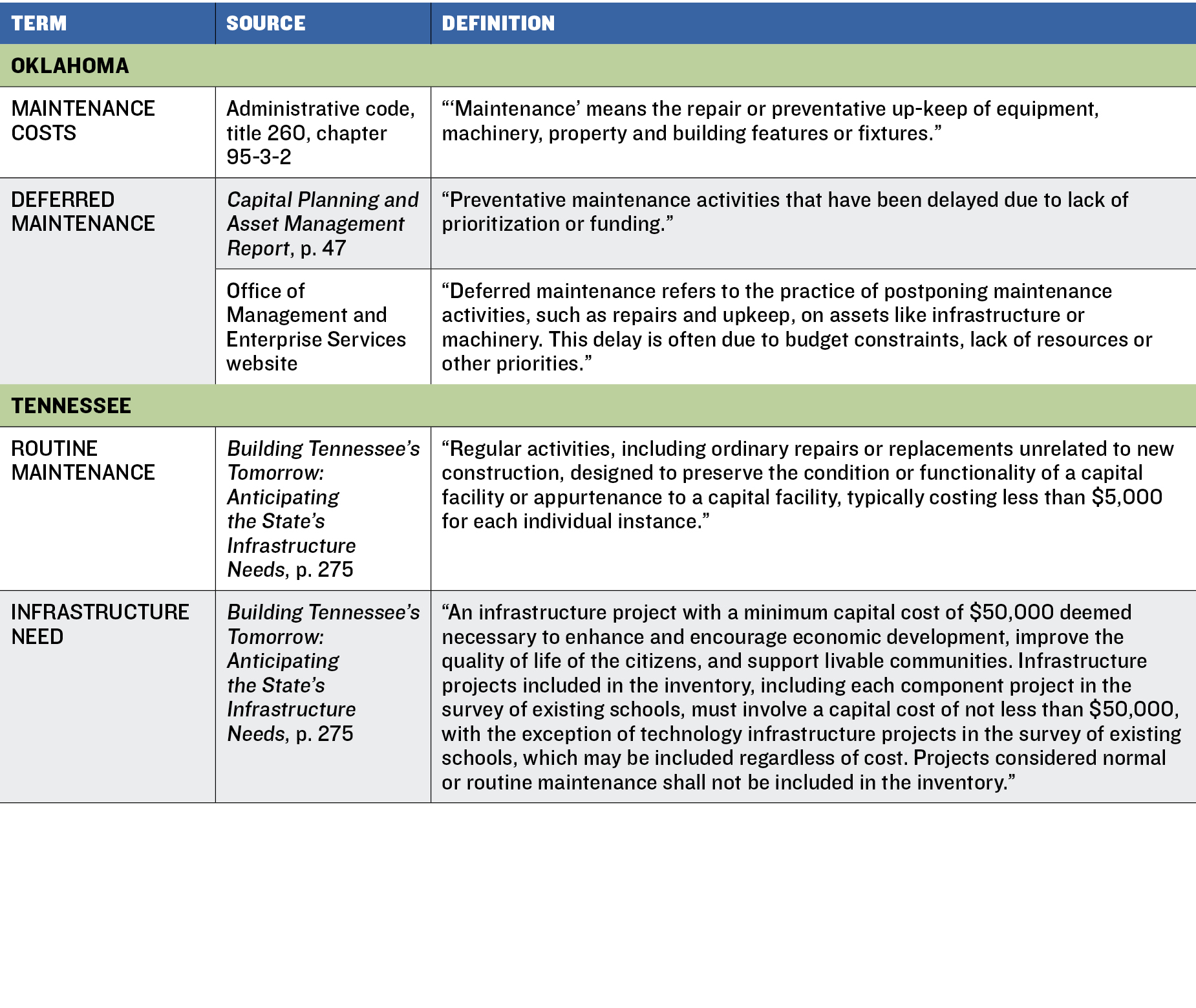

Policies typically designate a lead state agency—often the department or office in charge of budgeting and finance or administration—to collect, store, and report deferred maintenance information or infrastructure needs. Policies also determine the responsibility of other state agencies, either by requiring or encouraging them to provide information on deferred maintenance or infrastructure needs to lead agencies.

Policies in Hawaii, Alaska, and Idaho also require a plan to address deferred maintenance needs. The plans generally include an inventory or list identifying deferred maintenance pro-jects; a schedule for addressing deferred maintenance needs; criteria for prioritizing projects; and available funding sources to address deferred maintenance needs.

Assessing and Budgeting for Deferred Maintenance Needs

The process for assessing deferred maintenance needs and budgeting for them varies among analyzed states and depends largely on the types of infrastructure considered in the assessment. Most analyzed states limit assessment to buildings; California and Hawaii assess a broader range of infrastructure, including transportation assets. These considerations may be narrowed further by type of ownership (e.g., state, local); funding source (e.g., general and unrestricted funds), or cost thresholds (e.g., assets with certain replacement values).

Assessment processes also differ according to their scope. States assessing a broader range of infrastructure often use a decentralized approach, relying on separate state agencies to perform assessment tasks; those focused on buildings typically use a centralized approach and a designated lead state agency. The process is generally consistent across state agencies, including developing inventories; conducting facility condition assessments with regular physical inspections of the infrastructure to assess condition and identify deferred maintenance needs; and storing information in asset management systems for ongoing upkeep, monitoring, and sharing purposes.

Estimating Deferred Maintenance Needs

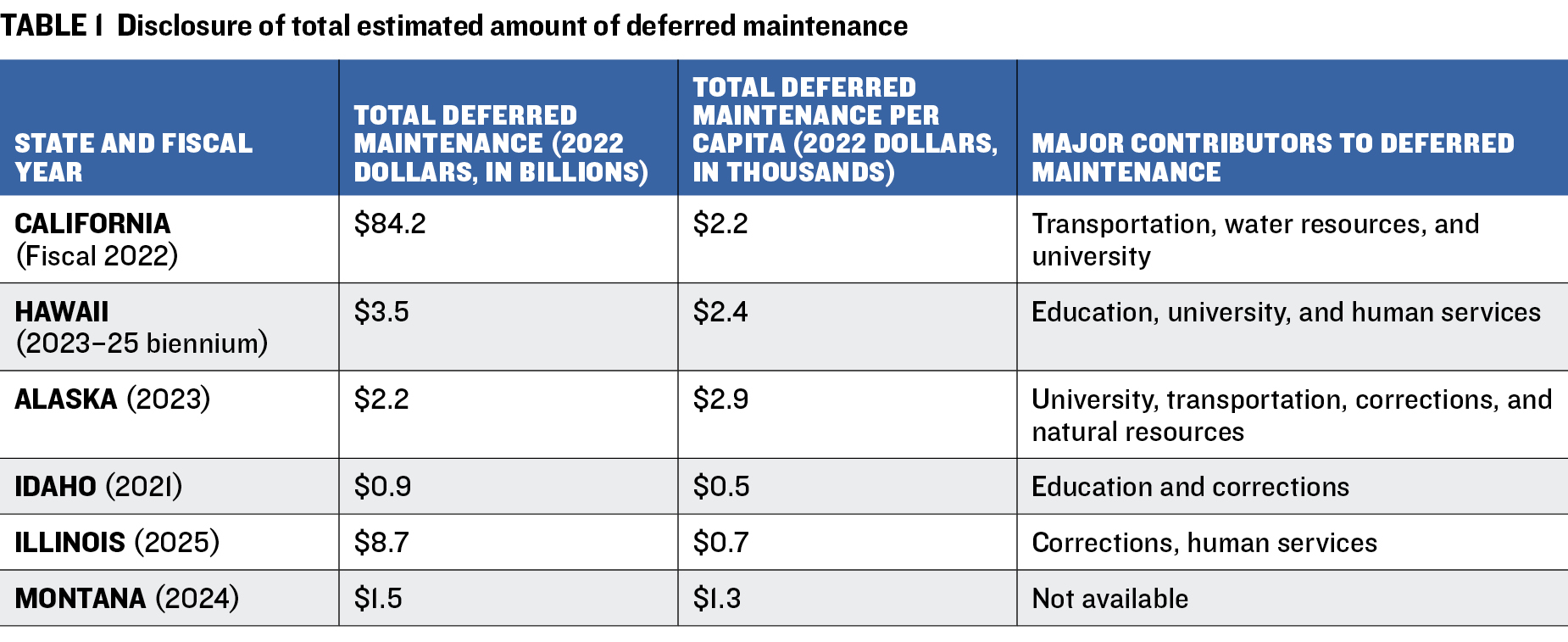

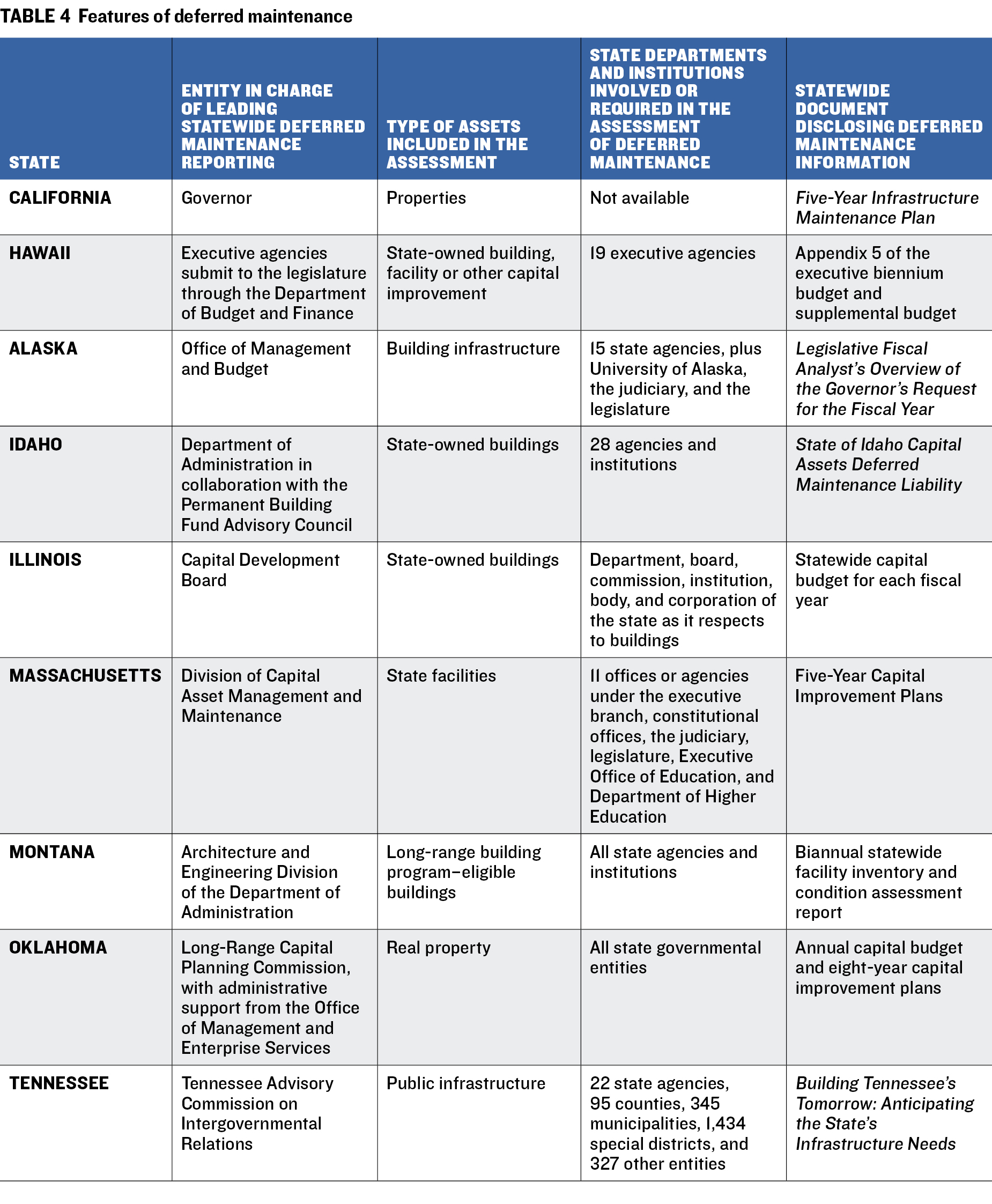

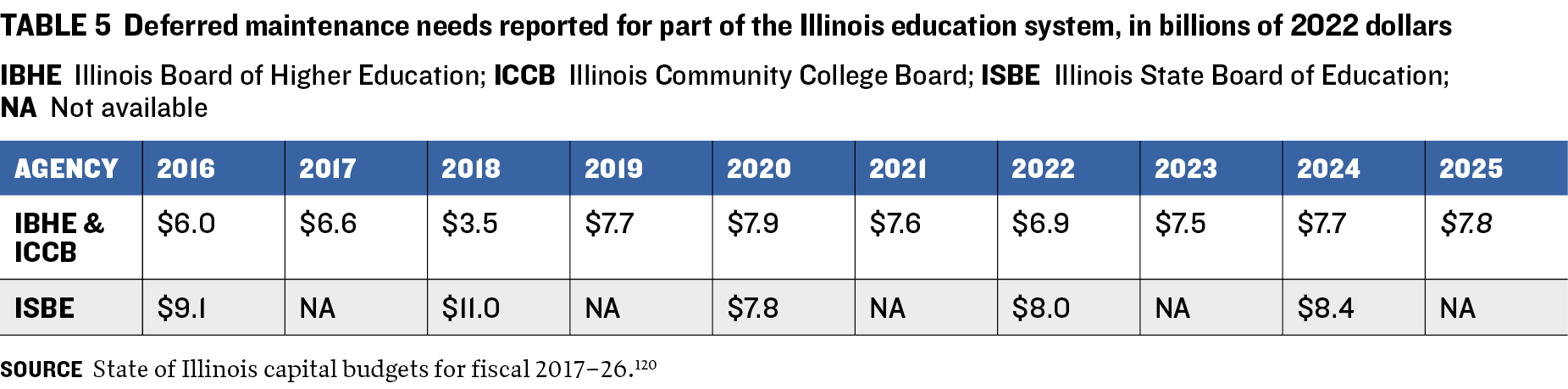

Comparing deferred maintenance needs in the analyzed states is challenging because of differences in the types of infrastructure included in their assessments. Of the nine analyzed states reporting deferred maintenance needs, only six disclose a total estimate amount for the assets they consider (see table 1). In these states, the largest contributors to deferred maintenance needs are the departments of education (including the school system and the college and university systems), corrections, and human services. Massachusetts and Oklahoma currently report only on the needs of education systems.

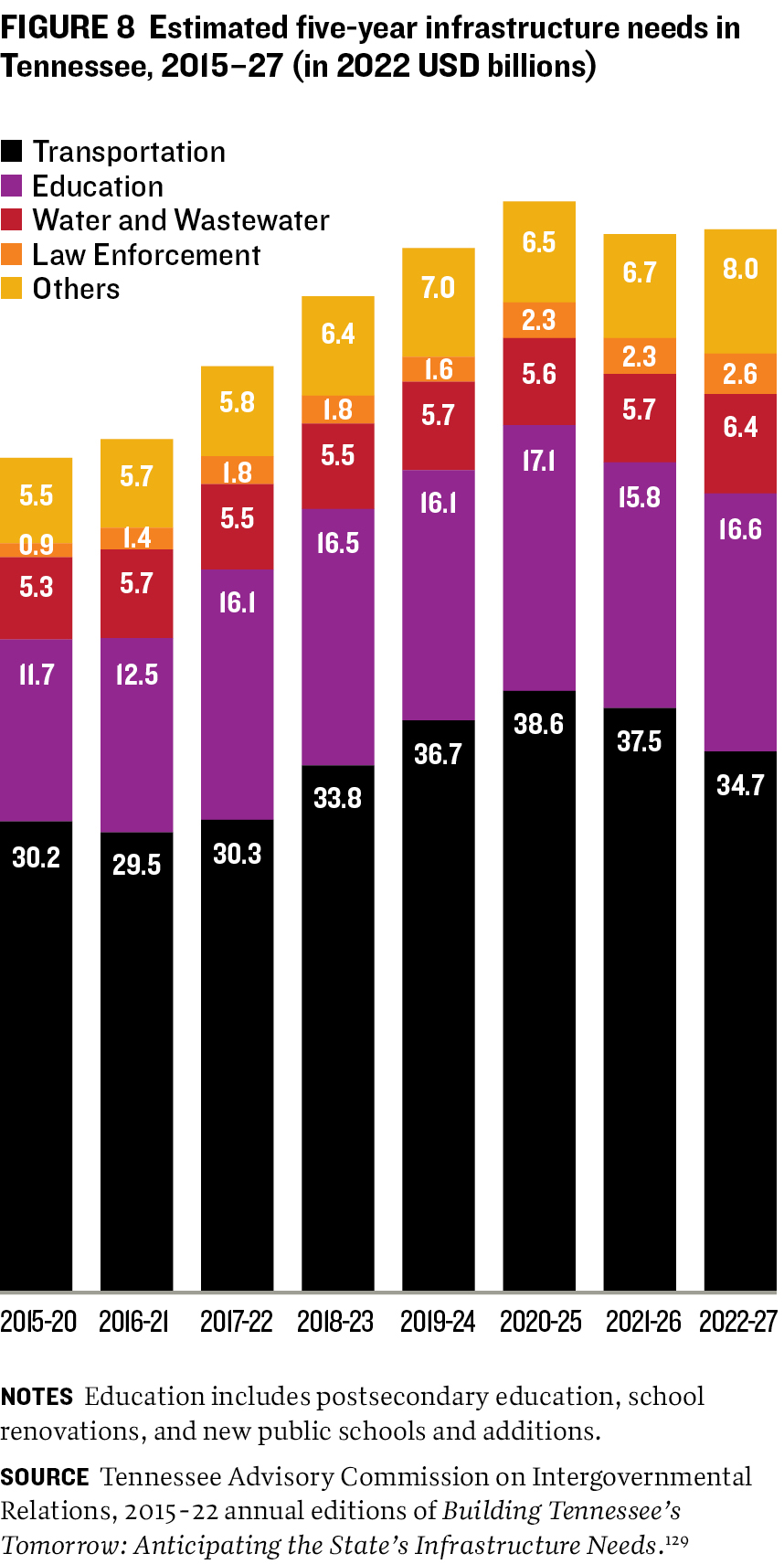

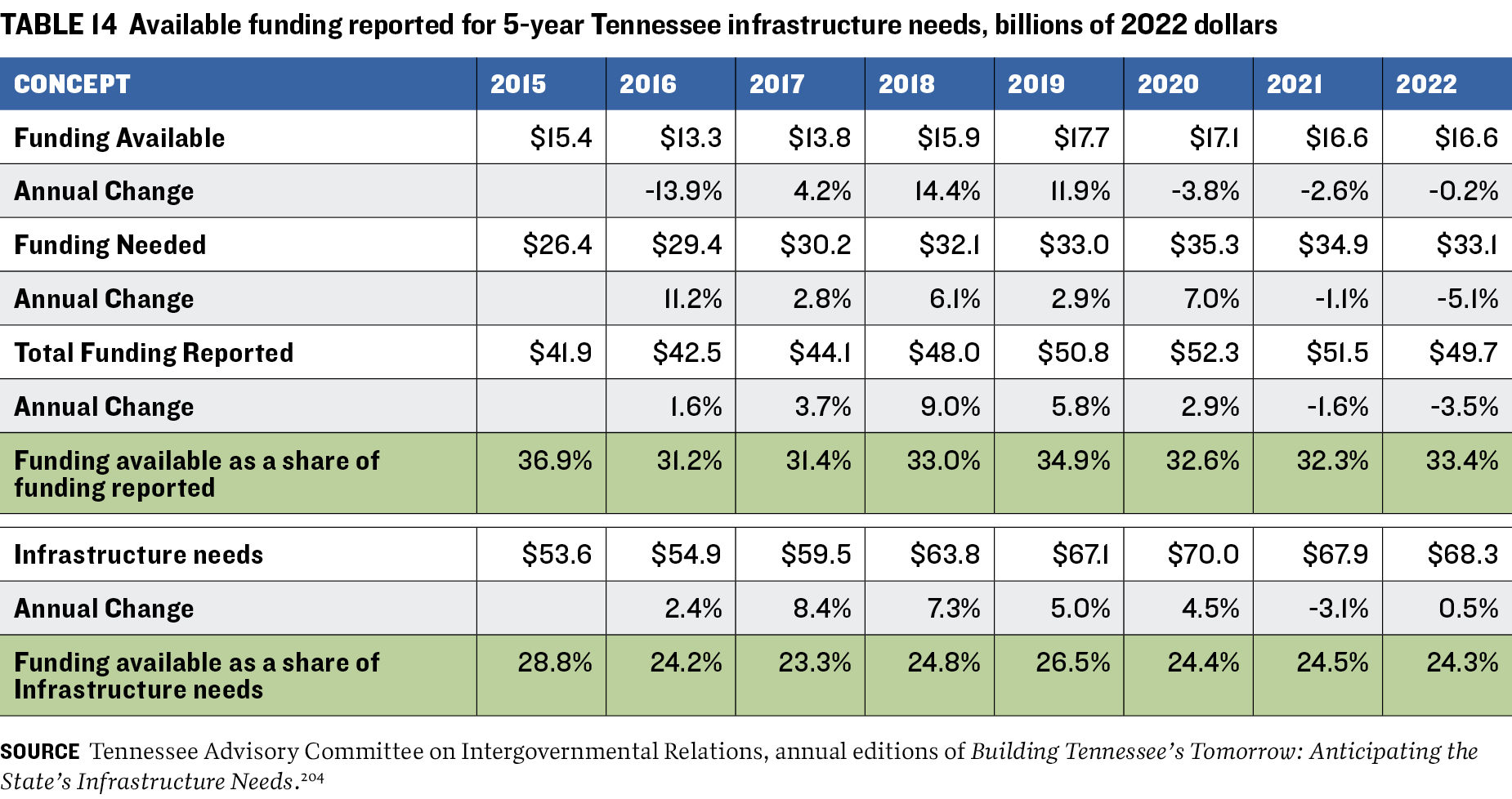

While not reporting deferred maintenance needs specifically, Tennessee estimates and reports its total infrastructure needs at $68.3 billion (in 2022 dollars) for 2022–27. Primary contributors include the state’s transportation, education, and water and wastewater departments.

Prioritization of Deferred Maintenance Projects

With limited funding to address pressing infrastructure needs, some analyzed states have developed processes to prioritize deferred maintenance needs. These processes vary in approach, methods, and metrics. California and Hawaii, which consider broad types of infrastructure, prioritize deferred maintenance projects primarily at the agency level. States focused on buildings, such as Alaska, Idaho, Massachusetts, Montana, and Oklahoma, take a two-step approach: Individual agencies submit their priorities, and the lead agencies prioritize projects according to statewide goals.

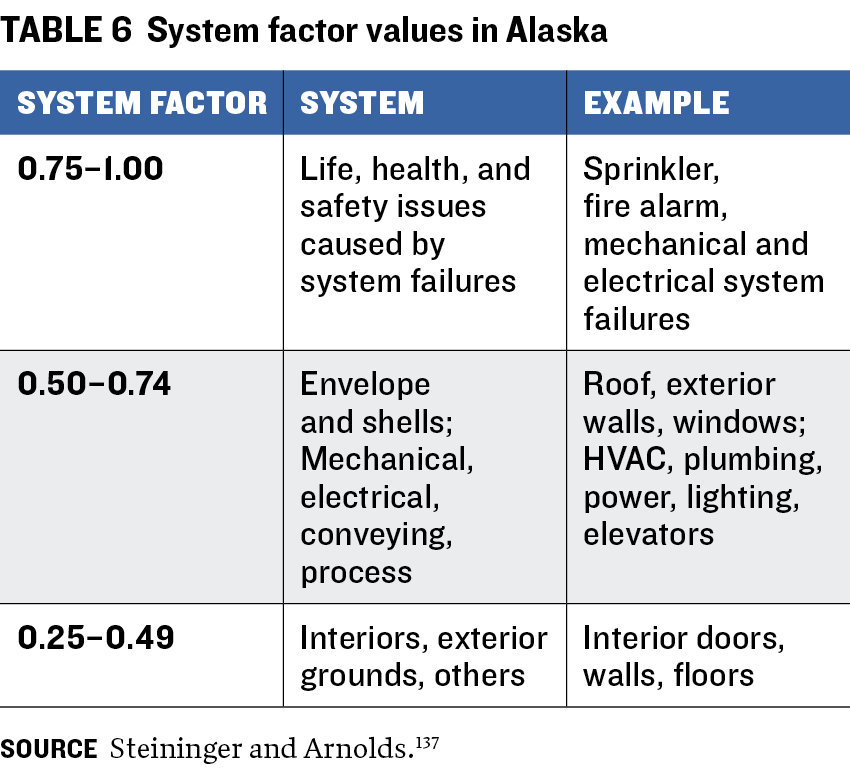

States also use different methods—from a data-driven approach that uses the facility condition index (FCI) as a metric, to a consensus-driven one that subjectively assesses a need’s criticality or urgency within the system with metrics such as the mission alignment index (MAI) and the system factor. They may also take a hybrid route that combines elements of various methods. Other metrics include funding leverage, legal obligation, mandates, and phases of the project already funded.

Funding Allocations for Addressing Deferred Maintenance Needs

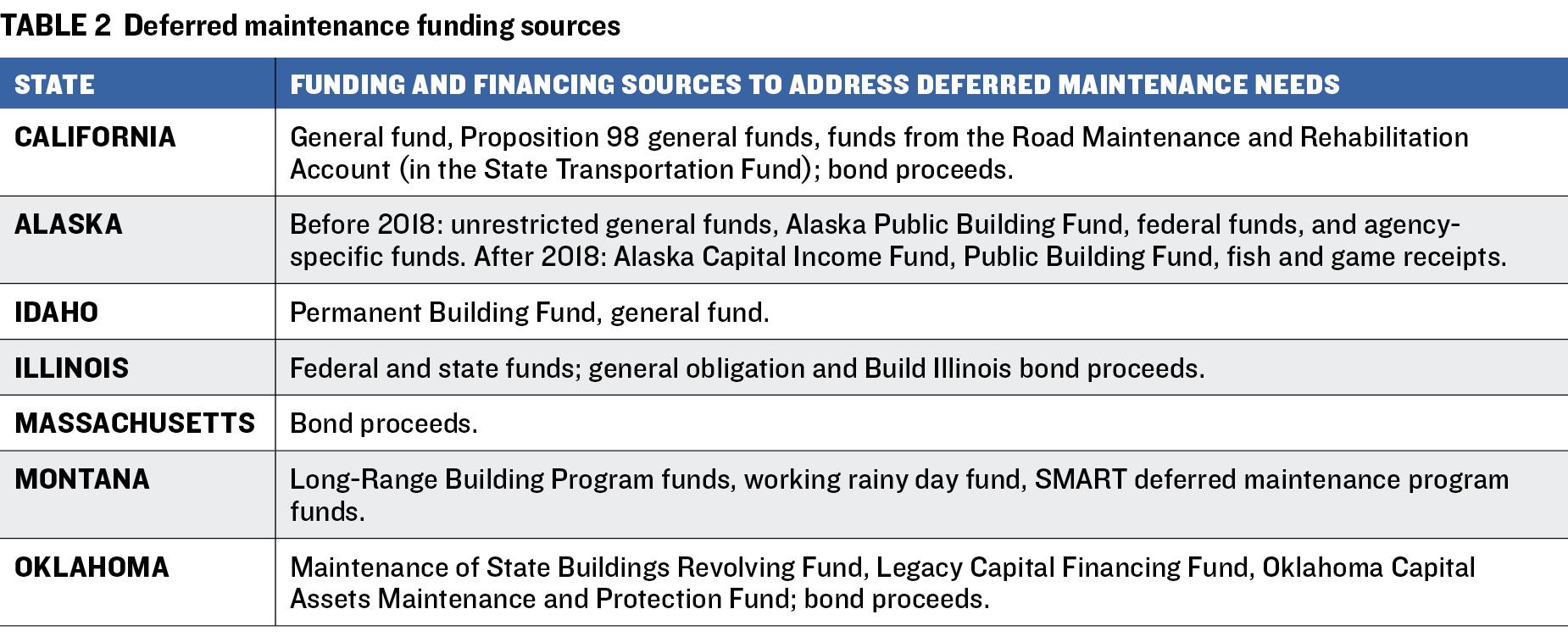

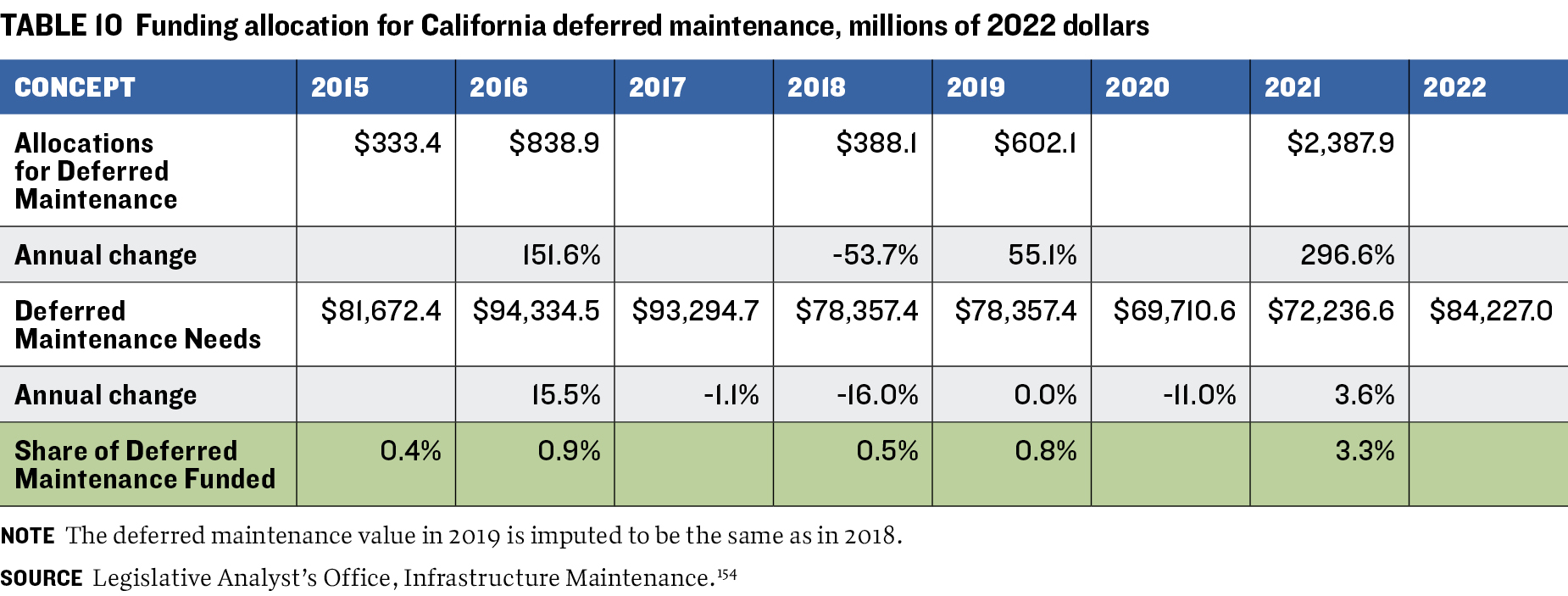

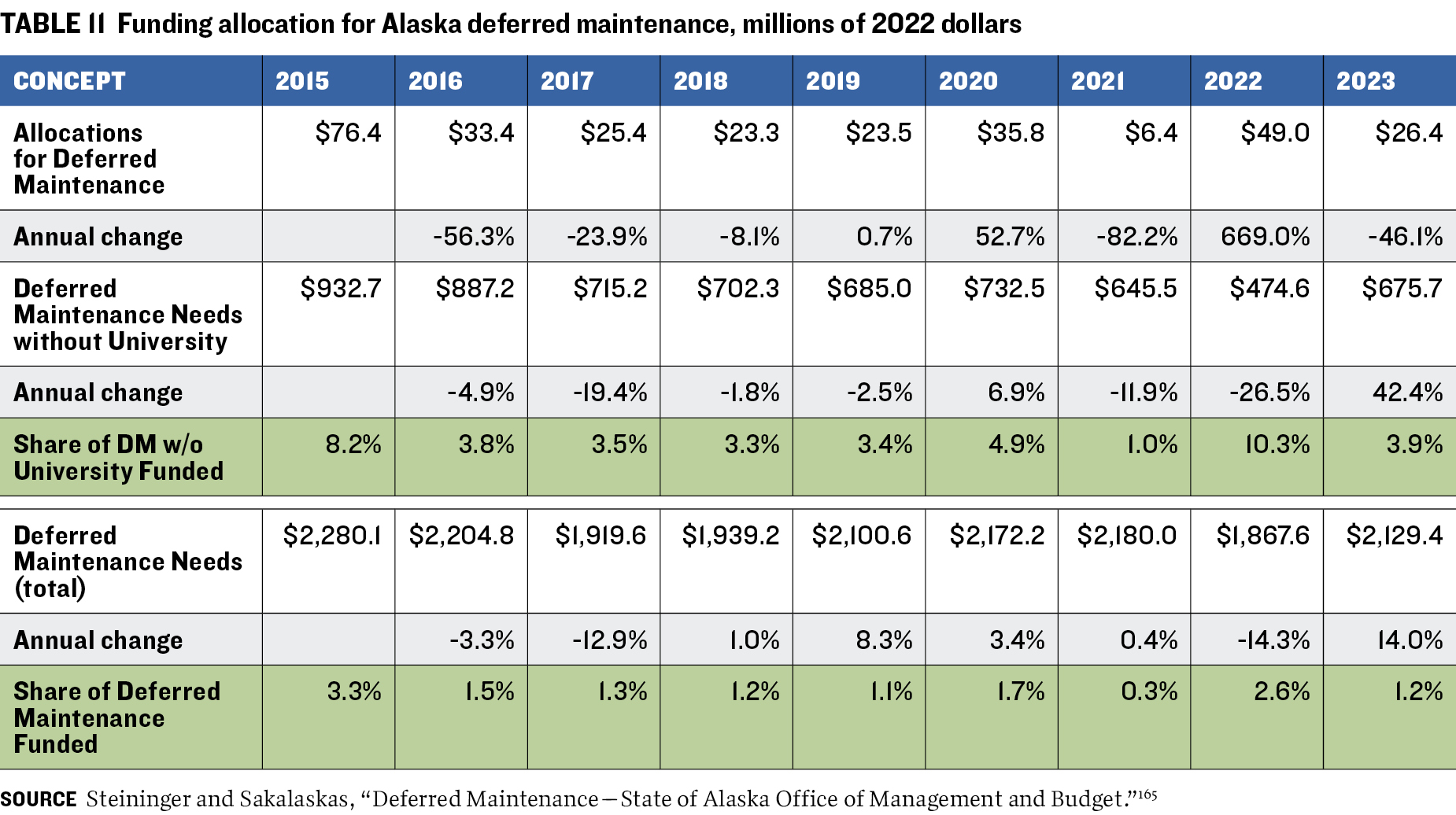

Seven analyzed states rely on a mix of funding sources to address deferred maintenance needs; the primary sources are general funds, followed by special funds (see table 2). A few states have also issued bonds to finance deferred maintenance. All analyzed states report the total amount of funding requested to address deferred maintenance needs in budget documents and line items of the amounts of funding appropriated to address these needs in appropriation bills. Only two states, California and Alaska, report both the total deferred maintenance backlog and the aggregated total amount of funding appropriated in a single report.

Funding appropriations in analyzed states typically cover less than 4 percent of identified deferred maintenance needs. For example, pre-2020 allocations in Alaska and California covered, on average, about 4.5 percent and 0.6 percent of needs, respectively.

Current and Future Plans for Addressing Deferred Maintenance

While all the analyzed states plan to continue their current efforts to address deferred maintenance backlogs, few have determined next steps or areas for improvement in their processes. Key strategies identified include:

EMPHASIZING EARLY INVESTMENTS IN PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE TO AVOID DEFERRED MAINTENANCE. In a slide deck prepared for a 2022 presentation to the Alaska House Finance Committee, state Office of Management and Budget Director Neil Steininger and Director of Facilities Services Melanie Arnolds said that while there is “no one definitive rule on the level of preventive maintenance necessary to avoid deferred maintenance,” they reported that a 2012 National Research Council publication cites “a range of 2-4 percent of replacement cost value.”2 Analyzed states that provide information invest less than this amount.

IMPLEMENTING TARGETED PLANS TO REDUCE EXISTING DEFERRED MAINTENANCE COSTS. Such plans focus on prioritizing and investing in deferred maintenance and often involve creating dedicated capital budget categories for deferred maintenance projects to distinguish them from other capital projects; and requiring state agencies to prioritize deferred maintenance and preventive maintenance over new capital projects (one state is considering establishing a facility condition index threshold for existing facilities for state agencies to meet before embarking on new capital projects).

They also include temporarily increasing or establishing a consistent funding stream that provides ongoing funding to address current backlogs.

INTRODUCTION

From the deteriorating Gowanus Expressway in Brooklyn, New York, to the aging dams that supply about 70 percent of California’s water, America’s public infrastructure is badly in need of rehabilitation.3 The nation is estimated to have accumulated about $1 trillion in deferred infrastructure maintenance4—broadly defined as recurrent and scheduled repairs that were postponed in favor of more pressing spending needs. Although such delays are viewed as saving money in the short run, they generally result in higher long-term maintenance expenditures and compromise public safety and health. And unlike financial liabilities such as bonded debt, pension obligations, and retiree health benefits, which state (and local) governments are required to disclose in standardized formats, deferred maintenance backlogs are rarely incorporated into capital budgets, annual comprehensive financial reports, or infrastructure needs assessments. This omission obscures the full scale of fiscal risk and hinders informed decision-making about infrastructure investment and public asset management.

Addressing this backlog is critical for the health of America’s $24 trillion economy.5 While Congress authorized $550 billion in new federal infrastructure outlays in 2021 as part of a broader post-COVID-19 economic recovery package,6 the primary responsibility for infrastructure investment continues to lie with state and local governments, which account for 79 percent of the nation’s public infrastructure.7 In light of constraints on federal funding and program support, state and local governments will continue playing a leading role in the upkeep and modernization of the infrastructure necessary to meet the evolving demands of the twenty-first century.

Recognition of the urgency around deferred maintenance is gradually spreading across the country. Nine states—Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Montana, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania—have made a constructive start on easing the trillion-dollar infrastructure crisis by implementing statewide efforts to assess and address deferred maintenance. In addition, Tennessee has for almost three decades provided an example for other states by conducting periodic statewide inventories of infrastructure needs, a critical first step for valuing and funding capital investment backlogs.

In this working paper, we examine the assessing, valuing, funding, and reporting of deferred maintenance in these ten states. Our discussion includes an explanation of the difference between ongoing and deferred maintenance, policies enabling statewide assessment and reporting, and processes used to assess deferred maintenance needs. We also provide updated summaries of the analyzed states’ accumulated deferred maintenance needs and associated funding allocations, including a review of their strategies to address current gaps and prevent future backlogs. Accompanying this study, we offer (a) a tool kit for governors, budget directors, legislators, and other stakeholders who may wish to address deferred maintenance gaps in their own states; and (b) a review of deferred infrastructure maintenance disclosure—or lack thereof—in capital budgets and centralized capital improvement plans across all states.

METHODOLOGY

This study involves a qualitative research approach. The research team conducted case studies on ten geographically diverse states to understand the policies, processes, and plans to assess and address deferred maintenance needs. Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Montana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee were selected for in-depth analysis because they already conduct statewide efforts to assess and address their deferred maintenance needs or produce statewide infrastructure inventories that could contribute to the assessment of deferred maintenance as identified in America’s Trillion-Dollar Repair Bill: Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs.8 This is not a representative sample, as states were chosen based on their leadership in this area.

Researchers studied key data points to understand how deferred maintenance needs are assessed and addressed: policies that enable statewide deferred maintenance assessment and reporting; definitions of current and deferred maintenance; processes to assess deferred maintenance needs, including agencies leading the efforts; state agencies involved in the assessment process or from which information on deferred maintenance needs are required; the type of assets included in the assessment; and the planning and budgeting for deferred maintenance needs. As part of the review, researchers also examined accumulated deferred maintenance needs and funding allocations to address them. Last, they looked at strategies that states undertook or considered for implementation to address current and prevent future deferred maintenance needs.

The study involved two phases. In the first phase, the research team reviewed documents available online to gain an initial understanding of states’ policies and processes. They scrutinized policy documents such as executive orders, senate and house bills, statutes; budgetary guidelines and directives; budget handbooks and instruction letters; and documents such as executive, capital, and operating budgets; and longer-term plans such as capital improvement plans (CIPs) and infrastructure plans. Statewide reports about deferred maintenance were also reviewed.

In the second phase, the team conducted interviews with state officials involved in the deferred maintenance assessment process. They included budget directors, directors of a fiscal division, budget analysts, financial administrators, research directors, research analysts, and legislative budget analysts in California, Hawaii, Idaho, Massachusetts, Montana, and Tennessee. Researchers interviewed seventeen state officials in seven individual and group sessions. Interviews were conducted from May 2024 to February 2025. State officials from Alaska did not participate in interviews but provided responses to inquiries via email. Analyses of states where interviews were not conducted were based on reviews of official documents.

In this paper, the researchers present findings about states ordered by the type of infrastructure considered in the deferred maintenance assessment. They first discuss findings from states that consider a comprehensive list of assets (California and Hawaii), followed by those that focus on a subset, such as buildings (Alaska, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Montana, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania). Findings from Tennessee are presented at the end, as they focus broadly on infrastructure needs, extending beyond deferred maintenance.

FINDINGS

Definitions of Maintenance and Deferred Maintenance

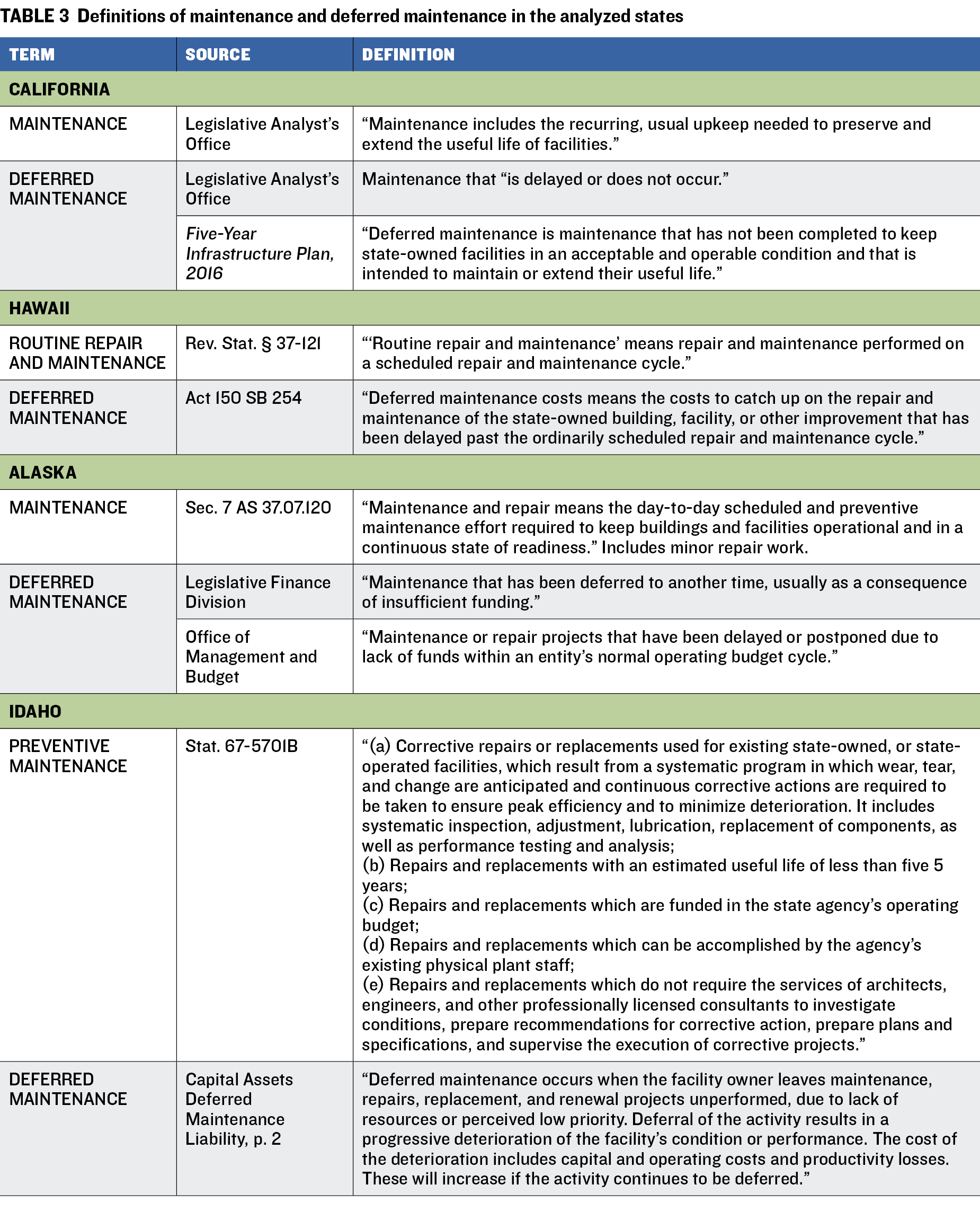

Defining “maintenance” and “deferred maintenance” is crucial to provide clarity and avoid misunderstanding among stakeholders involved in assessing deferred maintenance needs. Table 3 presents the definitions used in the analyzed states. It is worth noting that most states use the terms deferred maintenance, deferred maintenance needs, deferred maintenance costs, deferred maintenance deficiencies, and deferred maintenance backlog interchangeably. A few states refer to deferred maintenance as critical repairs. For purposes of uniformity, we use the term “deferred maintenance needs” throughout the analysis in this report; only when discussing specific aspects do we adopt the state’s terminology.

The definitions of deferred maintenance used by the analyzed states have three common elements:

FRAMING THE DEFINITION. All states refer to deferred maintenance as maintenance that is postponed, delayed, or underperformed. This requires reviewing the definition of maintenance to have a better understanding of the concept. Among analyzed states, the concept of maintenance generally refers to infrastructure repairs that are recurrent and scheduled to maintain, preserve, and extend its functionality. Alaska highlights efforts to keep infrastructure “operational and in a continuous state of readiness,” while California stresses efforts to keep infrastructure “in an acceptable and operable condition.” Hawaii is particular in defining deferred maintenance as the cost of catching up with maintenance that was delayed, which acknowledges additional costs incurred for not performing it on time.

CLARIFYING THE PERIOD IN WHICH MAINTENANCE BECOMES DEFERRED. A certain amount of maintenance should be provided within a given period, and maintenance becomes deferred if not completed in that time frame. Two of the ten states specify such a period. In Hawaii, it is the repair and maintenance cycle; in Alaska, it is the state’s annual operating budget cycle.

SPECIFYING THE TYPES OF INFRASTRUCTURE CONSIDERED AND THEIR OWNERSHIP. Two states refer to the type of infrastructure in their definition of deferred maintenance. Hawaii cites “state-owned building, facility, or other improvement,” while California pinpoints “state-owned facilities.” Both specify the state as the owner of the infrastructure. California Senate Bill 1, enacted in 2017, provides deferred maintenance guidance for state and local highways, roads, and streets, including the types of infrastructure considered. In their definitions, four states—Alaska, Idaho, Illinois, and Oklahoma—provide reasons for postponing maintenance.

These include insufficient funding (Alaska, Idaho, and Oklahoma), or perceived low priority (Idaho, Illinois, and Oklahoma). Although reasons for postponing maintenance are not included in its definition of deferred maintenance, California’s infrastructure plan and Legislative Analyst’s Office reports also refer to such reasons. They include insufficient funding, diversion of funding to other operational purposes, and poor facility management practices.9

DEFINING DEFERRED MAINTENANCE. While the definition of the word maintenance is generally included in state statutes, the definition of the term deferred maintenance is often included only in documents specific to the topic. Before adopting a definition of deferred maintenance, states often use a definition provided by another organization. In Alaska, for instance, the definition provided by the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board was recommended.10 Similarly, in Idaho, executive order No. 2021-10 required adoption of a statewide definition of deferred maintenance to quantify deficiencies. The definition was taken from a report issued by the National Association of State Facility Administrators.11

Policies at the State Level Enabling Deferred Maintenance Assessment and Reporting

Statewide assessment of deferred maintenance requires legislative or executive policies that provide guidance on the process and delineate responsibilities of state agencies. These policies are important to align efforts from all agencies and ensure that they comply with them. Among analyzed states, Hawaii, Alaska, Idaho, Massachusetts, and Montana provide explicit guidance for assessment and reporting of deferred maintenance, and Tennessee for infrastructure needs. Pennsylvania also refers to deferred maintenance in statutes but has limited public disclosure of assessments, accumulated needs, and funding. Oklahoma adopted policies that formally discuss deferred maintenance in 2024, but the state budgeted and funded deferred maintenance needs before that. By contrast, California and Illinois do not have a policy that explicitly requires deferred maintenance assessment or reporting. Both states report deferred maintenance needs and have funding appropriations to address them, however.

The analyzed policies typically designate a state agency to lead the collection and reporting of deferred maintenance information or infrastructure needs. The Department of Budget and Finance in Hawaii, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in Alaska, the Department of Administration (DOA) in Idaho, the Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance in Massachusetts, the Architecture and Engineering Division in Montana, and the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR) undertake these efforts.

Typically, other entities provide these agencies with data on deferred maintenance or infrastructure needs. Some policies require these entities to provide such information. In Hawaii, executive agencies responsible for operating or maintaining a state-owned building, facility, or other improvements must provide deferred maintenance estimates. Some policies encourage collaboration between entities. Idaho’s DOA works in partnership with the Permanent Building Fund Advisory Council and other necessary parties to develop a deferred maintenance report. And some policies authorize leading entities to request information but do not mandate that other entities submit it. In Tennessee, for instance, TACIR consults with state and local officials and can request infrastructure needs from state agencies.

In Hawaii and Alaska, the policies require a plan to address deferred maintenance needs. In Hawaii, the plan is required from the governor; in Alaska the OMB develops the plan, and the DOA administers it. In Idaho, the policy requires a series of steps to report on deferred maintenance needs, but these are similar to those identified in the other states. These plans have four common components. First, they all require an inventory of deferred maintenance projects (Tennessee’s infrastructure needs inventory provides a comprehensive example of efforts to consider and carry out.) Second, the plans of Idaho and Hawaii require identifying a timeline or schedule to address deferred maintenance needs. Third, the plans of Idaho and Alaska require criteria for project prioritization. Finally, the plans consider funding for deferred maintenance needs.

The following paragraphs provide details on the existing policies that enable deferred maintenance assessment and reporting for each state selected as a case study.

California

Although California does not have a statewide policy that explicitly requires deferred maintenance assessment or reporting, the state does report deferred maintenance in its infrastructure plan. The California Infrastructure Planning Act (CIPA) requires the governor to submit an updated five-year infrastructure plan to the legislature annually in conjunction with the governor’s budget. The plan must contain information concerning infrastructure needed by state agencies, schools, and postsecondary institutions; set out priorities for funding; and identify funding for the needed infrastructure.

The infrastructure plan provides information on statewide deferred maintenance needs in “Maintaining Existing Infrastructure.” The section offers a definition of deferred maintenance, reports the estimates of statewide deferred maintenance needs for the year, and identifies funding and financing opportunities. It also provides information on the governor’s proposed onetime resource allocation in the executive budget for addressing deferred maintenance needs each year.

In addition to the CIPA, Following passage of Senate Bill 1 (Chapter 5, Statutes of 2017), California established its Road Maintenance and Rehabilitation Program to address deferred maintenance on the state highway and local road system. It requires the California Transportation Commission to adopt performance criteria consistent with the asset management plan to ensure efficient use of resources and provides additional funding for deferred maintenance projects.

Hawaii

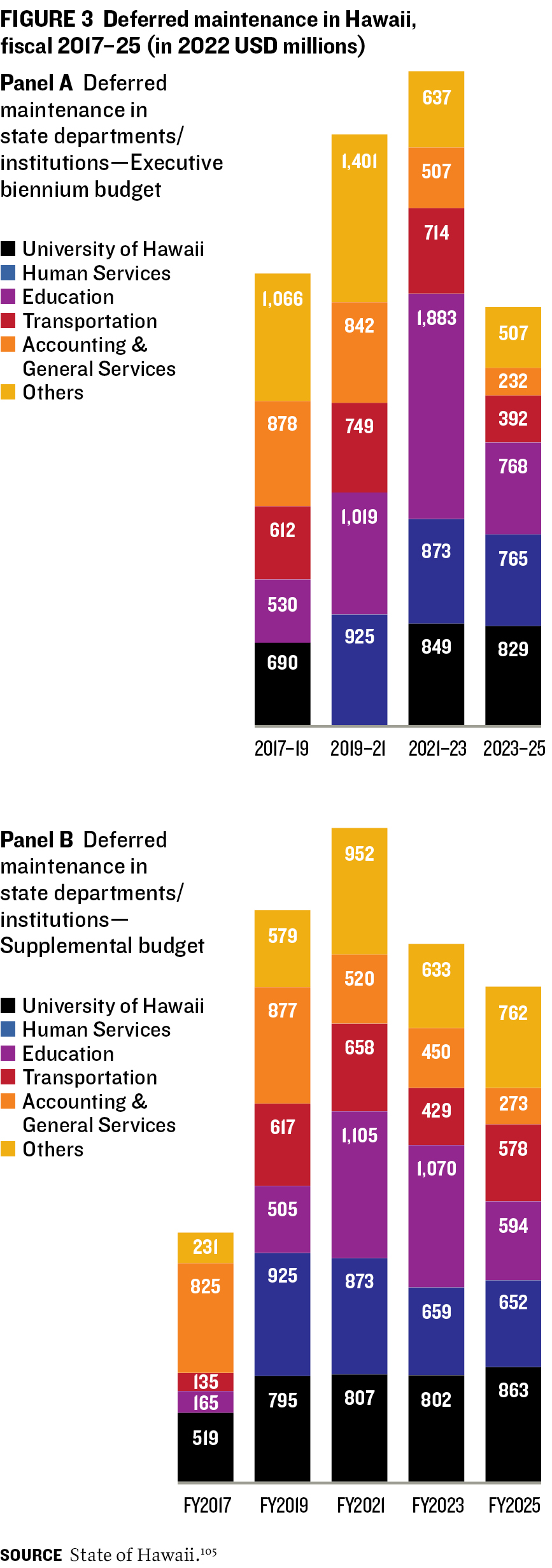

Act 150 (SB 254—June 26, 2015) requires that each executive agency responsible for operating or maintaining a state-owned building, facility, or other improvements provide the Department of Budget and Finance with an estimate of the deferred maintenance costs for the building, facility, or other improvements. The department is not required to ensure the accuracy of the information in the reports (Haw. Rev. Stat. § 37-122). The act also requires a summary of deferred maintenance costs collected by the director of finance to be included in the multiyear program, financial plan, executive budget documents, and supplemental budget. The multiyear program, financial plan, and executive budget are submitted to the legislature before the regular session in each odd-numbered year. The supplemental budget is submitted to the legislature before the regular session of each even-numbered year.

Senate Bill 719 (Jan. 20, 2017) found the extent of the state deferred maintenance backlog to be substantial and requires the governor to prepare a deferred maintenance plan12 to gradually eliminate the gap for state-owned buildings, facilities, and other improvements. According to the legislation, the act was found necessary to preserve facilities for public use or benefit, decrease future unfunded state obligations, preserve public resources by making maintenance investments instead of incurring expensive capital replacement or renewal costs, and promote transparency.

SB 719 provides the characteristics that should be included in the plan for it to be a guide for eliminating deferred maintenance costs. These include a target date and alternatives to the target date to address and eliminate the accumulated deferred maintenance costs; standards and criteria, as well as the designation of a state executive agency responsible for calculating deferred maintenance costs; an estimate of the total amount of funds necessary to eliminate deferred maintenance costs; and a proposed schedule and alternatives to the proposed schedule to eliminate deferred maintenance costs. The bill also requires the governor to update the plan annually.

Alaska

Although not enacted into law, House Bill 364 (July 1, 2002) proposed authorizing the Department of Administration to implement a plan developed by the Office of Management and Budget to undertake and finance deferred maintenance for state-owned capital facilities. The proposed plan would be required to identify capital projects to be addressed and their deferred maintenance costs, and prioritize projects based on available resources and emergent needs.

Idaho

Executive order no. 2021-10, “Transparency in Budgeting,” highlights the importance of estimating the cost of deferred infrastructure maintenance liabilities for state capital assets to further transparency in budgeting and ensure the state is properly investing in preventive maintenance.13 The order tasked the Department of Administration with developing a report on deferred maintenance liabilities in collaboration with the Permanent Building Fund Advisory Council14 and any other necessary parties. The order called for development of a consensus definition of the term “deferred maintenance” to improve measurement and enable better comparisons among state agencies and institutions; inventorying of the current cost of deferred infrastructure maintenance liability for the state’s capital assets by agency or institution, type of maintenance needed, and timeline necessary to address the maintenance; recommendation of best practices in funding deferred maintenance needs; and establishment of criteria for prioritization of project funding based on the criticality of the deferred maintenance.15

Illinois

Although the state does not have a statewide policy that explicitly requires deferred maintenance assessment or reporting, it does report deferred maintenance in the annual capital budget. The Governor’s Office of Management and Budget (GOMB) Act requires all state agencies to prepare and submit annual long-range capital expenditure plans (20 ILCS 3005/). These plans should include details of each project for the next three fiscal years, as well as project costs in current dollars, future maintenance costs, expected lifespan, and impacts on the agency’s annual operating budget.

According to the Illinois Capital Budget Act, the OMB is responsible for coordinating preparation of five-year capital improvement programs, which are updated annually, and yearly capital budgets in cooperation with all state agencies requesting a capital appropriation. The programs inventory the state’s capital assets; assess needs and resources; plan for capital investments and maintenance of existing facilities; and analyze the relationships between capital, maintenance, and operating spending. Each capital improvement program should include a needs assessment of the state’s capital facilities outlining the inventory; age; condition; use; sources of financing; past investment; maintenance history; trends in condition, financing, and investment; and projected dollar amount of need in the next five- and ten- year periods.

Massachusetts

The Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM)—created by the legislature in 1980 and within the Executive Office for Administration and Finance—is responsible for administering all capital planning, major public building construction, and facilities management activities for state-owned buildings (Office of the State Auditor, 2018). According to Chapter 7C, Section 2 of the General Laws, the commissioner of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance is required to carry out the systematic review of capital assets, scheduling of routine and scheduled maintenance repairs, tracking of deferred maintenance needs of capital assets, and coordinated planning of capital facilities in relation to the programmatic needs of state agencies.

According to Chapter 7C, Section 9 of the General Laws, the commissioner should prepare an analysis of the projected annual maintenance costs of each state building for which the final design was completed in the prior year. The projections are made over the useful life of buildings that are estimated to cost more than $5 million. In subsequent fiscal years, maintenance costs estimated in this analysis are to be included by the agency responsible for the operation and upkeep of the building in its annual budget request, along with revisions to the maintenance costs originally projected by the commissioner.

The commissioner is also responsible for preparing and revising a proposed capital repair and maintenance plan for state buildings subject to the jurisdiction of DCAMM. This five-year capital investment plan should include an analysis of costs and benefits of continuing minor repairs versus costs and benefits of major renovation, rehabilitation, or replacement of the state buildings. This report must be submitted each February to the House and Senate Ways and Means committees and the chairs of the joint committee on state administration and regulatory oversight.

Montana

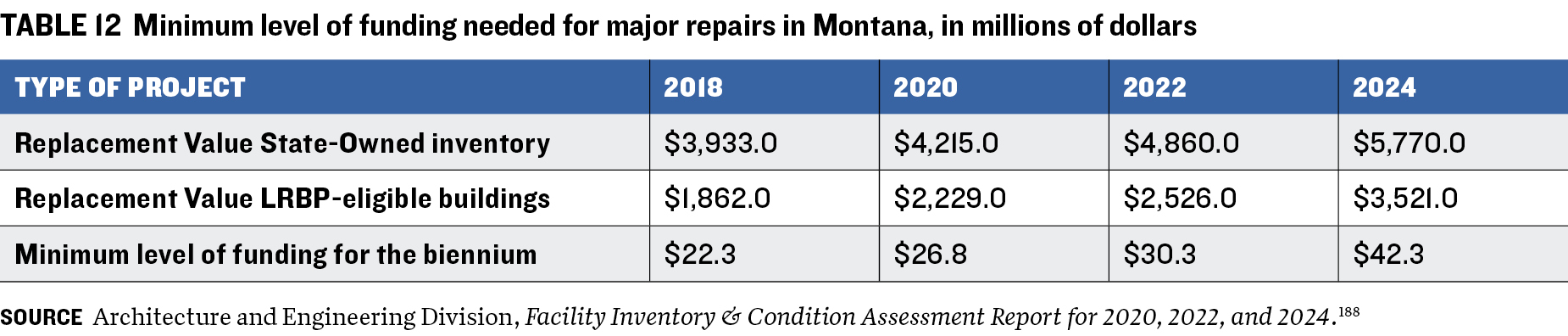

In 2017, the legislature passed Senate Bill 43 to reduce the increasing deferred maintenance backlog of state-owned buildings. The resulting law required the Department of Administration’s Architecture and Engineering (A&E) Division to establish a facility condition assessment (FCA) program to evaluate building conditions and to track and address the backlog over time.16 The bill amended two sections of the state’s annotated code, § 17-7-201 and § 17-7-202.

MCA § 17-7-202 provides that each state agency and institution shall submit a proposed long-range building program (LRBP) to A&E. The division must compile and maintain a statewide facility inventory and condition assessment that includes state-owned buildings and buildings eligible for an LRBP.

Among other provisions, for each state-owned building, A&E must identify the location and total square footage; identify the agency or agencies using or occupying the building; list the building’s current replacement value (CRV) in its entirety and for each agency’s portion of the building; and identify if the building is LRBP-eligible. A&E is not required to include a state-owned building with a CRV of $150,000 or less in the facility inventory and condition assessment.

For LRBP-eligible buildings, A&E must include an FCA and an itemized list of the building’s deficiencies and also compare its current deficiency ratio to that in the previous biennium.

For the statewide facility inventory and condition assessment, A&E may contract with a private vendor to collect, analyze, and compile the information required. The division is required to provide the facility inventory and the condition assessment, along with the calculation of the deferred maintenance backlog and overall building deficiency ratio of the building eligible for a long-range building program, to the Office of Budget and Program Planning and the legislative finance committee by Sept. 1 of the year preceding a legislative session.

Oklahoma

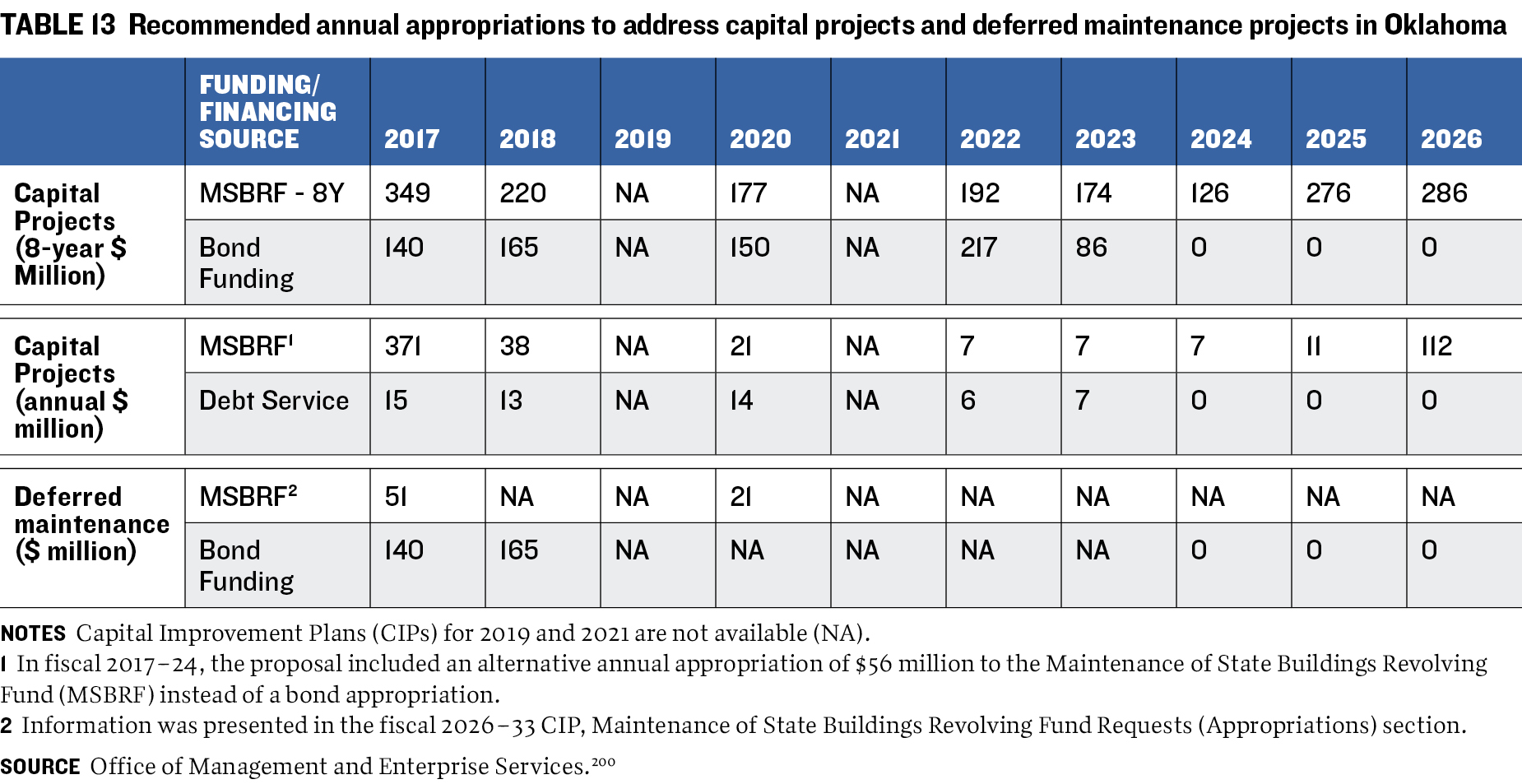

In 2012, Senate Bill 1052 recognized that steps must be taken to change the process of decision-making on capital facilities, which at the time was done individually by over 160 state agencies.17 In particular, the bill provided specific requirements for planning, budgeting, and developing an annual capital plan. Previously, the state had only a four-year capital improvement plan. The bill also required the Office of Management and Enterprise Services (OMES)18 to produce a report with recommendations for integrating and consolidating management of capital assets, including construction, maintenance, and real property management processes. In providing the recommendations, OMES suggested including deferred maintenance as part of capital budgeting.

The legislature finally passed the Oklahoma Capital Assets Maintenance and Protection Act in 2024 (Stat. § 73-188). The act authorized the Oklahoma Capitol Improvement Authority to provide funding for repairs, refurbishments, deferred maintenance, and improvements to property.

Pennsylvania

Title 8 § 1309 of the Consolidated Statutes of Pennsylvania indicates that the budget should provide for deferred maintenance. According to the statute, the budget must be as comprehensive and precise as available information will permit. In addition to expenditures proposed for the current fiscal year, the budget should also include a sum sufficient to cover any existing indebtedness and ordinary operating expenses for the subsequent year. It may also include funds to provide, in whole or in part, for any deferred maintenance, depreciation, and replacements.

Tennessee

In 1996, the Public Infrastructure Needs Inventory Act directed the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations19 (TACIR) to compile and maintain an inventory of infrastructure needs. (Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-10-109). The data from the inventory are deemed necessary to support efforts by state, county, and municipal governments in developing goals, strategies, and programs to provide adequate and essential public infrastructure.

The law also delineates information and processes, including definitions and types of public infrastructure facilities that, at a minimum, must be included in the inventory; data collection guidelines; stakeholders to consult in compiling the information; and presentation requirements. Among the law’s provisions are rules for:

ASSESSING PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE FACILITIES. These includes facilities that enhance and encourage economic development; improve the quality of life of residents; and support livable communities within each municipality, utility district, county, and development district region of the state. The inventory must also cover needs for transportation, water and wastewater, industrial sites, municipal solid waste, recreation, low- and moderate-income housing, telecommunications, public buildings (including city halls, courthouses, and K–12 educational facilities), and other public facility needs deemed necessary by TACIR. Infrastructure needs projects included in the inventory should not be considered routine maintenance and should involve a capital cost of at least $50,000.

FOLLOWING DATA COLLECTION GUIDELINES. The inventory must be taken using standard statewide procedures determined by TACIR to facilitate ease and accuracy in summarizing needs and costs. To complete the inventory, the commission can contract for services of the state’s nine development districts, an agency, or an entity of state or local government or higher education, and request needs from various state agencies. TACIR must collect and report on the infrastructure, urban services, and public facilities needs contained in the growth plans of cities and counties that have adopted such plans.

CONSULTING WITH STAKEHOLDERS. TACIR should consult with each county and local mayor, local planning commission, utility district, county road superintendent, and other appropriate local and state officials. Consultations concern planned or anticipated public infrastructure needs over the next five-year period, their estimated costs, and when the infrastructure would be needed within the time frame.

FOLLOWING PRESENTATION REQUIREMENTS. The public infrastructure needs inventory must be completed by agencies and submitted to TACIR each June 30. Information must be compiled by county and be presented to the General Assembly at its next regular annual session after completion of the inventory.

Assessing and Budgeting for Deferred Maintenance Needs

The process of assessing and budgeting for deferred maintenance needs varies in the analyzed states, largely according to the types of infrastructure considered in the assessment. California, Hawaii, and Tennessee consider a broad range of infrastructure types. In these states, individual state agencies are responsible for assessing their own deferred maintenance needs (or infrastructure needs in Tennessee) and submitting the information to a designated state agency that consolidates and reports the information. In contrast, Alaska, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Montana, and Oklahoma consider only buildings. In these states, a designated state agency is responsible for standardizing the assessment and consolidating the report of deferred maintenance needs.

Some states evaluate items such as ownership, source of funding, or cost restriction in the types of infrastructure they consider. In the first case, some limit the assessment to state-owned infrastructure (Hawaii, Idaho, and Montana). In the second, some limit it to infrastructure funded with state general funds (Montana). Finally, some limit the assessment to infrastructure with a certain value. For example, in Tennessee, included infrastructure must involve a capital cost of at least $50,000; and in Montana it must have a current replacement value of $150,000. Table 4 presents features of deferred maintenance in the analyzed states.

The process of assessing deferred maintenance needs is generally consistent across state agencies. It typically involves regular physical inspections of infrastructure assets to evaluate their condition and identify needs. Assessment information is then stored in software for ongoing upkeep, monitoring, and sharing purposes. In states focusing on building infrastructure, the lead agency often outsources the initial process to ensure that all buildings are assessed using the same standards, and individual agencies are responsible for regularly updating the assessment. In states that consider a broader range of infrastructure, individual state agencies take responsibility for the process. Some build in-house capacity to perform the assessment, while others contract it out. In most cases, individual state agencies are tasked with maintaining the assets.

The coverage of deferred maintenance in budget documents depends on the magnitude of the need. Smaller needs are usually included in the operating budget, while more costly ones are part of the capital budget.

The following section discusses in detail the assessment and reporting process for deferred maintenance needs used in each state that is a case study.

California

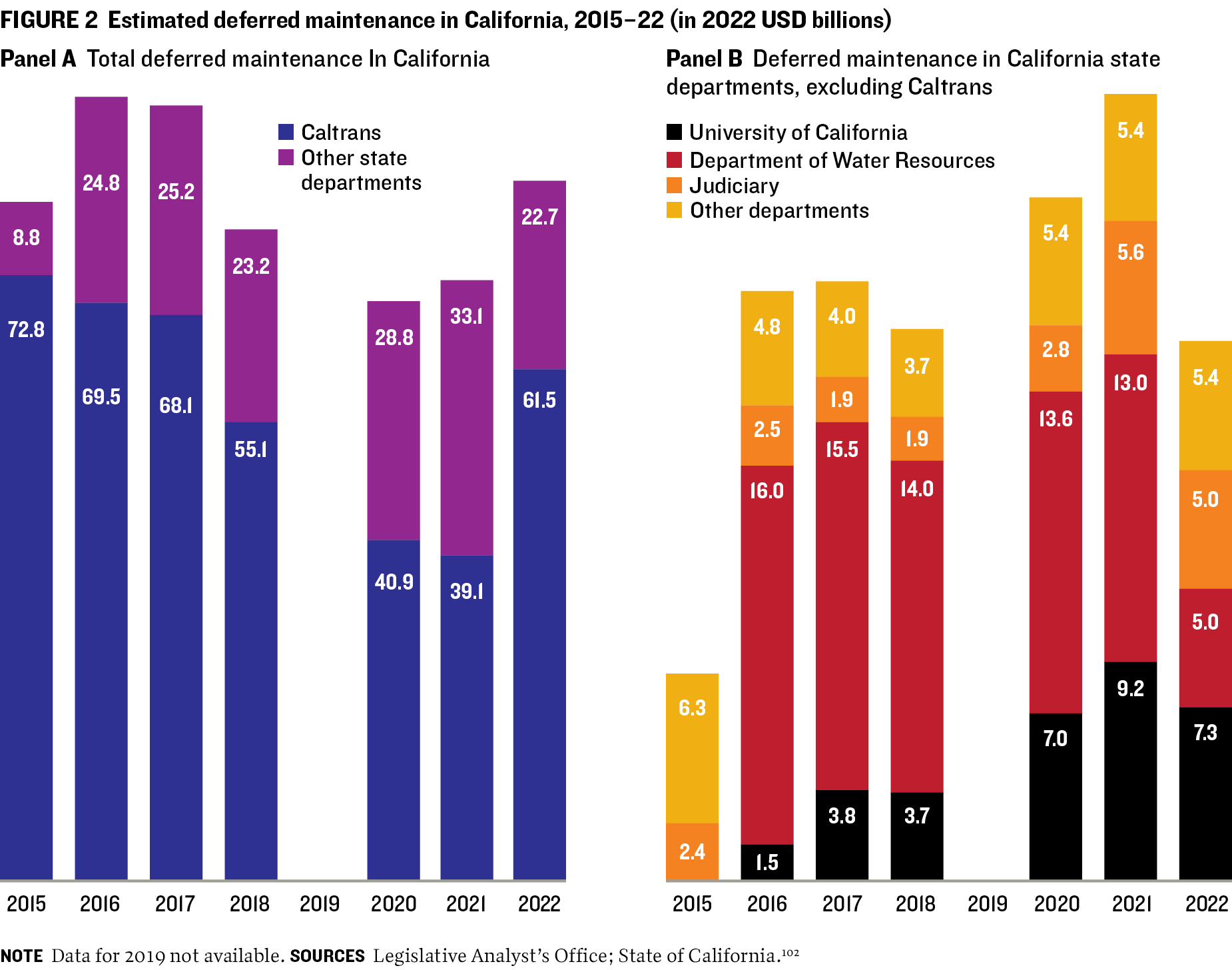

Though the state’s infrastructure plan began referring to deferred maintenance needs of the University of California (UC) system in 2008, it did not emphasize the statewide maintenance backlog until 2014. The infrastructure plan that year recognized the failure of previous ones to discuss the costs of upkeep for capital investments and of deferred maintenance. It aimed to correct those shortcomings and make the plan more relevant.20 Addressing the backlog of deferred maintenance was crucial to keep assets functioning longer and to reduce the need for expensive new infrastructure.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) viewed the governor’s initiative to address deferred maintenance as an important need but highlighted several issues that required legislative deliberation.21 In particular, the proposal lacked critical details about the projects, did not provide a clear methodology for establishing funding levels, and failed to address the underlying causes of the backlog. The office also found the process to identify deferred maintenance projects to be inadequate.

To address these concerns, the LAO issued a list of recommendations in 2016 concerning additional reporting required for deferred maintenance projects. These requirements include requiring each department to provide a list of proposed projects to be funded. The departments would also be obliged to detail in budget the causes of maintenance backlogs and their plan to address them. The LAO further recommended adjusting departmental funding levels based on legislative reviews of project lists, and requiring the projects approved by the legislature to be listed in the Supplemental Report.

The LAO gave the legislature additional recommendations in 2019, including requirements that departments receiving funding report at budget hearings their approaches to prioritize deferred maintenance projects, as well as specific projects they plan to undertake; that the Department of Finance report on which projects departments undertook with the funds provided (no later than Jan. 1, 2023); and that departments experiencing growth in deferred maintenance backlogs identify the reasons and the specific steps they intend to take to improve ongoing maintenance practices.22

Infrastructure considered in the assessment includes property, “including land and improvements to the land, structures and equipment integral to the operation of structures, easements, rights-of-way and other forms of interest in property, roadways, and water conveyances” (2009 Government Code § 13100–104).

Individual state agencies have their own approaches to identify deferred maintenance projects, prioritize them, and select them for the proposed funding.23 As such, the assessment and the methodologies used vary. For instance, UC uses its Integrated Capital Asset Management Program to identify, prioritize, and track deferred maintenance projects.24 Staff members physically inspect facilities to identify deferred maintenance and capital renewal and replacement projects. Infrastructure components inspected include roofs, building exteriors, elevators, heating and ventilation equipment and distribution systems, electrical and fire protection equipment, interior finishes, vertical and horizontal elements, site development, and utility systems. UC deferred maintenance projects cost more than $5,000; smaller projects are funded with regular maintenance funds.

Hawaii

The Department of Budget and Finance (DB&F) shares with other state agencies a memorandum containing policies and guidelines to prepare the Executive Budget Request for the biennium. This document also contains additional requirements for completing and submitting a deferred maintenance costs form with a cover letter. In reporting deferred maintenance costs, departments must provide information, including the organization code of the program that would be responsible for the cost, the location of the deferred maintenance (island), type of asset (building, facility, or improvement), description of the deferred maintenance, estimated amount, and any additional comments.25 The DB&F compiles information from state departments and prepares budget documents, including an appendix with estimated deferred maintenance cost information.

Infrastructure considered in the assessment includes assets such as a “state-owned building, facility, or other improvement” “owned by a state executive agency; provided that a building, facility, or other improvement shall not be deemed ‘owned’ by a state executive agency if leased by the agency to a person” (Senate Bill 719). In the 2023–25 biennium budget, all executive departments,26 including the University of Hawaii (UH), and the offices of the governor and lieutenant governor reported deferred maintenance information.

Hawaii Department of Education and the University of Hawaii

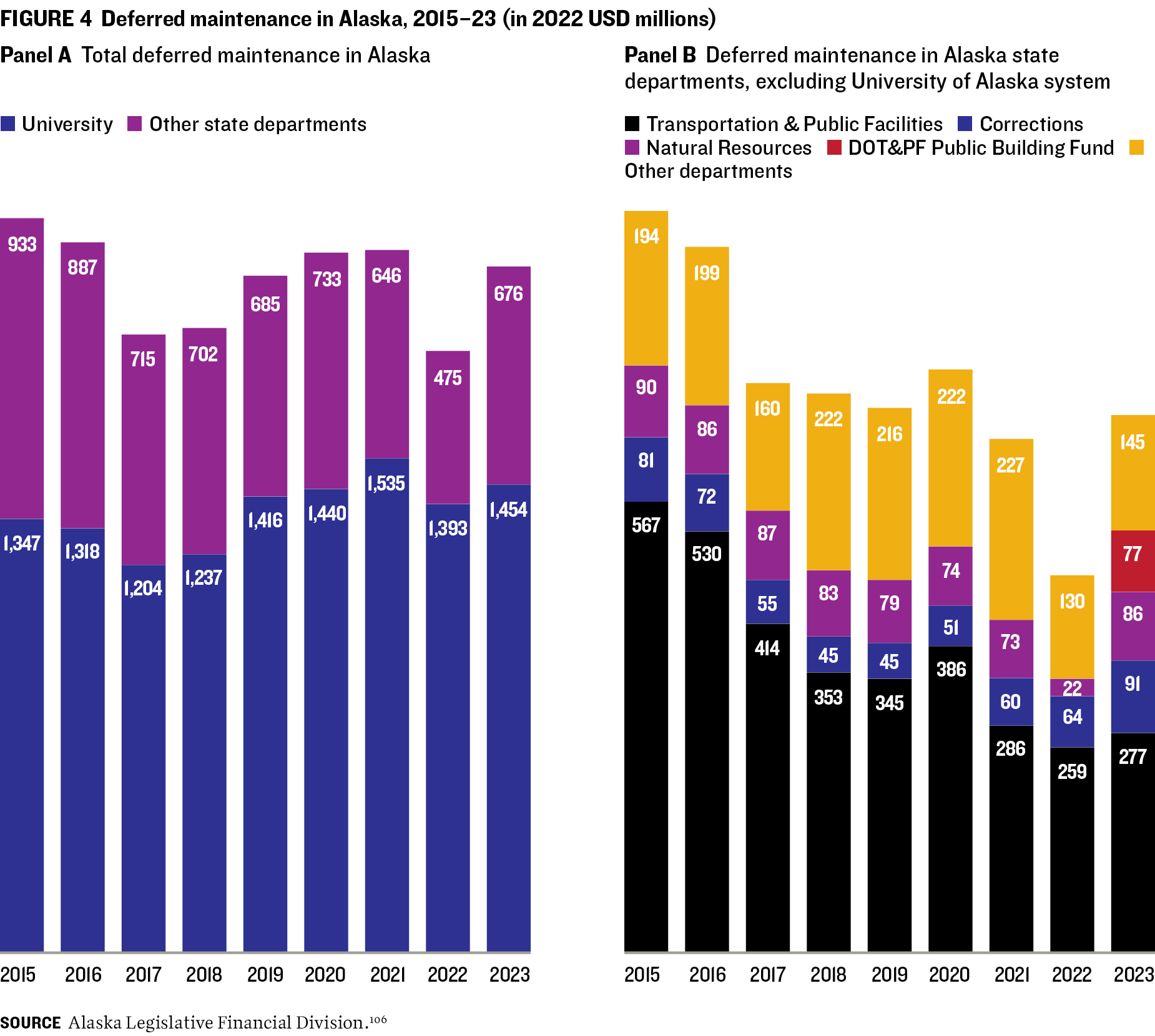

Alaska

The state started to centralize its deferred maintenance approach in 2015.30 At that time, most agencies managed the preventive and deferred maintenance of their facilities. This made the process of identifying the costs of deferred maintenance in Alaska very difficult. With the use of multiple and redundant systems, each with their own interfaces and capabilities, the Division of Facility Services (DFS)—part of the Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF)—recognized the need for a centralized system to provide a consistent framework for assessing and prioritizing deferred maintenance needs. The administration formed the Facilities Council in 2016 and in 2017 designated the DOT&PF the lead agency to consolidate statewide maintenance functions.31

Setting a statewide deferred maintenance system involved several steps:32 inspecting facilities to develop a facility condition index (FCI) with the aim to provide a holistic view of state building assets, setting a baseline condition of the assets, and analyzing deferred maintenance needs; developing a deferred maintenance framework to provide procedures and metrics to measure progress; and implementing a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) to provide long-term management, tracking, and reporting capabilities for all state-owned real estate.33 Implementation of the system began in early 2019 and all departments with facilities or leasing components are advised to use the system to assist with streamlining and automating processes.

The Alaska OMB currently facilitates the collection of all deferred maintenance needs across all state agencies. Once these are compiled into a list, it is sent to the Facilities Council, which reviews and prioritizes deferred maintenance projects in executive branch agencies (see prioritization process description in 3.4 ). Members of the council conduct several workshops in February and May to discuss all projects on the list. Once the review and prioritization processes are completed, the council approves a statewide prioritized list of deferred maintenance projects and provides it to the OMB in June.34 The office uses the list to inform recommended allocations for deferred maintenance needs.

The governor submits to the legislature an annual capital budget, which includes deferred maintenance appropriations. The Finance committees in both chambers review, vote on, and approve capital project submissions.35 Projects included in the budget are often large or of critical need. But deferred maintenance capital projects are occasionally funded through the operating budget, and Capital Improvement Project receipts are used to reflect those expenditures.

Infrastructure considered in the assessment includes buildings, including storage facilities.36 Deferred maintenance documents refer to state-owned facilities, which generally means properties and buildings owned, managed, or controlled by the state, including public buildings, transportation infrastructure, and other facilities used for state operations.37

Agencies involved in the deferred maintenance assessment, in addition to the University of Alaska, include the judiciary and the legislature. In all, fifteen state agencies may receive deferred maintenance funding and are required to report on the progress of their respective projects.38

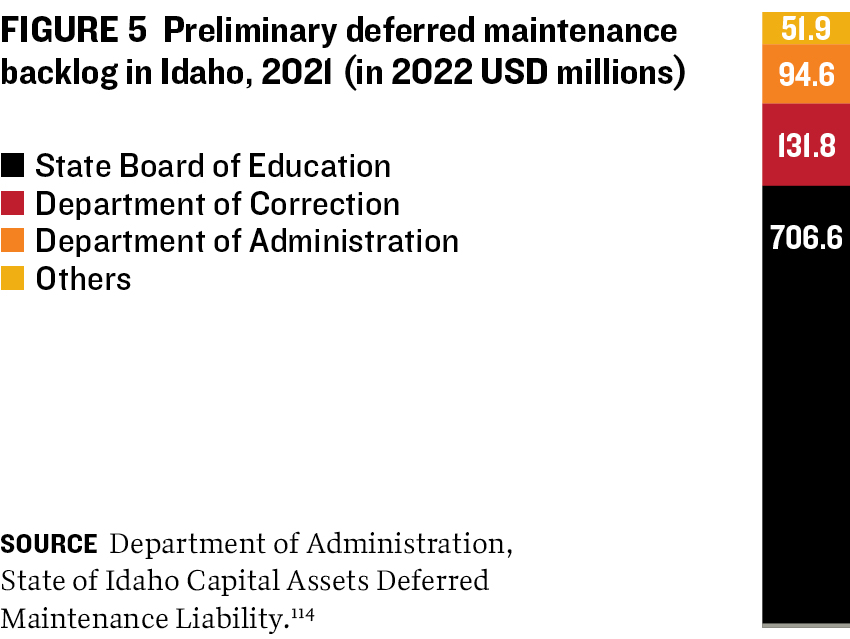

Idaho

The Department of Administration’s Division of Public Works (DPW) initially used capital budget information to assess deferred maintenance needs but realized that the reported information underestimated the state’s accumulated deferred maintenance.39 In particular, state agencies and institutions submit a section for alteration and repair projects as part of their annual capital budget request to the Permanent Building Fund Advisory Council (PBFAC). The section includes projects that are typically related to an agency’s deferred maintenance deficiencies. Agencies generally submit a few top-priority projects as the PBF has limited resources and cannot cover all requests.

Concerned with potential inaccuracies, the Department of Administration (DOA) implemented a vendor-sourced facility condition assessment system (FCAS) for deferred maintenance needs.40 According to PBFAC, having a single vendor handing the FCAS for all agencies ensures a consistent and comparable approach. The FCAS contributes to maintaining a comprehensive inventory of state capital assets (storing asset information such as location, size, acquisition date, replacement value, and the costs of maintenance deficiencies) and their deferred maintenance costs.

Executing the FCAS required contracting with Gordian to implement the assessments. This included on-site inspections to determine and document the condition of a facility and identify repair, rehabilitation, and replacement needs and costs; populating the FCA software;41 and calculating the facility condition index.42 The firm began working in July 2021 with FCAs at the Capitol Mall and Chinden Campus; it later started working with state agencies and institutions to perform the statewide FCA in June 2022 and was expected to assess about 30 million square feet across the state.

By May 2024, the firm had completed about 90 percent of the statewide assessment and was expected to have a complete assessment by December 2024.43 The data gathered during the assessment is organized in the software and is provided to each agency and institution as their portion of the assessment is completed. State agencies and institutions can use it to identify deferred maintenance and plan for maintenance replacements. Once the firm completes the assessment, each agency and institution will be responsible for updating their information and adding new facilities to the database.

Infrastructure considered in the assessment includes the so-called vertical portfolio of the state administered by the Division of Public Works, mostly office buildings.44 This includes building interior structures and systems as well as exterior features such as roofs, walls, and windows. For campus-type facilities such as a university, the division administers infrastructure including roads and water and sewer systems.

Idaho’s 2021 preliminary report on deferred maintenance includes estimates from twenty-eight of the state’s sixty agencies and institutions.45, 46 Idaho Statute 67-5711 exempts the DOA from the review of public buildings, except for administrative office buildings and associated improvements, under the jurisdiction and control of the Board of Regents of the University of Idaho, Idaho Transportation Department, Department of Fish and Game, Department of Parks and Recreation, Department of Lands, and Department of Water Resources and Water Resource Board.

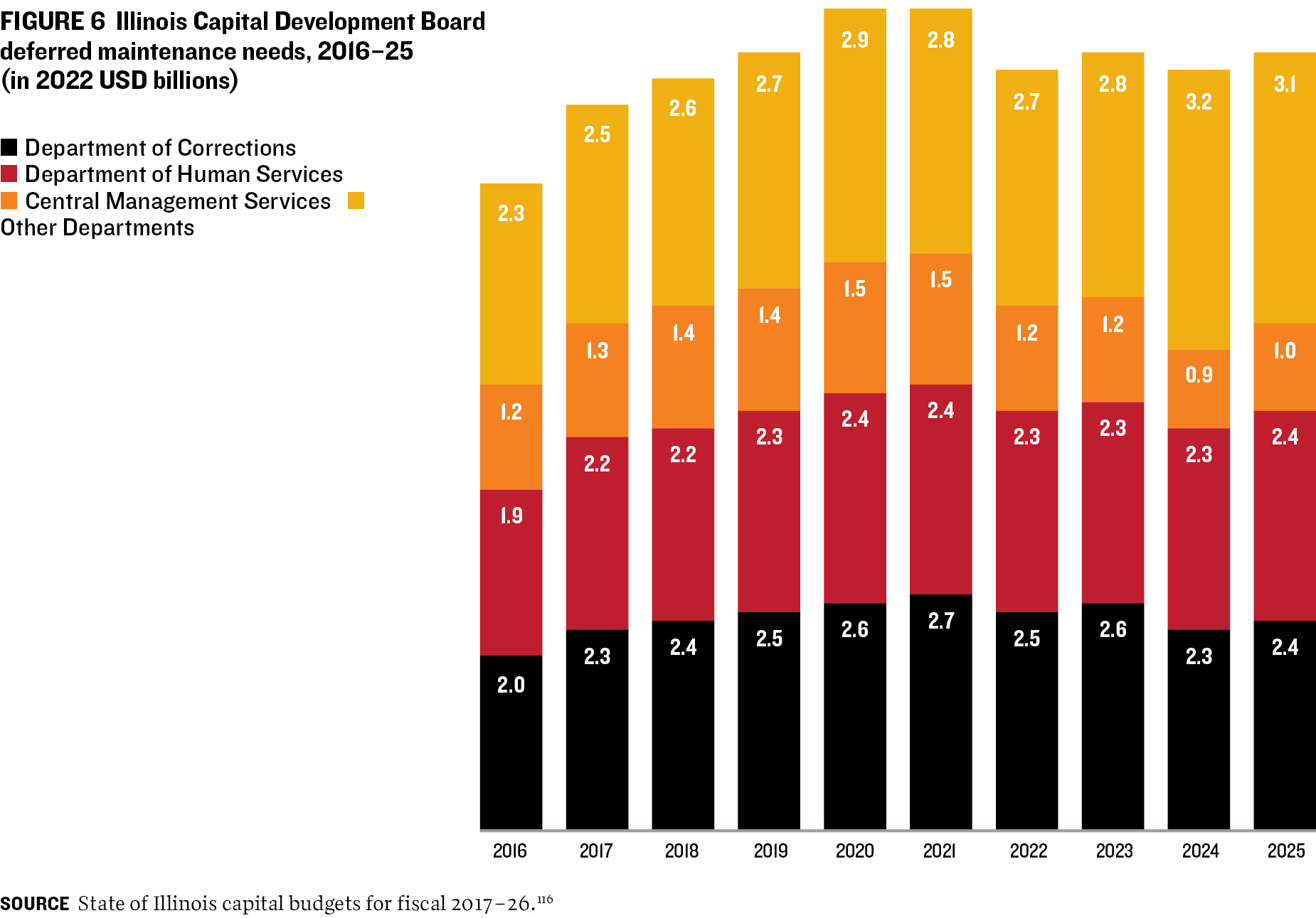

Illinois

The state Capital Development Board (CDB)47 reports deferred maintenance needs for state facilities. The CDB is the state’s vertical construction management agency and is responsible for overseeing the design, construction, renovation, and rehabilitation of state-owned buildings48 (20 ILCS 3105/). The CDB engages architects and engineers to perform high-level facility condition assessments for selected state-owned facilities and to identify state facilities as priority assets.49 The assessment includes inventory, visual inspections, quality assurance, and reporting; it involves teams that inspect facilities identified as priorities to evaluate the remaining life cycle of major asset systems, identify deferred maintenance requirements, and document deferred maintenance deficiencies. The inspection should include the architectural, mechanical, electrical systems, and other specific site systems provided by the CDB. The architects and engineers provide assessment data in an Excel file, with each building component assigned a condition, installation date, quantity, and replacement cost. In addition to condition assessments, architects and engineers provide inspection categories and a rating system to interpret assessment data. These data are used for calculating the building condition index, system condition index, and facility condition index ratings.

The CDB annually submits the list of projects to be included in the statewide capital budget. This budget includes deferred maintenance as one of the five major initiatives to address. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) works with state agencies—including the CDB—to review potential capital investments and projects. Other agencies with large capital programs include the Department of Transportation, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, and Department of Natural Resources. In developing the capital budget proposal, OMB considers the impact of deferred maintenance and whether investments would prevent the need for more expensive repairs in the future.51 Other considerations include whether the investments support the government’s strategic priorities, meet program needs, save future operating costs, and maximize use of available funds from federal, local, or private sources as well as bond offerings.

The governor annually submits the capital budget to the House and Appropriations Committees and the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability.

Infrastructure considered in the assessment for the CDB include office buildings, health care facilities, secured facilities, state fairgrounds, laboratories, correctional centers, residential care facilities, garages, state parks, and historic buildings.52

Every state agency in Illinois that proposes to adopt new building or construction requirements, or amendments to existing requirements, reports that proposal to the CDB (20 ILCS 3105/3 & 19b). For this purpose, state agencies include each department, board, commission, institution, body, and corporation. This does not include the Illinois Department of Transportation,53 Department of Natural Resources, or Environmental Protection Agency, except in regard to buildings used by the department or agency for its officers, employees, and equipment, and for capital improvements related to those buildings. Similarly, state agencies do not include the Illinois Housing Development Authority or Illinois Finance Authority.

Massachusetts

The Deferred Maintenance Program of the Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) is dedicated to preserving capital assets of state facilities.54, 55 The program, also known as critical repairs, was initiated about fifteen years ago and has undergone three significant changes to enhance reporting processes and efficiency in the use of resources.56 Initially, state agencies submitted annual deferred maintenance funding requests to DCAMM, which evaluated and prioritized the requests for submission to the governor and legislation for approval.

Due to limited funding—and to reduce wish list items—DCAMM revised the process. This change included state agencies’ submitting projects to their respective oversight body.57 These entities reviewed the requests and identified priority projects for consideration in the fiscal year. The overseers list of projects was then evaluated and prioritized by DCAMM and submitted to the governor and legislature for approval.

In 2019, DCAMM initiated a pilot program with the Executive Office of Education, the Department of Higher Education, and University of Massachusetts (UMass) Office of the President, to develop an effective process for making capital investment decisions for colleges and universities. This project aimed to address one of the common complaints to DCAMM from state agencies: not knowing the amount of funding they would receive over time.58 Currently, the state places a high priority on critical repairs and critical infrastructure. As of 2025, DCAMM has committed to provide a determined amount of funding every year under the critical repairs program for departments of corrections, sheriff’s offices, police, trial courts, health and human services, and the military.59 In addition, in terms of higher education, the capital plan prioritizes critical repairs and infrastructure and provides additional funding so that leaders can focus resources on programmatic priorities without compromising infrastructure needs.60, 61

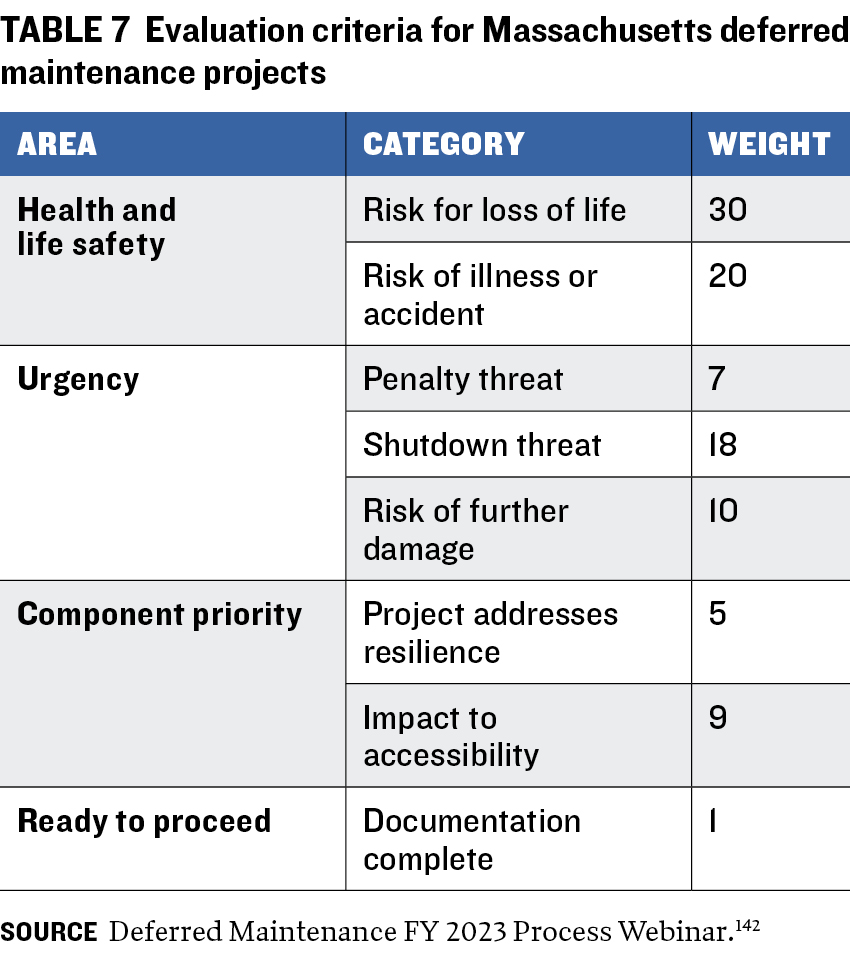

State agencies submit deferred maintenance funding requests to DCAMM each May62 through the Capital Asset Management Information System (CAMIS) database.63 These submissions are supported with documents and other information rationalizing requests.64 These include cost quotes, work orders, preventative maintenance records, and code violation documents, incident and accident reports, and photographs. Additionally, state agencies must provide details about the project, such as life safety risks, shutdown threats, further damage, potential penalties, resiliency, accessibility, age of the equipment, expected remaining life and repair costs in the last five years. This input increases the likelihood a project will get funding.

All deferred maintenance requests are compiled and submitted to the governor every year for approval and to be included in the five-year Capital Investment Plan.65 This plan is presented to the legislature to vote on bond bills to fund capital projects and programs, including the deferred maintenance program. These bills are reviewed by the Joint Committee on Bonding, Capital Expenditures, and State Assets and the respective Ways and Means committees before enactment by the House and Senate.

After funding is approved, state agencies are required to complete a certifiable study for each deferred maintenance project with an estimated construction cost (ECC) of $300,000 or higher.66 This study should follow DCAMM’s deferred maintenance study template67 and include an investigation of existing conditions, a summary of codes and regulations, options and proposed solutions, a cost estimate summary, proposed schedule, and appendices. The study must be performed by a so-called House Doctor and submitted to DCAMM for certification before an agency can receive funds for design and construction to proceed. House Doctors are licensed architects or engineers who can investigate a problem, identify options, offer solutions, and provide design services through the Designer Selection Board. A House Doctor can be a nondesign consultant with appropriate expertise or a qualified staff at the requesting agency.

Deferred maintenance projects with an ECC below $300,000 do not need a study. This threshold applies for all projects, regardless of the funding source, and even if the project has an emergency waiver. The certification of the study includes reviewing it for completeness and conformity with long-range capital plans, determining that sufficient funds are available for design and construction, and recommending it to the DCAMM commissioner for certification.

Additional requirements exist when the requesting agency manages a project.68 Deferred maintenance projects may be funded and managed in one of three ways:

DCAMM funds the project and transfers the money to the requesting agency, while the agency contracts for the study (if needed), solicits contractor bids, and manages the project.

The requesting agency funds the project, contracts for the study (if needed), solicits contractor bids, and manages the project.

DCAMM funds the project and contracts for the study (if needed), solicits contractor bids, and manages the project for the requesting agency.

For the first two approaches, the requesting agency must be granted delegation authority from DCAMM’s commissioner if the project has an ECC of $250,000 or greater. Additionally, for projects with an ECC of over $5 million ($10 million for UMass) and involving structural or mechanical work, DCAMM is responsible for the control and supervision of design and construction projects.

Once deferred maintenance projects are approved for funding, requesting agencies are required to submit a cash projection for the project on CAMIS and update it quarterly.69

Over time, making documentation available and providing proper training for state agencies has been key to the success of the deferred maintenance program.70 DCAMM makes instructional material, study templates, and webinars available through its website and ensures that these are regularly updated with the latest system changes. These resources are available for state agency staff to:

Guide submissions of deferred maintenance funding requests through CAMIS;

Enhance understanding of the prioritization process; and

Emphasize the importance of submitting complete information to ensure a comprehensive and efficient prioritization process.

These materials also outline the requirements necessary for funding disbursement.

Assets considered for the deferred maintenance program include state facilities. The term capital facility is defined in the General Laws (Part I, Title II, Chapter 7C § 1) as “a public improvement such as a building or other structure; a utility, fire protection, and other major system and facility; a power plant facility and appurtenances; a heating, ventilating, air conditioning or other system; initial equipment and furnishings for a new building or building added to or remodeled for some other use; a public parking facility; an airport or port facility; a recreational improvement such as a facility or development in a park or other recreational facility; or any other facility which, by statute or under standards as they may be prescribed from time to time by the commissioner of capital asset management and maintenance.”

The definition also provides that highway, transportation, and information technology improvements are not considered capital facilities. The deferred maintenance program addresses the capital repair needs of these facilities, including boiler repair or replacement; heating, ventilation, and air conditioning repairs or replacement; plumbing repair or replacement; exterior envelope repair (roofing, windows); interior repairs; fire alarm and security systems; electrical systems, elevator repairs or replacement; and accessibility improvements.71

DCAMM is responsible for facility planning, project delivery, property management, and real estate services for executive branch agencies, constitutional offices, the judiciary, and the state house.72 Entities under DCAMM authority include the Office of Administration and Finance, Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS), Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS), Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development, Secretary of State, Executive of Veterans Services, and Executive Office of the Trial Court (EOTC). DCAMM also collaborates with the Executive Office of Education, the Department of Higher Education and UMass, under a strategic framework for long-term capital investment decisions, including critical repairs.73

In addition to overseeing the Deferred Maintenance Program, DCAMM has occasionally performed a facility condition assessment (FCA) of state-owned buildings, facilities, and sites.74 In June 2019, DCAMM issued a request for proposal to conduct an FCA at a variety of state-owned buildings, including higher education facilities, general-purpose administrative and recreational facilities, hospitals, clinics, laboratories, and residential health care facilities under the EOHHS; public safety and correctional facilities under the EOPPS; and courthouses under the EOTC.75 By December 2022, the FCA was in progress for 259 state-owned buildings and grounds occupied by nine state universities and fifteen community colleges.76 These assessments would be made available to agencies for strategic planning and investment, thus reducing the deferred maintenance backlog. As of January 2025, DCAMM had not conducted FCAs for all facilities in the state.

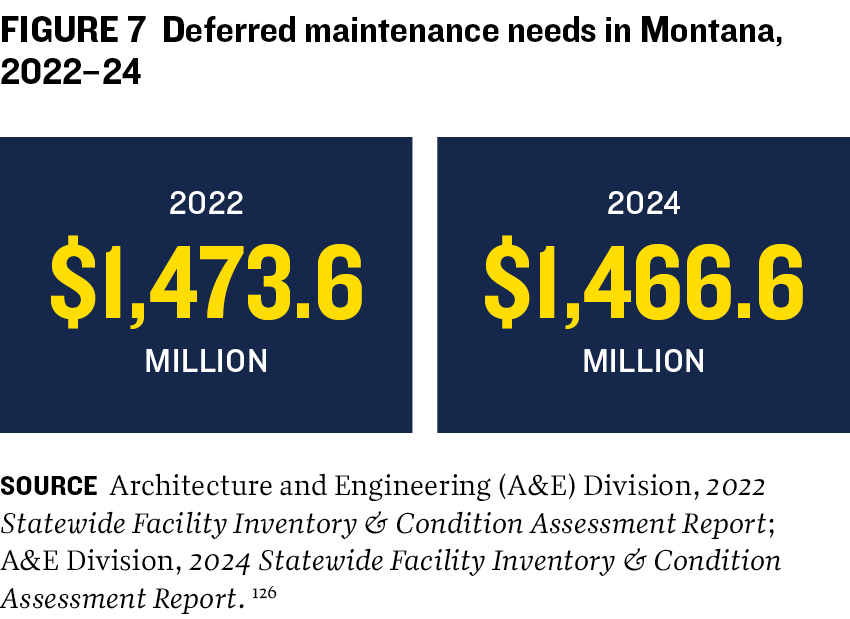

Montana

The Architecture and Engineering (A&E) Division is responsible for the facility inventory, oversees facility condition assessment (FCA), and manages the long-range building program (LRBP) major repair account.

To develop a statewide facility inventory following adoption of Senate Bill 43 in 2017, A&E used preexisting data from the Risk Management and Tort Defense (RMTD) Division of the Department of Administration.77 RMTD maintained the only central listing of state-owned facilities for insurance purposes. State agencies self-report facility details including the area, construction type, and location and update the information annually to ensure proper insurance coverage. Since 2017, A&E has maintained the facility inventory and receives the list of buildings from the RMTD database each year.

The current facility inventory is being adjusted to include a complete list of facilities and their information.78 The statewide facility inventory contains all state-owned facilities from the RMTD database, including state-owned buildings with a current replacement value (CRV) of $150,000 or less. Uninsured facilities are absent from the inventory. In addition, A&E is working with state agencies to record buildings that are not listed in the inventory. Location data for some buildings are inaccurate or incomplete, especially multibuilding campuses or remote locations managed by the Fish, Wildlife, and Parks or Transportation departments. A&E plans to geolocate all buildings over time using latitude and longitude coordinates.

Other information needing adjustment includes buildings’ CRV and eligibility for the long-range building program (LRBP).79 Currently, buildings’ assigned CRV may be different from their actual value. As state agencies do not assign a current replacement value to their buildings, Risk Management and Tort Defense determines an insured valuation. For buildings valued at less than $1 million, RMTD generates an insured current replacement value on a cost-per-square-foot basis. For buildings valued over $1 million, RMTD generates the insured CRV through an appraisal conducted about every five years.

The actual total project replacement cost is typically higher than the insurance-appraised CRV. In addition, the RMTD uses a factor (provided by their underwriters) to adjust each building’s CRV every year. Similarly, the LRBP-eligibility determination is made via a manual process whereby state agencies determine which of their buildings are LRBP-eligible according to the definition in Montana Code Ann. § 17-7-201.

LRBP-eligible buildings with a CRV over $150,000 require a periodic FCA.80 The assessment helps identify building deficiencies and provides a facility condition index (FCI), the deficiency ratio the state uses. The FCI is a calculation that compares the costs of deferred maintenance to a building’s replacement value and is defined as follows:

FCI = (Renewal needs and deferred maintenance/Current replacement value) x 100

FCI values under 5 percent are considered “good,” 5–10 percent “fair,” 10-30 percent “poor,” and over 30 percent “critical.”

A&E aims to assess each facility once every four years (A&E Division, 2024, Montana Code Ann. § 17-7-202). The industry standard is to conduct building assessments every three to five years, and A&E decided on a year in the middle, as it aligns with two rounds of the budget cycle and provides ample time for decision-making between assessments. A&E also acknowledges that achieving this goal is a challenge because of the size of the inventory and the limited number of assessors. In August 2024, 562 of the 1,050 LRPB-eligible buildings required an FCA.

While A&E initially conducts baseline facility assessments for all state agencies, the agencies are responsible afterward for maintaining accurate facility data and incorporating data into daily operations.81 Given that some agencies may lack the staff expertise and time to conduct facility evaluations, the division requested $1.5 million for the LRBP project to conduct baseline assessments for all of them. An architecture firm will perform those, ensuring consistency and a lack of bias. The assessments were scheduled to be completed by the fall of 2025.82

A&E also plans to conduct training to ensure consistency in future assessments.83 State agencies with qualified staff will probably manage their own assessments, while agencies without such resources will have a consultant or an A&E staff member assigned to conduct them. This will ensure that all state-owned facilities are accurately evaluated and documented within the system.

A&E uses Archibus,84 a commercially available property and inventory management system. The goal is to use the tool for data collection, analysis, and management across all state agencies and help reduce long-term maintenance costs.

In its assessments, Montana defines “buildings” as facilities or structures constructed or purchased wholly or in part with state money, located at a state institution, or owned (or to be purchased) by a state agency, including the Department of Transportation (Montana Code Ann. § 17-7-201-1). The term does not include buildings, facilities, or structures owned by a county, city, town, school district, or special improvement district, or a facility or structure used as a component part of a highway or water conservation project.

An LRBP-eligible building is defined in Montana Code Ann. § 17-7-201-6 as a, facility, or structure eligible for major repair account funding that:

Is owned or fully operated by a state agency and whose operation and maintenance are funded with resources from the state general fund; or

Supports academic missions of the Montana University System (MUS) and whose operation and maintenance are funded with current unrestricted university funds.

The term excludes buildings, facilities, or structures owned or operated by a state agency and whose operation and maintenance are entirely funded with state special revenue, federal special revenue, or proprietary funds, or that support nonacademic functions of the university system and whose operation and maintenance are funded by nonstate and nontuition sources.

All state departments, agencies, and institutions, including the university system, are involved in the deferred maintenance assessment.85

State agencies fund major repair and capital development projects through the LRBP.86 Deferred maintenance projects are part of this program. State agencies submit their request by July 1 of the year preceding a legislative session using the LRBP submission portal. After that, A&E works with the Office of Budget and Program Planning (OBPP) to review and evaluate project requests for feasibility, agency needs, and changes in operating costs. These requests are compiled in a single list of prioritized statewide projects and submitted for review to the governor, who submits the requests in a comprehensive long-range proposed building program as part of the executive budget. A&E is also required to provide a facility inventory, condition assessment, and calculation of the deferred maintenance backlog to the OBPP and the Legislative Finance Committee to inform decision-making.

Oklahoma

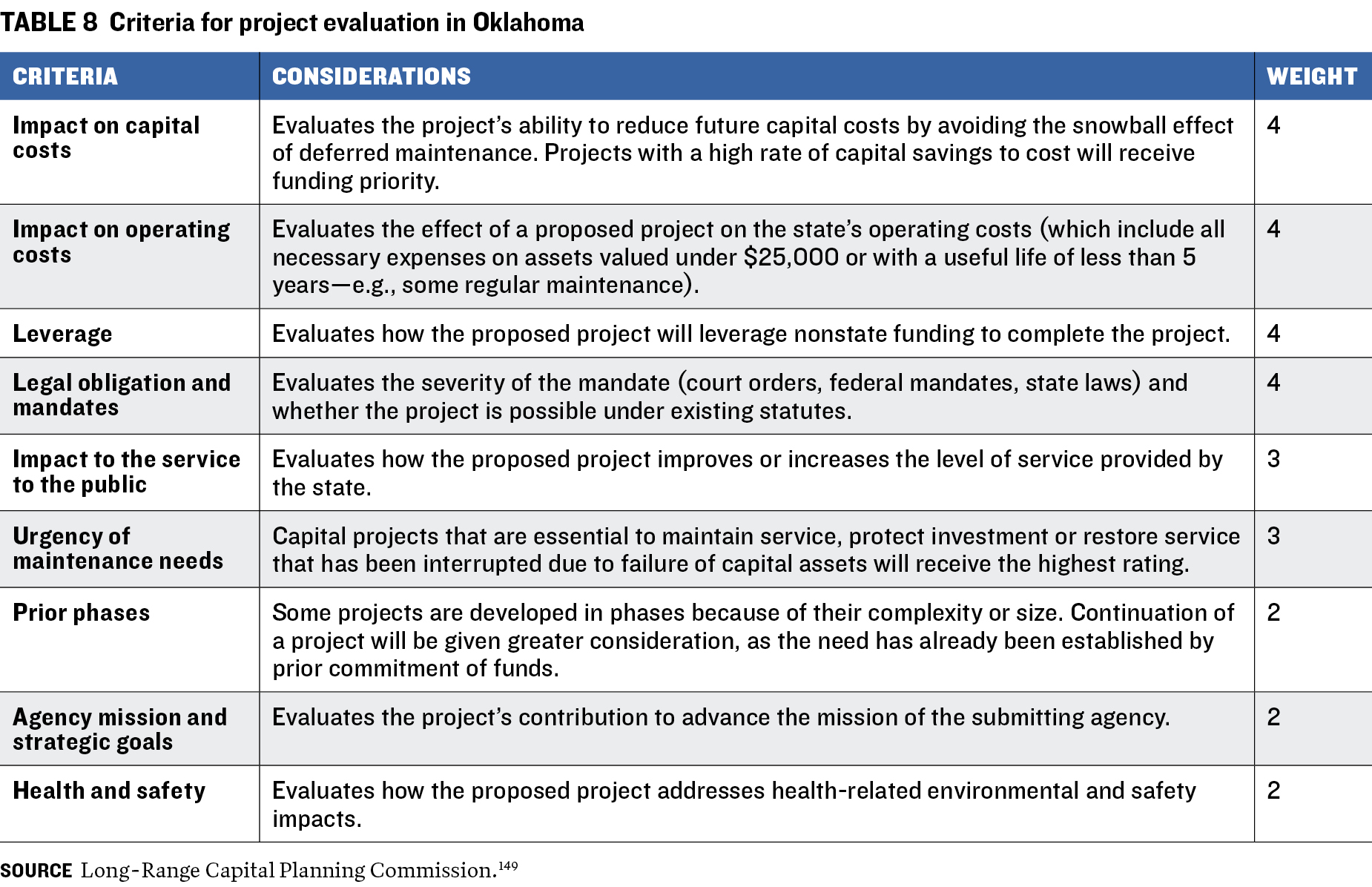

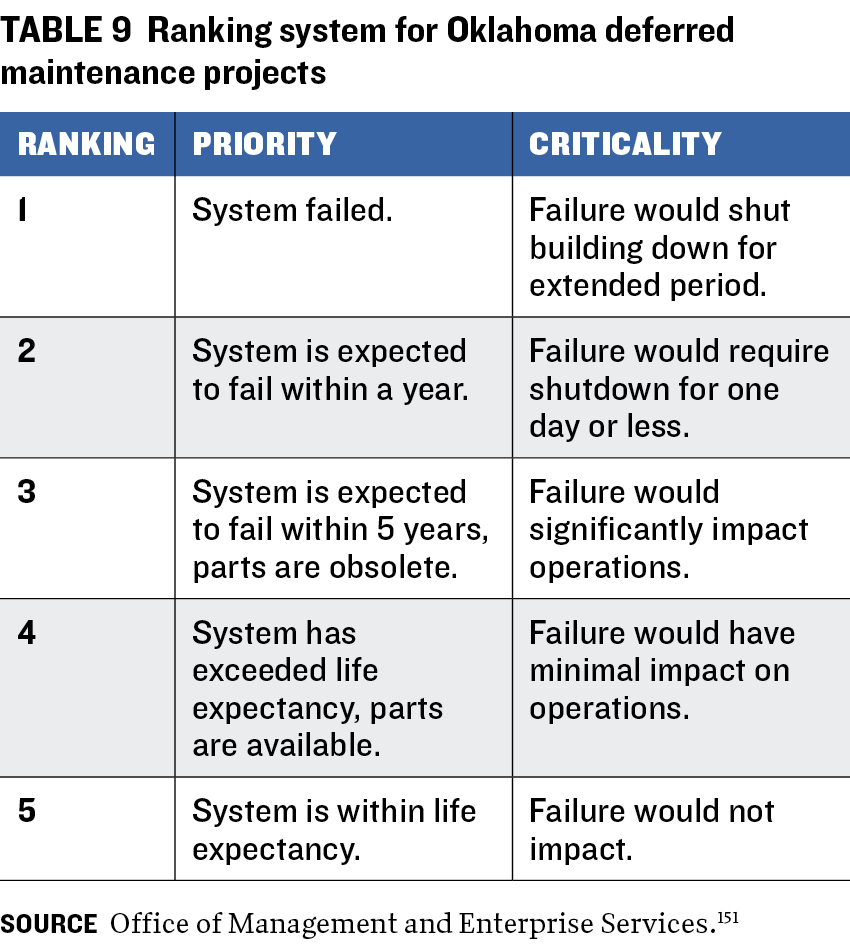

As part of Senate Bill 1052, the Division of Capital Assets Management (DCAM) issued a capital planning and asset management report in 2012 recommending a course of action for the streamlining, integration, and consolidation of state construction, maintenance, and management.87 One of the recommendations was that each agency develop a three-component budget comprising operations and maintenance, capital improvement (including deferred maintenance), and capital development. The capital improvement component covers major deferred maintenance, equipment replacement, and restoration or minor renovation costing between $50,000 and $2.5 million. In addition, such components should be developed using data collected during assessment, life-cycle analysis, and master planning. The initial recommendation was for capital investment planning to have a five-year time span, but an eight-year period was selected.

Another recommendation was to standardize the planning methodology into several phases.88 Following are aspects of the first four phases relevant to assessing and budgeting for deferred maintenance needs:

Phase 1—ORGANIZE: Gather information required by House Bill 2392,89 including a comprehensive inventory of capital facilities; estimates of mandatory, essential, desirable, and deferrable repair, replacement, and expansions; and recommendations on the maintenance of physical properties and equipment of state agencies. The Office of Management and Enterprise Services (OMES) is required by the Oklahoma State Government Asset Reduction and Cost Savings Program (Okla. Stat. § 62-908) to publish an annual report containing an inventory of all state-owned property. This inventory includes buildings and other structures, as well as land and mineral assets. In addition, OMES is required to list the five percent most underused state-owned properties. Findings from the State Government Asset Reduction and Cost Savings Program must be included in capital planning according to the State Capital Improvement Planning Act (Okla, Stat. § 62-901).

Phase 2—ASSESS: Create a baseline for the facility condition index (FCI), analyze and synthesize data, establish reporting methodologies, and determining the FCI and fit for use conditions. The outcome of this phase is the creation of a facility condition assessment and life-cycle cost analysis (LCCA) for each state building.

Phase 3—DEVELOP THE PLAN: The plan Includes ranking projects according to the scoring metrics (described in the Prioritization of Deferred Maintenance section of this report).

Phase 4—IMPLEMENT: Develop pilot Capital Facility Plans for selected small, medium, and large state agencies and submission of capital improvement and capital development projects to the Long-Range Capital Planning Commission (LRCPC).90